The Renwick: Finally The Gem It Was Meant to Be

When the newly renovated museum reopens this month, one of Washington D.C.’s most storied buildings will be elegantly reborn

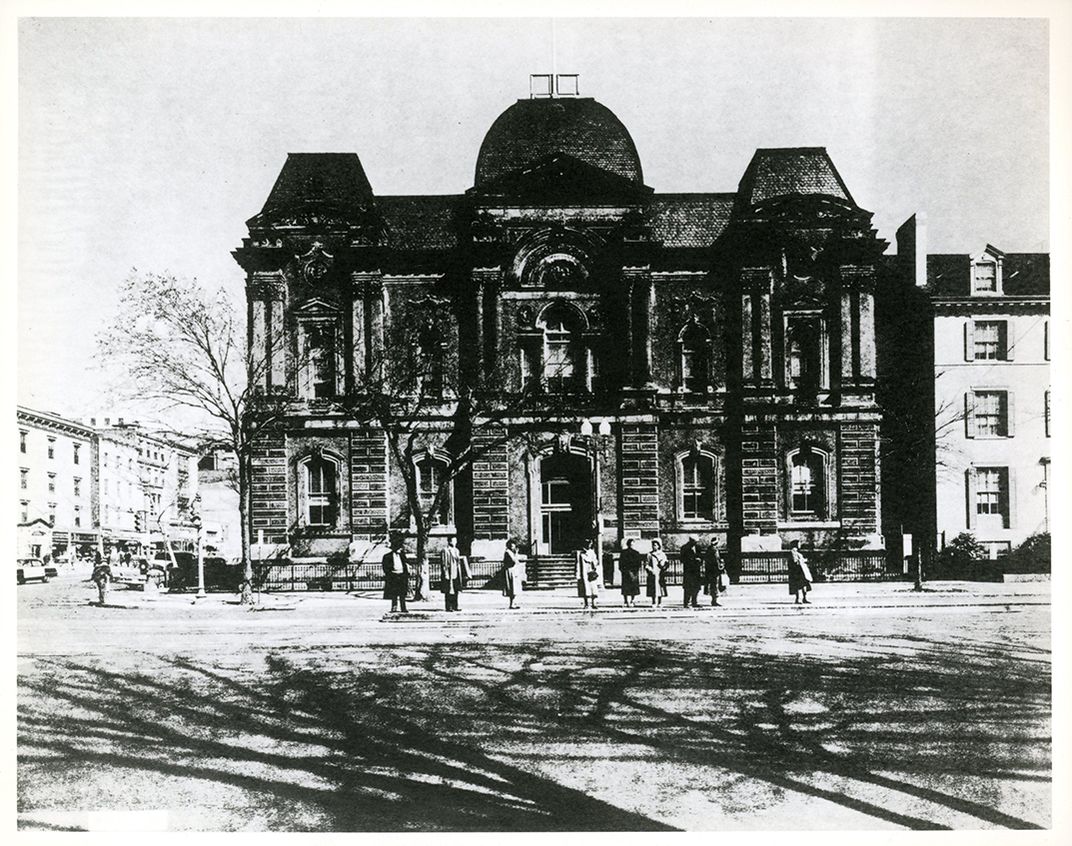

During the Civil War, the ornate building at Pennsylvania Avenue and 17th Street, diagonally across from the White House, was a warehouse stuffed with army blankets and uniforms. This fall, after a century and a half of use, misuse, confusion and narrow escapes from destruction, it is reborn as one of the most elegant public spaces in the capital and the nation.

The Renwick Museum, now reimagined and renovated, is qualified once again to be called the "American Louvre," after the Paris museum that inspired it. It was erected just before the Civil War—the first building in America designed specifically to be an art museum—by one of the country's most distinguished architects, at the bidding of Washington's richest and most generous citizen.

The banker and real estate magnate W. W. Corcoran had grown up in Georgetown and made enough money to repay his good fortune with vast good works. He was a major backer of the long-running Washington Monument project, and supported causes and institutions at home and abroad.

He once traveled all the way to Tunisia to bring back the remains of John Howard Payne, who wrote "Home, Sweet Home," and rebury them beneath a fitting monument in Oak Hill, a cemetery that he deeded to the city.

After touring Europe in 1855, Corcoran decided that Washington needed a proper art museum, and he had just the site for it, around the corner from his imposing mansion on Lafayette Square.

To design it, he brought in New Yorker James Renwick, Jr., an educated and experienced engineer who had taught himself architecture and carried off the career change brilliantly. Renwick had designed the red brick castle of the Smithsonian Institution alongside the National Mall, plus a variety of important churches, mansions and college buildings, and soon would begin his best known project, St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York City.

But before his Corcoran building was finished, war broke out and Corcoran himself, a friend of Robert E. Lee who quietly sympathized with the South, moved to London and Paris for the duration.

Although the words "Dedicated to Art" crowned the gallery's facade, the government requisitioned the building for army use, and made Corcoran's rural estate a military hospital. It wanted to take his Lafayette Square mansion, too, but the French minister moved in first, claiming to have leased it from Corcoran. In short order, the army turned the would-be museum into a storehouse and then headquarters for Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs.

Not until eight years after the war did the grand Empire-style building finally open amid a bright celebration as the Corcoran Museum of Art.

Deeding it to the public, Corcoran stocked it first with works from his own home and many of those rescued from a disastrous 1865 fire at the Smithsonian Institution’s Castle building. He gradually expanded its holdings and supported it through his vigorous old age. (In 1880, the New York Times noted his sartorial splendor—always wearing white gloves and carrying his gold-headed cane, he had "the reputation of being the neatest old man in Washington.") According to his 1888 Times obituary, "his memory will be more deeply cherished in Washington than that of any man who ever lived there."

But in 1897, the still-growing Corcoran museum had to move into new, bigger quarters three blocks south. Then, for more than half a century, the old gallery housed the U.S. Court of Claims, until the court announced in 1956 it wanted to tear it down for more office space.

That is when the snail federal bureaucracy collided with the formidable opposition of the new president's wife, Jacqueline Kennedy.

Mrs. Kennedy made a personal campaign of preserving the White House and its historic neighborhood from deterioration and demolition. She stood up against plans to replace the period houses around Lafayette Square with characterless office buildings like those that were blighting much of downtown Washington in the name of urban renewal.

Passions rose: one outvoted member of the Fine Arts Commission wrote: "I just hope that Jacqueline wakes up to the fact that she lives in the twentieth century."

And when the General Services Administration proposed demolishing the gallery, Mrs. Kennedy wrote eloquently: "It may look like a Victorian horror, but it is really quite a lovely and precious example of the period of architecture which is fast disappearing. . . . we think of saving old buildings like Mount Vernon and tear down everything in the 19th Century—but, in the next hundred years, the 19th Century will be of great interest and there will be none of it. . . ."

Even after the trauma of President Kennedy's death in November 1963, she did not give up her campaign.

The gallery was still standing, but its future was undecided. President Lyndon Johnson suggested making it a conference center to accommodate foreign dignitaries using Blair House next door.

But in 1964, S. Dillon Ripley, the new secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, persuaded Johnson that the gallery could feature unique displays of American folk and decorative art, plus that of foreign nations when their envoys were visiting the capital. The Smithsonian took over the following year, renaming the building for its architect and beginning a much-needed roof-to-basement, inside-and-out overhaul.

When the redone Renwick Gallery opened in 1972, The Washington Post called it "a triumph of American culture over the spiteful neglect with which we treat our cities."

The American Institute of Architects said: "The Renwick Gallery is a masterpiece of creative restoration, a lesson that should be applied in every town and city across the nation. . . ."

Gradually the gallery began to concentrate on post-World War II American arts and crafts, and was busily successful in that role for more than 40 years before the latest, $30 million renovation began in 2013.

Among other changes, outdated systems have been replaced and vaulted ceilings restored in major exhibition halls. Altogether the two-year project has brought out detail and brilliance that Corcoran and Renwick dreamed of back when James Buchanan was in the White House.

Today, Washington may have more institutions that call themselves museums than any other city in the world. Some of them have long and inspiring histories, but none has come through war and weather, neglect and controversy more successfully than the Renwick Gallery that will reopen in mid-November, finally the gem it was meant to be.

The Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum reopens after a two-year, $30 million renovation on November 13, 2015.

American Louvre: A History of the Renwick Gallery Building

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)