Remembering Dave Brubeck, Goodwill Ambassador

Joann Stevens remembers legendary jazz artist Dave Brubeck, who died Wednesday at age 91

![]()

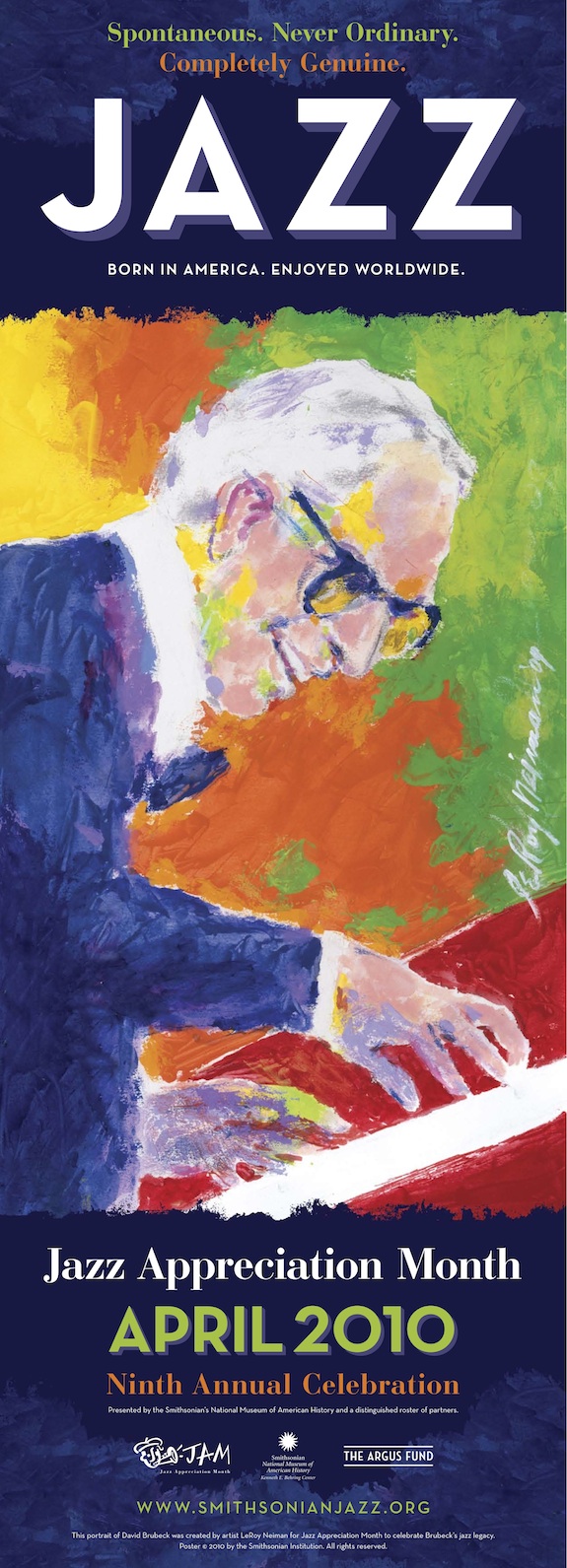

This 2010 poster was created by LeRoy Neiman as a tribute to Dave Brubeck, a 2009 Kennedy Center Honoree. Courtesy of the American History Museum

Guest blogger, Joann Stevens is the program manager of Jazz Appreciation Month at the American History Museum. Courtesy of the author

Dave Brubeck, who died Wednesday at age 91, was a quintessential jazz artist of the 20th and 21st centuries. He didn’t just perform music, he embodied it, taking us to outer stratospheres with compositions like Take Five included in “Time Out,” the first jazz album to sell a million copies. Tributes are sure to highlight Brubeck’s tours, music milestones, awards, complex rhythms and honors like making the cover of Time magazine in 1954.

I’ve loved Brubeck’s music since hearing Take Five at age 10. But it was only after joining the Smithsonian’s Jazz Appreciation Month (JAM) initiative in 2008 that I met him, saw him perform live and experienced his lifelong commitment to social justice and unity in the U.S. and worldwide. Brubeck said “freedom and inclusion” were core principles of jazz. This was a creed he lived by and the legacy he leaves. The National Museum of American History has supported that legacy in its JAM programming. These are some of the remembrances that I wish to share of our relationship with Dave Brubeck, Goodwill Ambassador of music around the world.

Every year, JAM creates a jazz poster that is distributed, free worldwide with help from the U.S. State Department, the Department of Education and other collaborators. When the then 88-year-old artist LeRoy Neiman learned that Brubeck was to be a 2009 Kennedy Center honoree, he created a playful portrait of a white-haired Brubeck as elder statesmen, in recognition of his lifetime achievements. That lasting image became a grace note to American jazz, and was distributed to every U.S. middle school, to every U.S. embassy, to 70,000 music educators and to some 200,000 people, worldwide, who wrote us and requested copies. A framed copy, autographed by Brubeck, hangs in the museum director’s office. Brubeck’s message reads “Jazz Lives! Keep Playing!”

At a White House reception for the 2009 Kennedy Center honorees, President Barack Obama introduced Brubeck with these words: “You can’t understand America without understanding jazz. And you can’t understand jazz without understanding Dave Brubeck.” The president shared a cherished childhood memory.

The President then recalled the few precious days he’d spent with his absentee father: “One of the things he did was to take me to my first jazz concert.” That was 1971, in Honolulu. “It was a Dave Brubeck concert and I’ve been a jazz fan ever since.”

Brubeck pictured circa 1960. Photo by Associated Booking Corp., Joe Glaser, President, New York, Chicago, Hollywood. Courtesy of the American History Museum

First concert, a concept that introduces children to jazz, is carried on today by an elite corps of jazz students, selected annually, for the Brubeck Institute Jazz Quintet. They have performed regularly at the Smithsonian’s free JAM music programs. But even free can be costly to schools serving low income, immigrant neighborhoods, where travel budgets are small or non-existent. Unable to bear the travel expense, an area elementary school music teacher asked JAM’s help to deliver jazz programming to the classroom instead. The Quintet and Brubeck program leaders responded, first holding chat sessions and then playing two sets for 800 students and invited area teachers. The air was electric with the joy of children, most of them immigrants from Africa, Latin America and the Middle East, hearing Blue Rondo A La Turk and other Brubeck tunes. Later the children created art and poetry about the band and how the music made them feel. The arc of Brubeck’s Jazz legacy was in full swing that day. Teachers marveled at the Quintet’s performance, admitting ”we didn’t think they’d be that good.”

April 2008 marked the 50th anniversary of Dave Brubeck’s State Department Tour as the first U.S. jazz musician to perform behind The Iron Curtain. Meridian International, a JAM collaborator, presented a series of panel discussions and concerts. Jam sessions, a traveling exhibition, featured images of Brubeck, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and other jazz legends from the Archives Center’s jazz collections. John Hasse, curator of American music, joined Brubeck and others on the program.

“Dave Brubeck was a pioneer and brillant master of jazz cultural diplomacy,” Hasse said. “Serving on a program with him was a privilege I shall always cherish.”

Especially poignant during the anniversary was to have Brubeck at the Smithsonian for an onstage oral history. He talked candidly about his life, music and vision for a united humanity. He recalled the days of Jim Crow when tours with an integrated band proved challenging in the U.S. and abroad. Still, Brubeck rarely backed down about having African American bassist Eugene Wright in the band. He faced many challenges with a courageous, wry humor.

In the early 1960s, just before Brubeck was to perform before a crowd of boisterous students in a college gymnasium in the south, the school’s president told the band it couldn’t perform with Wright on the stage. The band packed up to leave. With the crowd cheering impatiently for Brubeck to perform, the administrator and the state governor, who had been called, caved on the condition that Wright take a place in the shadows at the back of the stage. With a firm grace, Brubeck placed a standing mic next to his piano and told his bassist ”Your microphone is broken. Use this one.” With Wright at center stage, the band performed to an exuberant, capacity crowd.

A friendship with jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong produced a collaboration with Brubeck and his wife, Iola, that created the Real Ambassadors, a cutting-edge, jazz musical that faced the nation’s race issues with lyrics like those in the song They Say I Look Like God, that had Armstrong sing: “If both are made in the image of thee, could thou perchance a zebra be?”

A concert in South Africa with Brubeck and his sons was mired by the shadow of death threats that the musicians received, if the integrated band performed.

“What did you do?” the interviewer asked.

Flashing his characteristic toothy grin, Brubeck said he told his sons. ”Spread out on stage. They can’t get us all.”

Joann Stevens is program manager of Jazz Appreciation Month (JAM), an initiative to advance appreciation and recognition of jazz as America’s original music, a global cultural treasure. JAM is celebrated in every state in the U.S. and the District of Columbia and some 40 countries every April. Recent posts include Playlist: Eight Tracks to Get Your Holiday Groove On and Danilo Pérez: Creator of Musical Guardians of Peace.