This Tilting, Twirling Artwork, Sculpted Entirely of Sticks, Is Having a Shindig

Stick man Patrick Dougherty’s sculptures evoke a playful urge to crawl inside

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/05/26/0526d3f9-a4d4-4359-85be-03ab1095a8a6/doughertyshindiggalleryweb.jpg)

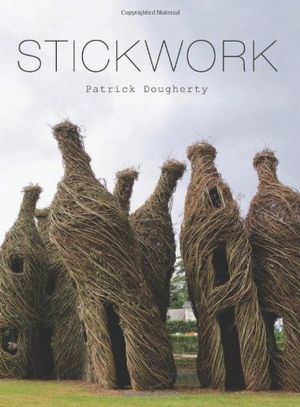

There’s a magical ascendency to Patrick Dougherty’s work. The world-renowned sculptor, who twists switches and saplings into towering whimsical structures, holds a kind of sovereignty over the simple stick.

You wouldn’t immediately recognize his supremacy upon meeting the mild-mannered craftsman from North Carolina, but he has created more than 250 site-specific sculptures on four continents over the past three decades using hundreds of truckloads of sticks.

“A stick is an imaginative object,” says Dougherty, while taking a break recently from the installation of his new work Shindig at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

A parade of playful tent-like structures lean against the gallery walls or appear to be roaming about the 2,400 square-foot room. Soaring 16-and a-half-feet-high, the tips of their switches tease at the ceiling lights of the newly renovated museum. They look, in fact, like individuals possessing a hint of a mischief, as if when the lights go down at night they might take off in a whirl of dance.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/68/4068c81a-79a7-40b9-97e2-8ded6fb77157/doughertybycalicchioweb.jpg)

But by day, they evoke that primordial need for shelter, and visitors will likely want to hide inside of them.

“I think we have a kind of shadow life of our hunting and gathering past, especially in our childhood play. Because a stick—a piece of wood—is an object that has an incredible amount of vibration for us,” says Dougherty. In a child’s hands, a stick becomes a marching baton, a flute, a sword or even just a simple tool to poke at, or flick something away.

“Sticks really give me a lot of energy,” he says. “I’m very keen to the material and I feel like I sense the potential of a sapling.”

Indeed, since his first visit to the Smithsonian Institution in 2000 when he built Whatchamacallit at the National Museum of Natural History, Dougherty has become known as the "Stickman." And like a capstone to a full and engaging career, he returns now to welcome the Renwick Gallery back to life as it reopens on November 13 after a two-year, $30 million renovation, and as one of nine contemporary artists in the museum’s inaugural exhibition entitled “Wonder,” named for the awe and splendor that these works bring to the museum’s galleries.

To Dougherty, the stick is a tapered line of a drawing. He thinks of his works as illustration and the sticks as the lines of his drawing. But the ease with which he does his work is illusory. There's a lot more to it then it seems. Only after years of painstaking craftsmanship, can he build them as if by magic.

First there is the gathering of the material. Volunteers clamor to help. “There are a lot of closet stick gatherers out there, it turns out,” he says with a chuckle.

And then later, the volunteers join him to build the structure. Dougherty starts the process, crafting out the base of the structure, marking it with paint or rope and then weaving it all together stick after stick before finally finishing it, loosening, clipping and correcting, with his only tool—a pair of pruning clippers. Sometimes his volunteers are a little too good at weaving, he says, a little too tight sometimes. "I'll go around and loosen it up and give the surface a sense of the flyaway."

And the weaving is nothing like that of a basket. “Don’t go horizontal or vertical,” he tells his helpers. “It’s not geometric. We want it to be more loose and friendly.”

Dougherty found his artistry only after a first career as a hospital administrator, But in the early 1970s, after leaving his job to care for his two children while his first wife worked, he bought property and built a home by hand, using as guidance the how-to Foxfire books, popular with the back-to-the-land movement of the time.

Finding in that creation his passion, he went back to school and sought training as an artist. His first sculpture—a funerary piece, evocative of a cocoon—he built out of maple saplings at his backyard picnic table.

“One could imagine a kind of personage in there for its final resting place,” he recalls. The work entitled Maple Body Wrap was included in the North Carolina Biennial exhibition. And Dougherty’s career took off from there.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8e/65/8e656e8b-3146-407a-9493-82b674aa6d01/doughertyshindiginstallweb.jpg)

His influence was the artist Robert Smithson, known for his provocative large scale earthworks. “I was kind of bent on making really big things. Smithson’s work freed up my mind. I didn’t have to follow the normal rules. Smithson stepped out of line, but for me that was the beginning,” he laughs.

The busy artist has been traveling the world making one monumental sculpture after another from Scotland to Korea to Australia and across the United States, one every three weeks after which he takes a week off—as many as ten a year. He’s booked solid through 2017. Here in Washington, D.C., the sculpture he’s crafted is one he thinks of as “natural beings, windswept, or energized and activating the space.”

An energy perhaps that is channeled from their creator, who beneath his thoughtful and patient demeanor seems never to rest. (He didn’t own a sofa until his second wife, Linda Johnson Dougherty, the chief curator of contemporary art at the North Carolina Museum of Art, made him buy one—because he never sat down.)

The challenge of his schedule and the constant travel is underscored by the simple way he gathers his materials, patiently teaching, instructing and showing his volunteers as if he is mentoring hundreds of future stick sculptors. He explains the best wood—maple saplings are his preference but sweetgum will do. No, he doesn’t like poplar—cutting and bundling, and then bringing them to the next location.

At the Smithsonian, the sticks had to be custom prepped. Leaves were removed and then the wood was frozen first to kill pests and then treated with a fire retardant.

Each site where he is invited to work is a blank page or canvas, says the artist who rarely comes with a design in mind.

“I don’t do research. I try to remember how I feel about a place and I make word associations with each location so that I can try to get something going,” he says. It might be something someone says. Or the way the trees line up on the horizon or the way a rooftop of a nearby building fits into the landscape. And soon the creative process begins. “I start imagining that I could make something provocative in that space.”

Dougherty, dressed in jeans and greeting a reporter with a solid workman's handshake, explains his art in a refreshingly uncomplicated manner.

How long do they last? "One year and one pretty good year." Why do they lean? "For fun." Why are they so inviting? “Everyone, even adults, responds to the idea of simple shelter. There’s a call to just go in there and sit.”

And why call this work Shindig? “They are having a hell of a good time.”

Patrick Dougherty is one of nine contemporary artists featured in the exhibition “Wonder,” on view November 13, 2015 through July 10, 2016, at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

Wonder

Stickwork

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)