How a New Show Tears Down the Myths of Asian American History

Series producer Renee Tajima-Peña says the program is about “how we got where we are and where are we going next”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/a6/45a6da44-7e58-4255-9df9-cfd455618ecb/renee-tajima-headshot-no-mas-bebes.jpg)

For filmmaker Renee Tajima-Peña, telling the 170 years of Asian American history in the short, few hours of her new documentary series "Asian Americans" on PBS was a nearly impossible task. The population, which hails from geographic regions as diverse as the Indian subcontinent, southeast Asia, Japan and the Pacific islands, is no monolithic minority, despite what boxes may be checked on official forms.

As series producer of the five-part series that streams on PBS channels through June, Tajima-Peña tackles the broad-ranging group from many angles. Throughout the series, she tears down the myth of Asian Americans as a so-called “model minority,” among other stereotypes, and builds up their long history of cross-cultural relations with other disadvantaged ethnic groups.

Tajima-Peña’s previous work has investigated discrimination against immigrant communities and she was nominated for an Academy Award for her documentary Who Killed Vincent Chin?, which examined the murder of a Chinese American engineer by two white men in 1982 Detroit. Chin’s death and the resulting court case galvanized the Asian American community and still remains a flashpoint in Asian American political activism.

She spoke with Theodore Gonzalves, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, who is currently at work on an exhibit about the pioneering Filipina rocker June Millington. Their interview was edited for length and clarity.

The series doesn’t start with Chinese or Japanese laborers on the massive plantations of Hawaiʻi or in the gold mines of California’s Sierra Nevada foothills. These are the places traditionally thought of as launch points for Asian American history. Instead, you begin in St. Louis, Missouri, at the 1904 World’s Fair.

When we consulted with Asian American historians and explored the way they have been theorizing and looking at the Asian American story, it made sense to start with the legacy of U.S. empire in the Philippines.

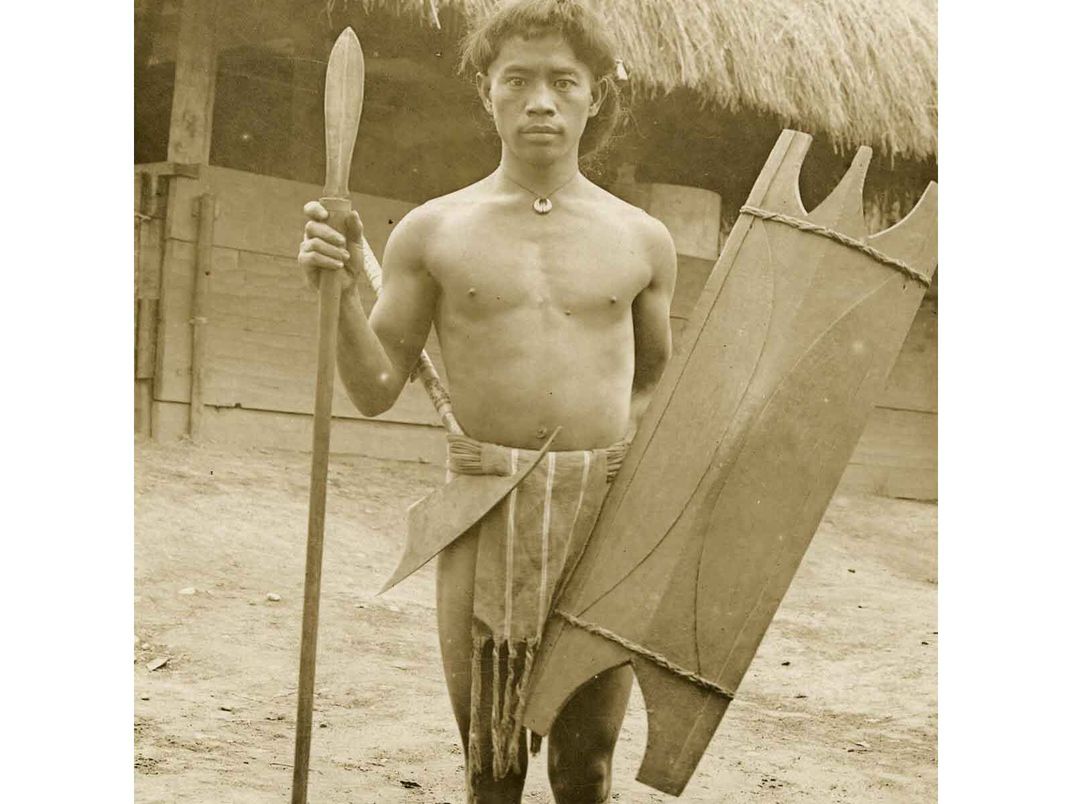

Starting at the beginning of time is not the most engaging way to start. Even if we just looked at 100 years of history, it would be massive. [Ken Burns’] “Country Music” got 13 hours on television, we had five hours to tell a story that spans over 170 years. For many reasons, the story of Filipino orphan Antero Cabrera (who was put on view in a replica village at the World’s Fair) made sense. It’s the story of empire. It establishes the idea of racial hierarchy and racial science and how that shaped the construction of race during the early 1900s. We thought that was fundamental not only to that episode, but to the whole history.

We wanted to shift the narrative of Asian Americans because outside of Asian American studies, I think most American people think the story starts when many arrive after the 1960s.

The second thing we wanted to challenge is this deeply embedded idea that [Asian Americans] are a model minority. And I think there was an assumption that, if you take the Irish American story or German American story and just, paint Asian faces on it, it would be the same story. And that's not true because of the marker of race. That’s never been true. We want to shift that perception of who Asian Americans are.

Civil Rights Movement activist John Lewis talks often about getting into “good trouble,” when he and others engaged in acts of civil disobedience. Could you talk about the idea that, despite the myth of Asian Americans as model minorities, there is a deep and ongoing tradition of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders as being trouble-makers?

There could be a whole film about Asian American labor movement activism. Stanford historian Gordon Chang has told us in his interview that in the 1860s, the biggest labor strike in the United States was mounted by Chinese immigrant railroad workers. In 1903, you have the Japanese and Mexican laborers striking together in Oxnard, or what’s remembered as the Great Sugar Strike of 1946 in Hawaiʻi, or in legal cases like Wong Kim Ark decided in 1898, guaranteeing birthright citizenship. Asian Americans have a long tradition of fighting for their rights in the fields, on campuses, in the courts and in the streets. You’re right: Despite these histories, there has persisted the narrative that AAPIs are compliant—for example, Japanese Americans “going to the camps like sheep.” But there are many examples of critical masses of Asian Americans who have moved U.S. history forward. And so we’re telling those stories.

This series also represents a return to the brutal murder of Vincent Chin. What does that mean for you as a public history documentarian to go back to this kind of material and to get a chance to retell it again?

I’m glad the team convinced me that we should tell that story. I didn't want to go back there. I was always bothered that sometimes Asian Americans looked at it in a very fossilized way as saying simplistically, “Well, yeah, we have been victimized too.” I don't think that as Asian Americans, we can keep on invoking the killing of Vincent Chin and that injustice unless we stand up and fight against the racial violence perpetrated on black and brown Americans, like in the case of Ahmaud Arbrey. The roots of racism are everybody's problem, including ours, and justice is not just us.

I did not want to just do a capsule version of Who Killed Vincent Chin?, but it's now told by people from new Asian communities like Mee Moua who was growing up in Wisconsin when Vincent Chin was killed and as a Hmong refugee, the target of anti-Asian violence in Appleton, Wisconsin. Her world expanded when she went to college and found out about the Vincent Chin case and realized she was not alone and she became an activist, becoming the first Hmong elected to statewide office in history.

With the Pulitzer Prize-winning author, Viet Thanh Nguyen, a Vietnamese refugee who grew up in San Jose, California, in the wake of the Chin murder. His family also was targeted. His parents had a store; he can remember signs going up, accusing the Vietnamese of pushing out other businesses. For Mee Moua and Nguyen to look at the story of Vincent Chin and interpret its meaning for their own communities is powerful. Today, we have to ask about the relevance of the Vincent Chin story. Asians were being scapegoated for the recession in 1982. Unfortunately, we’re seeing the same kind of scapegoating in 2020.

“Asian Americans” explores these cross-cultural links and exchanges. I’d like to hear you talk about these comparative links across racial groups.

The premise of the whole series is: How did we get where we are today, and where are we going next? The fault lines of race, immigration and xenophobia can be traced back to our first arrivals in the United States. It’s in times of crisis that these fault lines erupt and you have things like the racial profiling that results in incarceration during World War II. In the 1950s, you’ve got the crisis of communism versus democracy. During the early 1980s recession, you have the murder of Vincent Chin. After the 9/11 attacks, you have attacks on South Asians and Muslims. Today, we see public leaders referring to this novel coronavirus as the so-called “Chinese virus” or the “kung flu.” We also wanted to track the inter-ethnic relations with African Americans and Asian Americans throughout the whole series.

Throughout my career, people have asked why I don’t focus on Asian American “success stories.” For me, what Larry Itliong, Philip Vera Cruz, and the Filipino farm workers did, in creating what would become an international grape strike and the formation of the United Farm Workers with Mexican American workers—that’s a success story.

In “Asian Americans,” when historian Erika Lee said [in reference to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882] that Asians were America’s first “undocumented immigrants,” I almost fell to the floor. I don't think we can talk about American history without looking at those connections. I think the people whose stories we tell are inspiring. One of my favorite quotes is from entrepreneur Jerry Yang, who said, “When people's backs are against the wall and there's nowhere else to go, you go forward.” That's what we see throughout Asian American history.