The Remarkable Rebirth of the Button Accordion

Musician Gilberto Reyes redesigned the instrument to meet the needs of Latino musicians

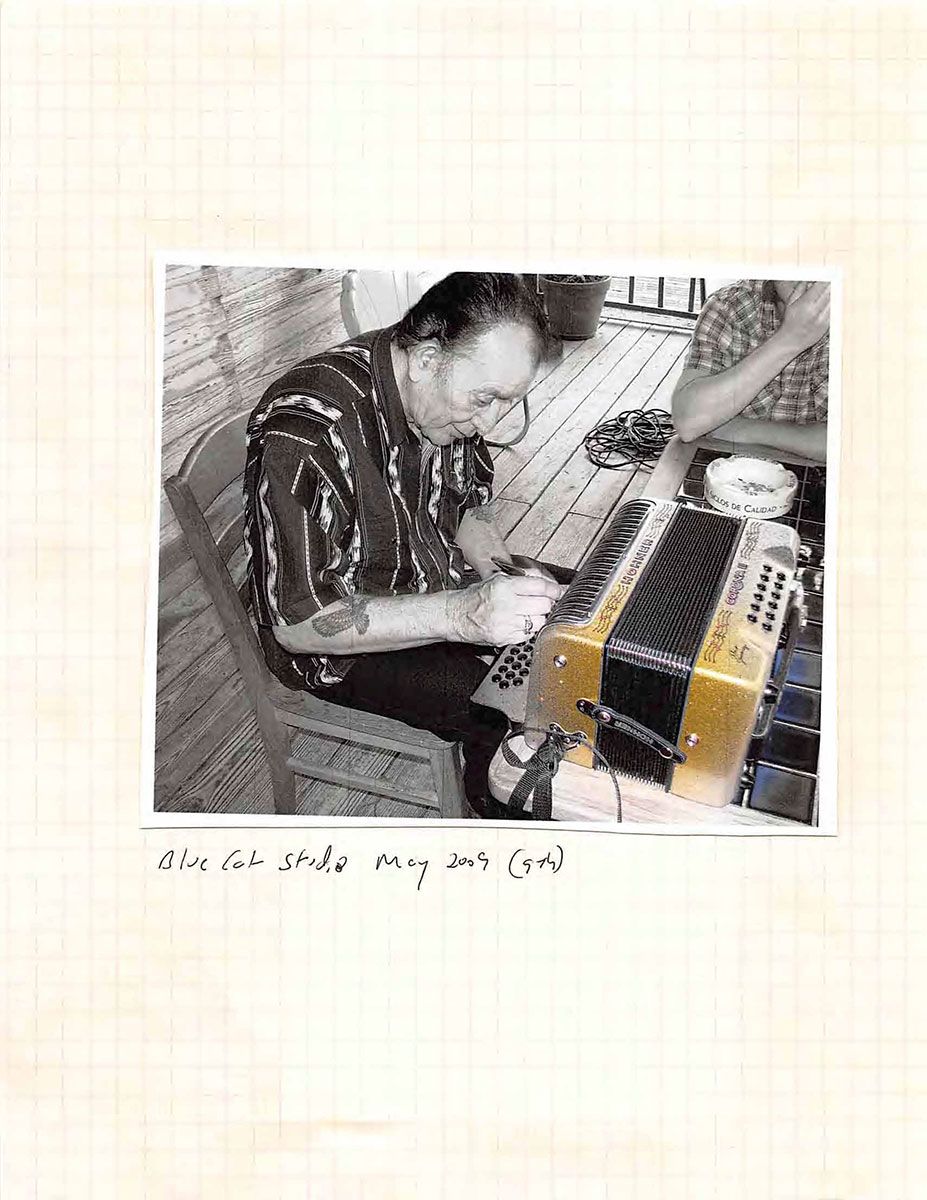

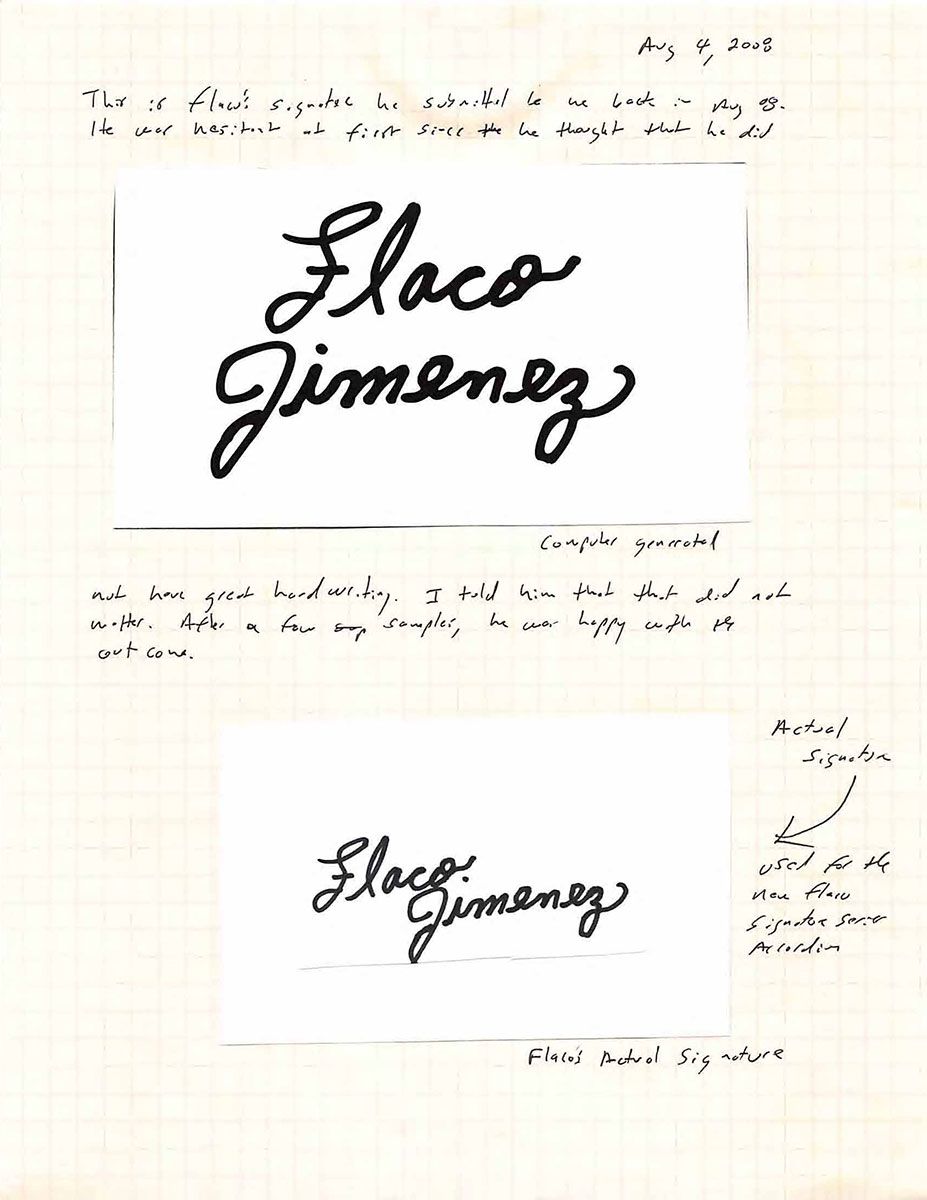

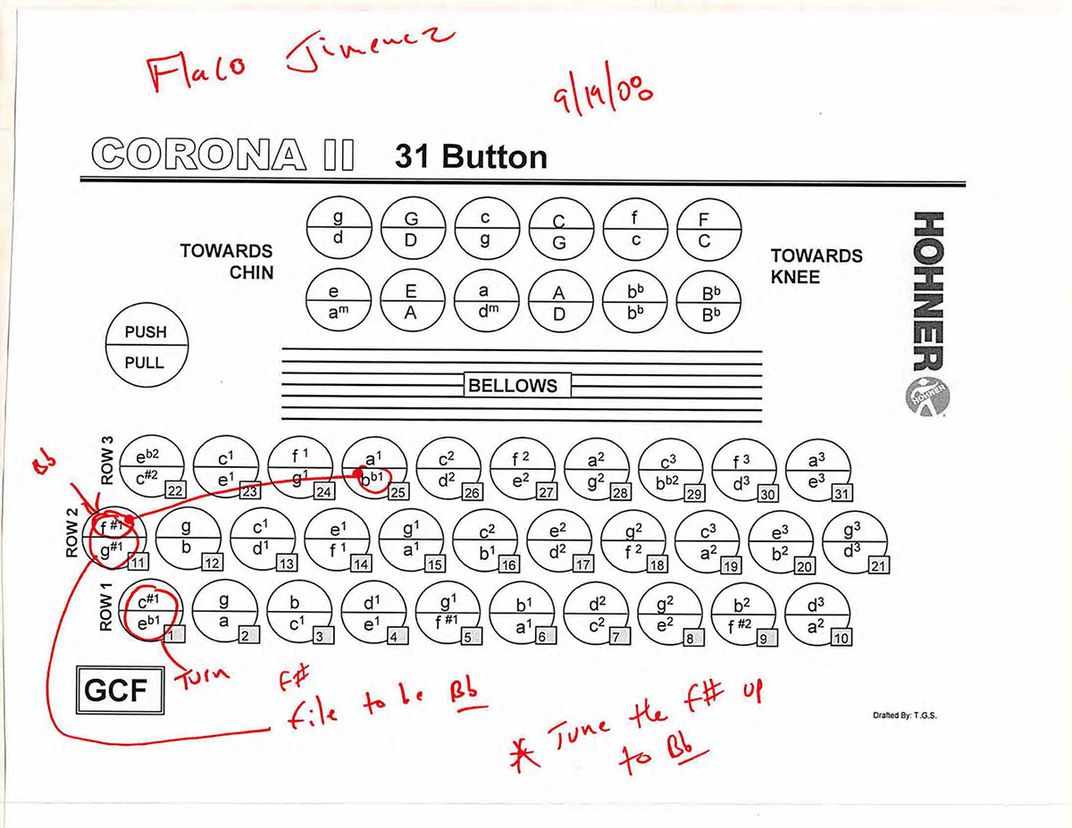

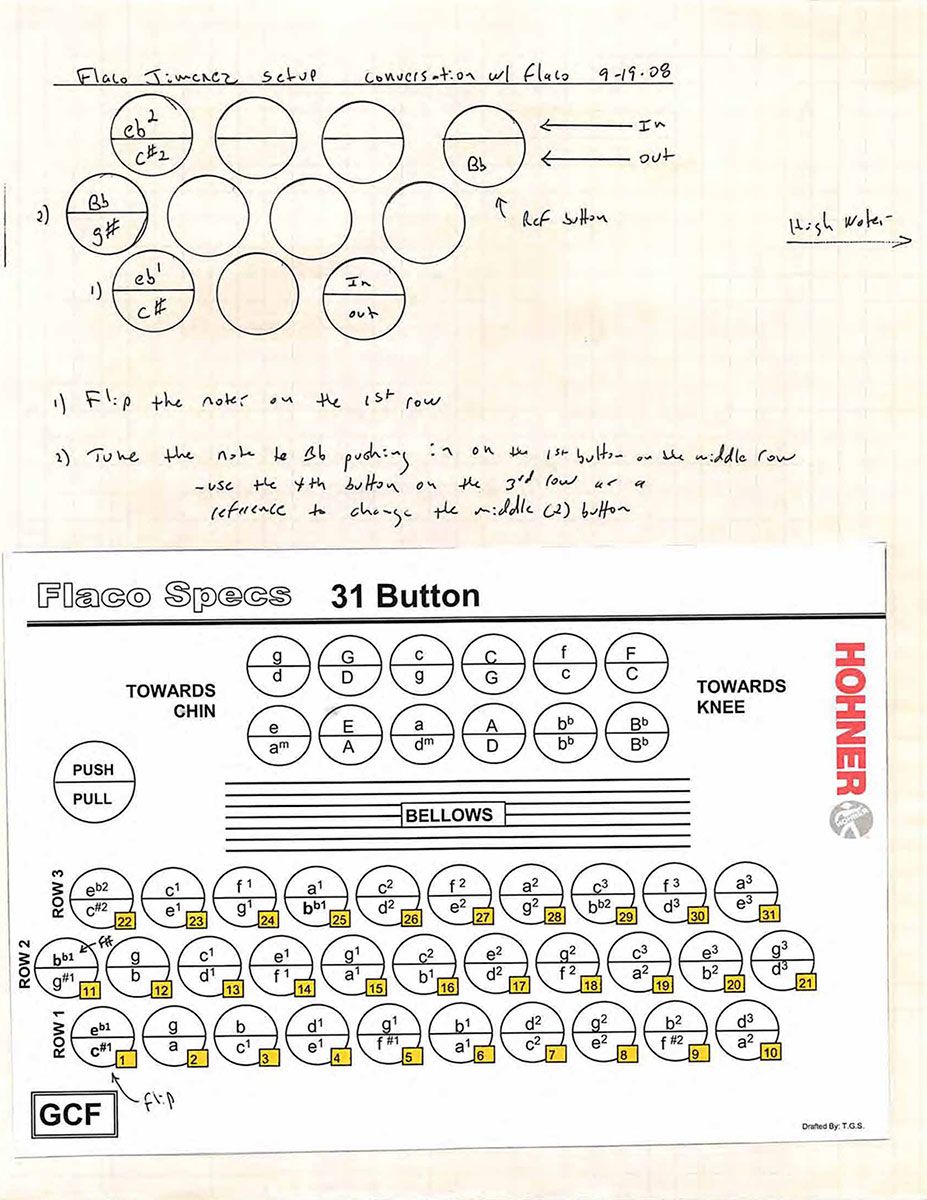

Musician and accordion designer Gilberto Reyes met us at the door of Hohner’s national headquarters then located in historic Glen Allen, Virginia. He and I had many mutual friends but had never met in person. I had learned that Reyes was a devoted follower of accordion legend Flaco Jiménez and that he had recently spent several days with Jiménez, taking extensive field notes, photos and sketches of accordion parts, with the intention of creating a new Corona II Classic Flaco Jiménez model accordion for Hohner’s Signature Series.

“He’s such a hero of mine, and to work with him on this project was amazing,” says Reyes. I was a Flaco fan, too, and had recently produced an album for Smithsonian Folkways with Jiménez and the brilliant bajo sexto innovator Max Baca, entitled Flaco & Max: Legends and Legacies, so we had lots of stories to share.

Reyes calls Flaco Jiménez the B.B. King of Texas Mexican accordion music: “I’ve been listening to him since I was a kid. My grandfather was a big fan as well. I have all his collection of LPs and 45s,” he told me. Reyes had graciously arranged to donate one of Flaco Jiménez’s accordions to the National Museum of American History, so museum curator Margaret Salazar-Porzio and Folklife media director Charlie Weber teamed up with me to interview him about Jiménez’s significance in American culture, the accordion that would mark Jiménez’s role in history, and Reyes’s own influential work with Hohner.

Gilberto Reyes was one of the most influential, modest and under-recognized people in American regional and Mexican traditional music. At Hohner, a German company founded in 1857, he was one of five product managers, each assigned to certain musical instruments. He oversees all of Hohner’s accordion products and has been at the forefront of a resurgence of accordion music, especially the button accordion favored by Mexican and Mexican American musicians. To me, he was a cultural advocate and music game changer of the first order.

“We came from very humble beginnings, working in the cotton fields,” he recalls. “That’s where it originated.”

Reyes grew up in the heart of the Texas Rio Grande Valley, born in Harlingen in 1961 and raised in Weslaco. His parents were from General Terán, Nuevo León, on the Mexican side of the border, but they eventually settled on the Texas side. Both his grandfather and his father played the two-row button accordion as a pastime and as part-time professionals.

He remembers how rural border life shaped both him and the music we today call conjunto: while neither his father nor grandfather were widely known as musicians, they were friends with musicians now considered to be among the most notable names in Tejano (Texas Mexican) music―accordion pioneer Narciso Martínez, Los Alegres de Terán, Los Donneños (named after Donna, Texas), Tony De La Rosa, Valerio Longoria and many others.

As a young boy, Reyes had little idea of the cultural importance of these musicians. He knew Narciso Martínez, for example, as a zookeeper, his day job. In 1975, he met Arhoolie Records founder Chris Strachwitz, who was in the valley to film the milestone documentary on Texas conjunto music, Chulas Fronteras. As a young boy, all Reyes realized at the time, though, was that his father had killed a steer for the barbecue that was the center of the party documented by the filmmakers.

Reyes loved his family’s music. He was intrigued by his grandfather playing in cantinas on the weekends, and he learned to play guitar, bass and accordion. His father, though, encouraged him to go to college. He did and eventually moved to Sacramento, California, where he worked for Wells Fargo and Lt. Governor Leo McCarthy.

However, he never left his music. He formed a conjunto of his own, started a web forum for button accordion players, repaired and tuned accordions, and tinkered with innovations to his 31-button instrument. He added three buttons, extending the upper range of the instrument—and attracted the attention of the Hohner company. They made a prototype and then in 2008 invited him to work with them. It was an emotion-packed experience, and he could not help but wonder how proud his grandfather might have been to know that he was a key player in the company that made his accordions.

“Never in my wildest dreams would I have imagined that I would be working for Hohner, and creating new products, and working with all these artists that I am working with now,” he says. “It hit me in 2009 when I went to Germany. I went to Matthias Hohner’s grave, and I saw all the tombstones of all the Hohners there. I’m like, ‘I just can’t believe that I’m here, in Trossingen, Germany, at the tomb of the founder!’ I had to sit down, because I felt so overwhelmed,” he says.

But at the beginning, prospects were grim.

“When I got [to] Hohner, the accordion business was dead. We had maybe two models that were doing well, and that was it. We didn’t have any of the artists working with us. We were in a recession, and a lot of people were saying, you’re going to work for Hohner and try to sell accordions, but nobody’s going to buy them because they’re all going back to Mexico,” he says. “But we were observing the opposite. All of a sudden, North Carolina—huge increases in Latino population. Increases in Maryland, increases in New York, places where you never thought of. Typically, it was California, Texas, Florida.”

Reyes put his accordion knowledge, cultural background and business acumen to work, turning around the accordion’s popularity. In the 1940s and 1950s, the piano accordion (with piano-style keys) had been king, and the company wanted him to bring the instrument’s popularity back.

But Reyes saw that the future lay in both the button accordion and the burgeoning Latino community.

After crafting a business plan, he went straight to the artists for advice, strengthening ties to the community and bringing artists’ ideas, preferences, and innovations to the fore. He honored artists such as Jorge Hernández and Eduardo Hernández of Los Tigres del Norte and many others. And he remembered how the music of fellow Tejano Flaco Jiménez really touched him.

“It was something about his music,” Reyes said. “It was alegre (lively). It was different. I don’t know how to explain. It spoke to me.”

When Reyes had the chance to ask Jiménez about what he thought was special about his accordion playing, he remembers Flaco saying, “Every note―every single note―I feel it with my heart. I want to cry. When I press that button and that sound comes, it gives me some interesting emotion, and I don’t know how to explain it. The only thing I can explain is, I want to cry.”

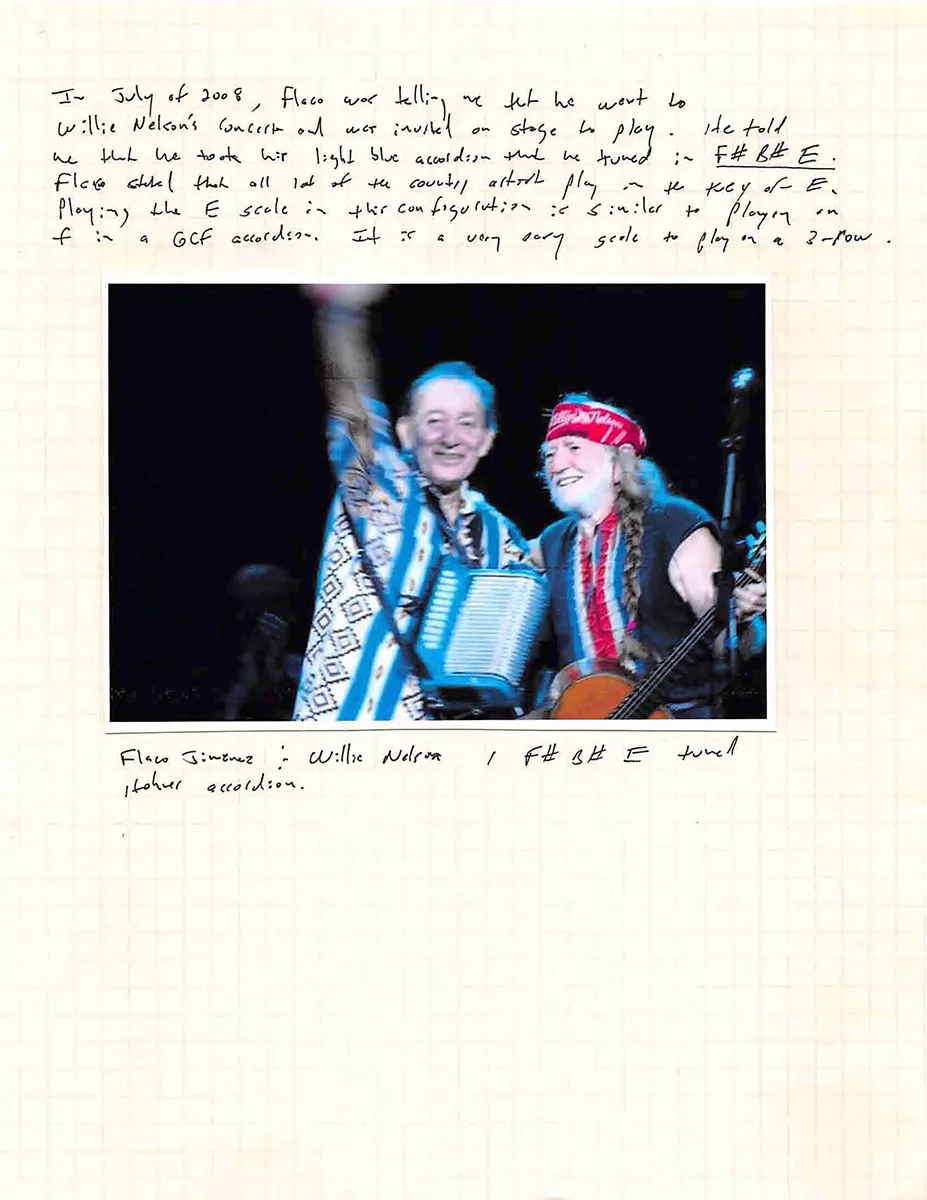

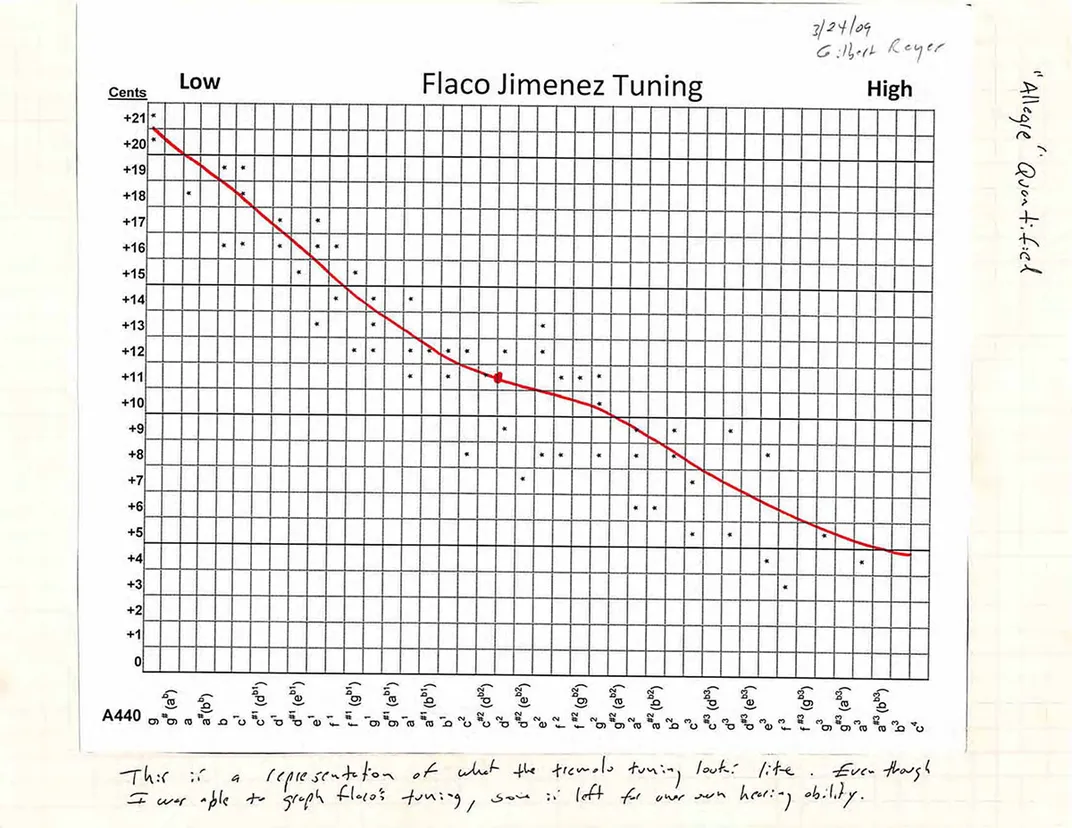

Finally, there is nothing more important than the sound of the accordion. Reyes, with his deep, first-hand knowledge of how the accordion works, knew that within the button accordion world, there were distinctive niches of sound, especially the Mexican norteño sound and the Texan conjunto sound. The main differences lay in the tonality of the reed. Mexican norteño musicians prefer a “wetter” sound, with more vibrato. Texan musicians favor a “drier” sound, with less vibrato. Tejano accordionists also tend to individualize their accordions more.

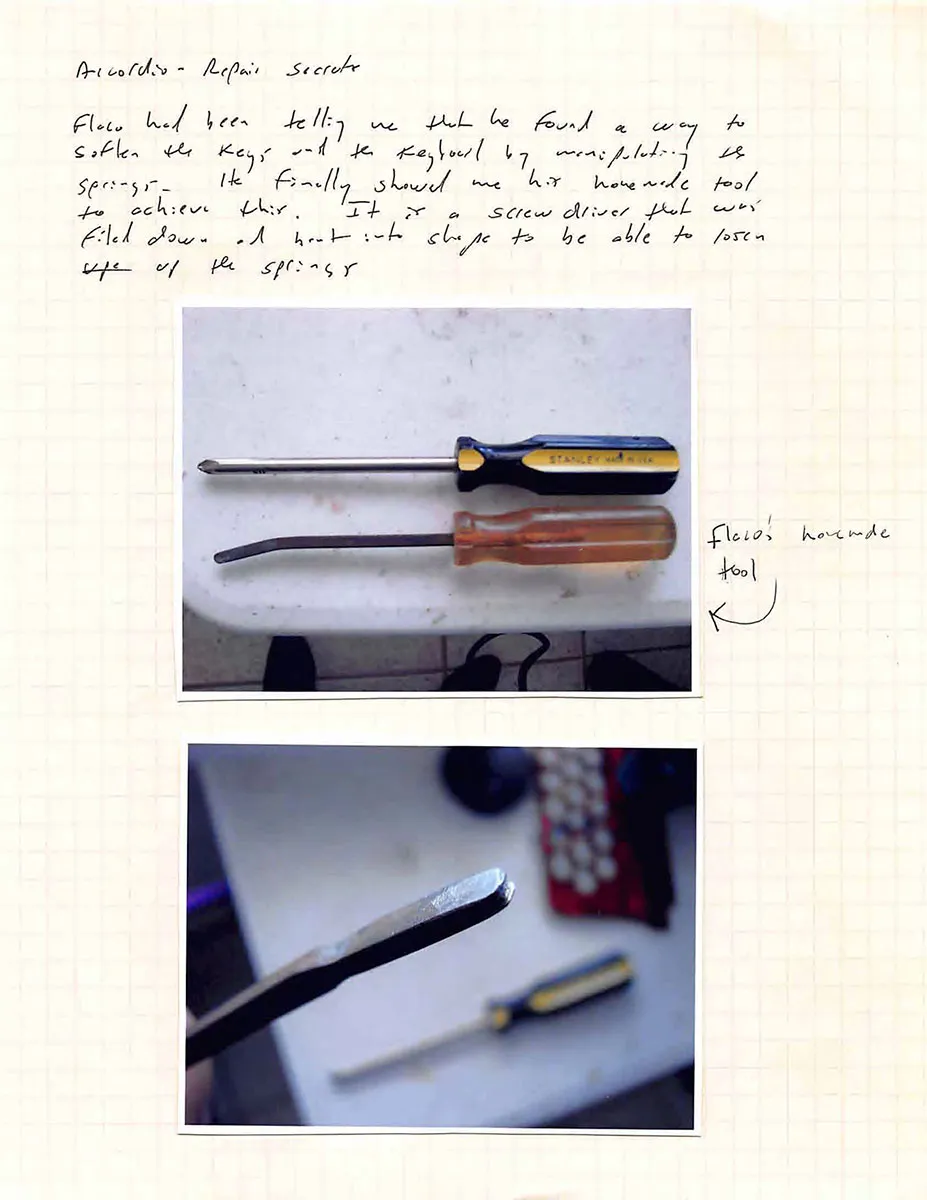

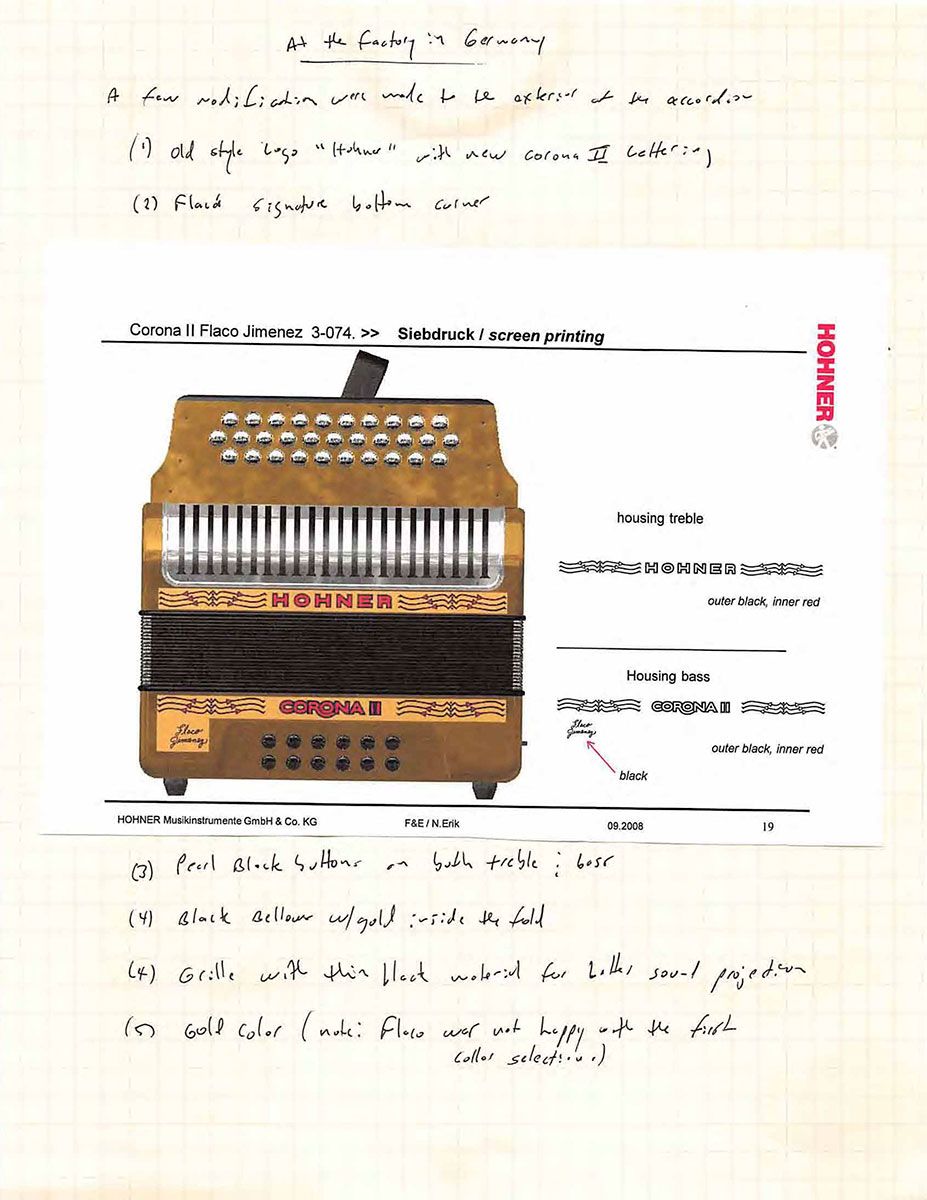

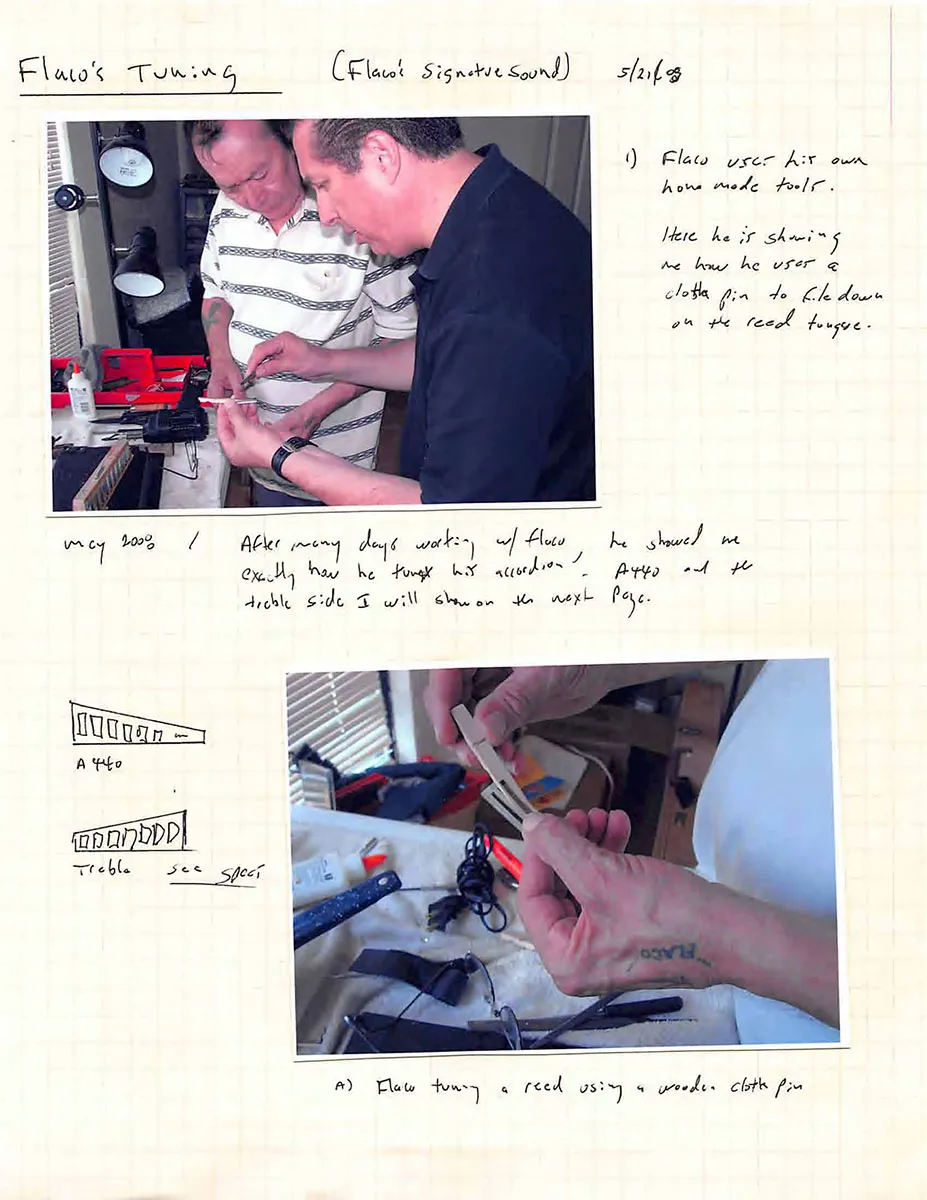

How do you create these different shades of sound? It is mainly through “tuning” the metal reeds that vibrate to produce the sound. For example, Reyes learned Jiménez’s technique of adding a small drop of lead to a reed to change its pitch ever so slightly, creating a special tremolo vibrato effect. He analyzed and diagramed the technique, sent it to the factory experts, and created a new line of accordions with the Flaco Jiménez signature sound.

Under Reyes’s guidance, accordion sales increased sharply.

“Over a thousand accordions every month go out from here into the market,” he reports. “Sometimes it’s close to 2,000.”

Reyes’ way of working closely with Mexican and Mexican American accordion culture bearers brought Hohner into much closer sync with musicians and community members alike. He developed lower-priced but good quality instruments to help bring more low-income young people to the music.

While he is relatively invisible to the public, Reyes has had major cultural impact. He evokes Jiménez’s words when he describes seeing a young person with an instrument he developed.

“It’s Flaco saying: ‘Every note that you touch, it makes you want to cry.’ That’s how I feel when I see some kid playing an accordion that I designed. I become emotional. ‘Wow, I had a part in that,’ I tell myself. I still can’t believe I’m doing this. It’s not earth-shattering, but to me, because of where I come from, it is.”

Daniel Sheehy is curator and director emeritus of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

A version of this article previously appeared on the online magazine of the Smithsonian Center for for Folklife and Cultural Heritage

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Daniel_Sheehy_headshot.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Daniel_Sheehy_headshot.jpg)