Renovated Museum Wing Delves Into Untold Chapters of American History

“The Nation We Build Together” questions American ideals through exhibits on democracy, religion, diversity and more

:focal(742x414:743x415)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/20/3e203b41-6f02-4202-b9ed-eb695c4b2ea0/gw_landmark_jn2017-00851web.jpg)

A week before the United States’ 241st birthday, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History unveiled a new perspective on how the nation came together—and continues to re-invent itself.

The 30,000-square-foot recently renovated west wing of the museum’s second floor, entitled “The Nation We Build Together,” opened on June 28. It includes four major exhibitions that explore the question “What kind of nation do we want to be?”

The exhibits re-contextualize some of the museum’s core holdings, presenting hundreds of items previously hidden away in storage. “The Nation We Build Together” offers a fresh look at the events that built America through its exploration of “the common values of freedom, liberty and opportunity,” according to museum director John Gray. “These American ideals bind us together as a people, all working together to build on and shape this great nation.”

An effort to share more voices and backgrounds in America’s story is at the heart of the new exhibitions: “American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith” in the Linda and Pete Claussen Hall of Democracy; “Many Voices, One Nation” in the Hall of the American People; “Religion in Early America” in the new Nicholas F. and Eugenia Tubman Gallery; and interactive displays of “American Experiments” in the Wallace H. Coulter Unity Square.

Additionally, “Within These Walls,” a popular installation that traces the history of a single Massachusetts house, has been updated. Much of the new information revolves around a former enslaved man known as Chance.

The museum’s recent renovations began with the re-opening of a first floor “innovation” exhibit space in 2015. The last part of the renovation—an exploration of culture on the museum’s third floor—is set for completion in 2018.

The cost of the full renovation was $58 million in federal funds, plus an additional $100 million in private support. The American History Museum is the third most popular Smithsonian site, with 3.8 million visitors last year and 1.8 million as of May 2017.

Controversy has always been part of the American story. Horatio Greenough’s 12-ton marble statue of George Washington heralds the newly reopened wing; originally commissioned by Congress in 1832 for the centennial of Washington’s birth, it generated criticism soon after its 1841 installation in the Capitol rotunda.

Greenough based his statue on a pose of Zeus, so the president is depicted shirtless. Washington’s nudity disturbed visitors enough to warrant several relocations, so the statue was sent to the East Lawn of the Capitol, the front of the Patent Office, the Smithsonian Castle and finally the American History Museum (then known as the National Museum of History and Technology) when its McKim, Mead and White building opened on the Mall in 1964.

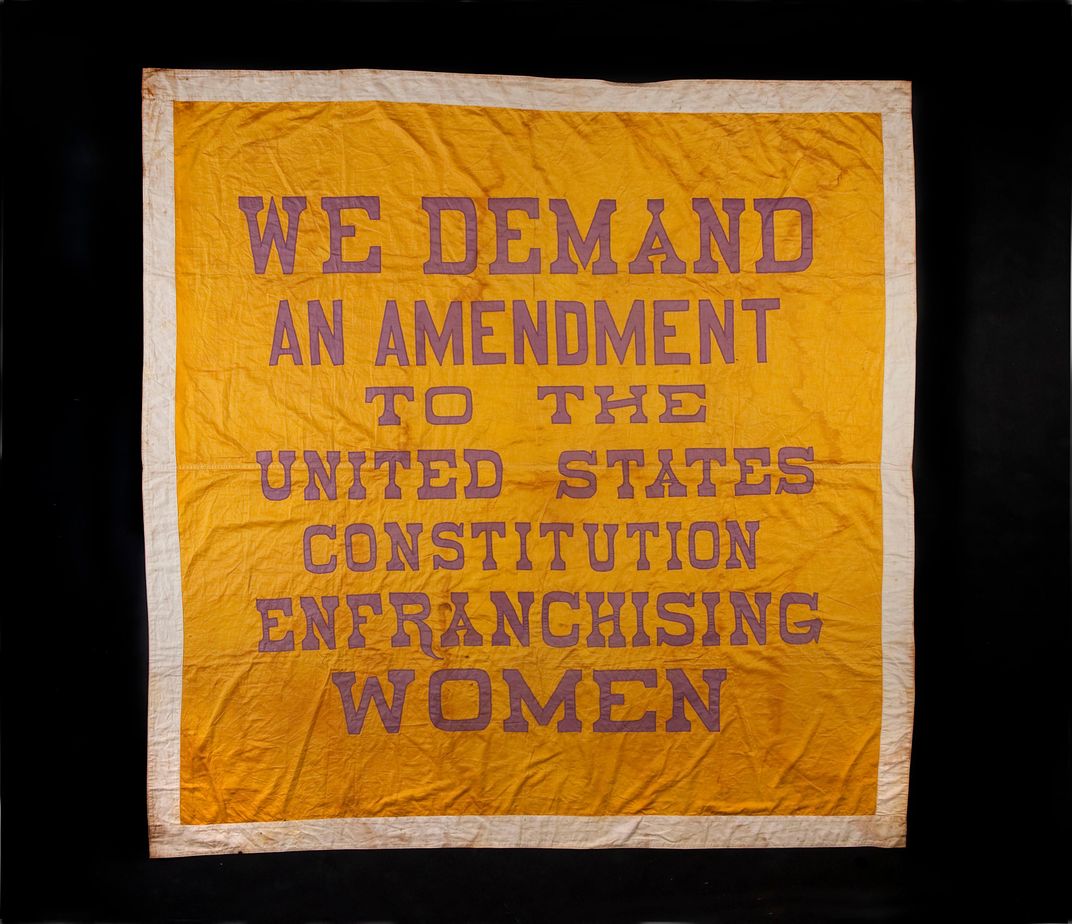

Today, Greenough’s creation points visitors toward the “American Democracy” exhibition, which presents a streamlined look at the rise of the nation through iconic treasures such as the writing box Thomas Jefferson used to draft the Declaration of Independence and the inkstand Abraham Lincoln used to draft the Emancipation Proclamation.

To these have been added the table on which Elizabeth Cady Stanton drafted the Declaration of Sentiments, and a yellow feather pen that Pennsylvania Gov. William Cameron Sproul used to sign his state’s ratification of the 19th amendment giving women the right to vote.

Additional artifacts include the pen Ulysses S. Grant used to sign the proclamation of the 15th Amendment, which enfranchised African American men, and the pen President Lyndon Johnson used to sign the Voting Rights Act 95 years later.

Among the 900 or so objects on display is the large, fanciful 19th-century Great Clock of America. The clock features iconic figures and scenes animated through a series of moving parts.

In another corner, cases of campaign buttons rest below monitors displaying presidential campaign commercials. The screens spill onto the ceiling of the gallery, entertaining visitors with clips ranging in date from 1952 to 2016.

Other familiar items from the 20th century include chairs from the televised 1960 Kennedy-Nixon debate and a magnifying glass used to examine hanging chads during the 2000 Florida presidential recount.

Some items speak to the diversity of America: Manfred Anson escaped Nazi Germany as a teenager. He created his folk art “Liberty Menorah” to mark the 1986 centennial of the Statue of Liberty.

Lady Liberty appears throughout the refurbished museum space: There is a nine-foot-tall replica made entirely of LEGO bricks on the museum’s first floor, an eight-foot-tall wooden sculpture dating to around 1900 and a tomato-carrying papier-mâché version used in a 2000 Florida protest.

The breadth of culture that defines America is showcased in “Many Voices, One Nation.” The exhibit features 200 museum artifacts and 90 lent items, including a painted elk hide found in the Southwest circa 1693, a 19th-century Norwegian bowl brought by immigrants and a trunk carried by a gold miner seeking his fortune in California.

Diverse communities are also represented. There are artifacts from a utopian Icarian group that moved into Nauvoo, Illinois, after the Mormons traveled west, the now-abandoned all-black community of New Philadelphia, Illinois, and the Anishinaabe people of northwestern Michigan.

“Many Voices” includes recent original scholarship as well, says Nancy Davis, curator in the division of home and community life, project director and one of the organizers of the exhibition.

Contemporary history is reflected in a dress from one of the more than 14,000 Cuban children who escaped to the U.S. in the early 1960s, as well as equipment used by a refugee youth soccer team created in an Atlanta suburb just a decade ago.

Davis says the sheer variety in the display shows that history continues to be written.

“The collecting we had been doing for the last eight years is actually broadening our collection, because it had been, as you know, very Eurocentric—and very East Coast-centric,” she explains. “This exhibit is an outgrowth of a new thinking of collecting for our division of home and community life.”

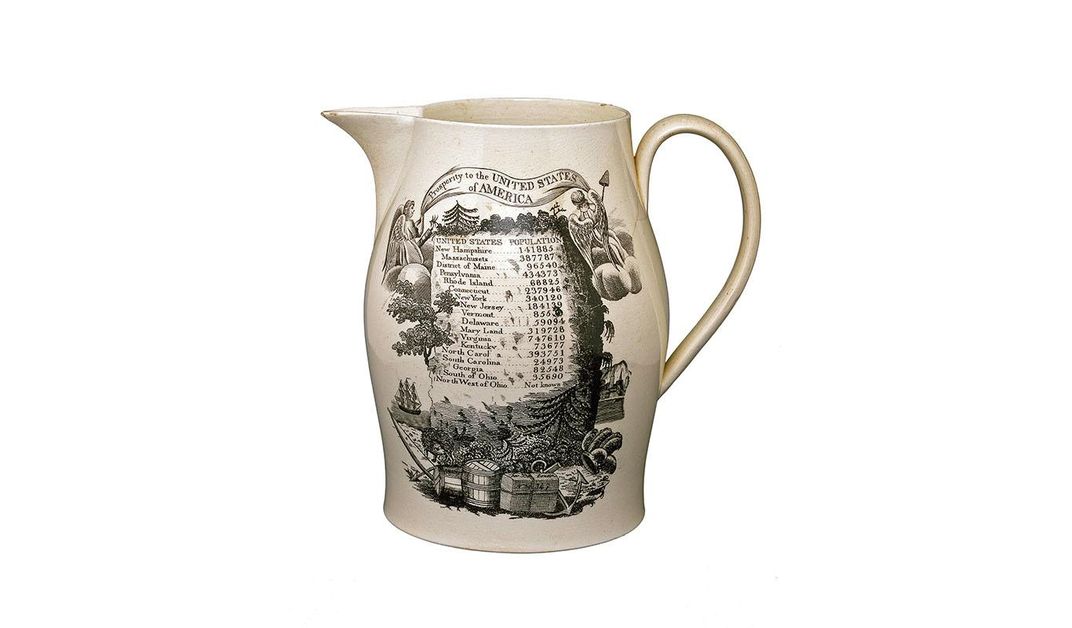

This broadening in scope is also apparent in “Religion in Early America,” a temporary exhibition that focuses on spirituality between the colonial era and the 1840s.

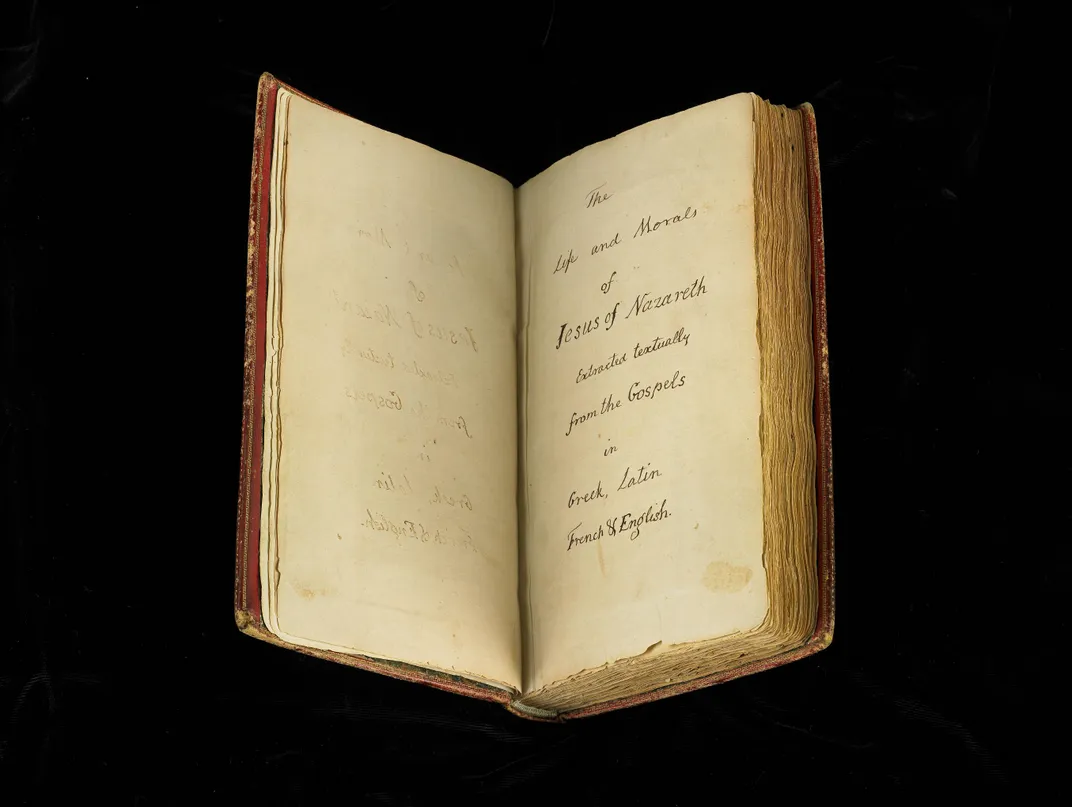

Christianity is represented by George Washington’s christening robe from 1732, the George Mason family baptismal bowl (also used for chilling wine), Thomas Jefferson’s modified personal Bible and the cloak of Quaker minister Lucretia Mott.

Other religions are highlighted as well: The display includes a Torah scroll from New York’s oldest synagogue (partly burned during the Revolutionary War), wampum beads used by Native Americans and a 19th-century Arabic manuscript written by an enslaved Muslim in Georgia.

It’s estimated that 15 to 20 percent of enslaved people were Muslim, says Peter Manseau, the museum’s curator of religion. “Though that tradition was lost through the conversion to Christianity, certain isolated island plantations kept the traditions longer.”

Rare notes from the first Book of Mormon are on display, as is a cross from one of the ships that carried the first English Catholics to Maryland.

“The real power of an exhibit like this is you’ll come looking for your own story, but then you’ll see these other objects and realize it’s all part of the same American story,” Manseau says.

The “Religion in Early America” exhibition will be up for a year; the other exhibitions are “permanent,” meaning they will be up through the country’s 250th birthday.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a9/ad/a9ad8316-1d2c-41fc-be47-04d6b70ec612/declaration_of_sentiments_table_.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d5/54/d5542abf-f816-47fd-acd5-375a524f14f5/uncle_sam_statue_bl_fig_3web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)