Renaissance Europe Was Horrified by Reports of a Sea Monster That Looked Like a Monk Wearing Fish Scales

Something fishy this way comes

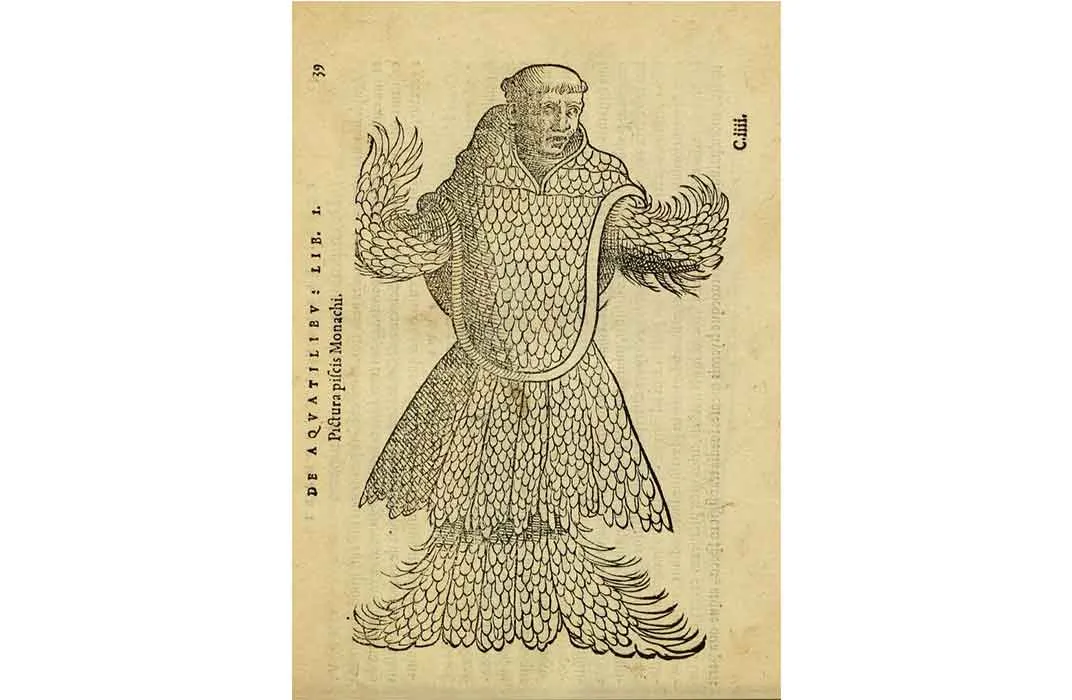

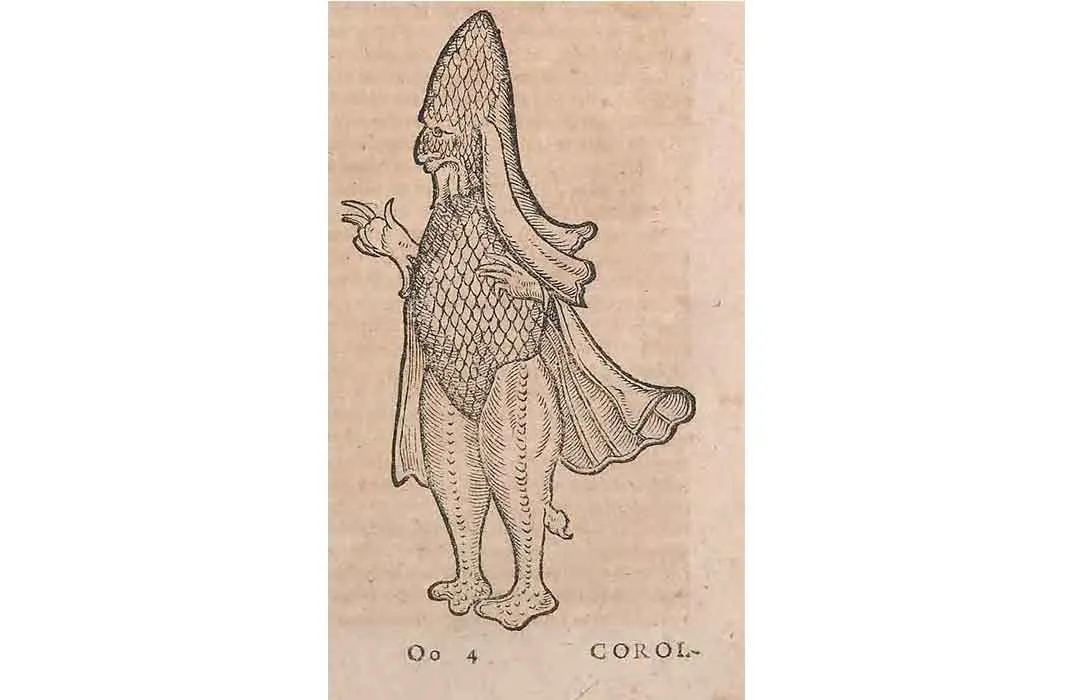

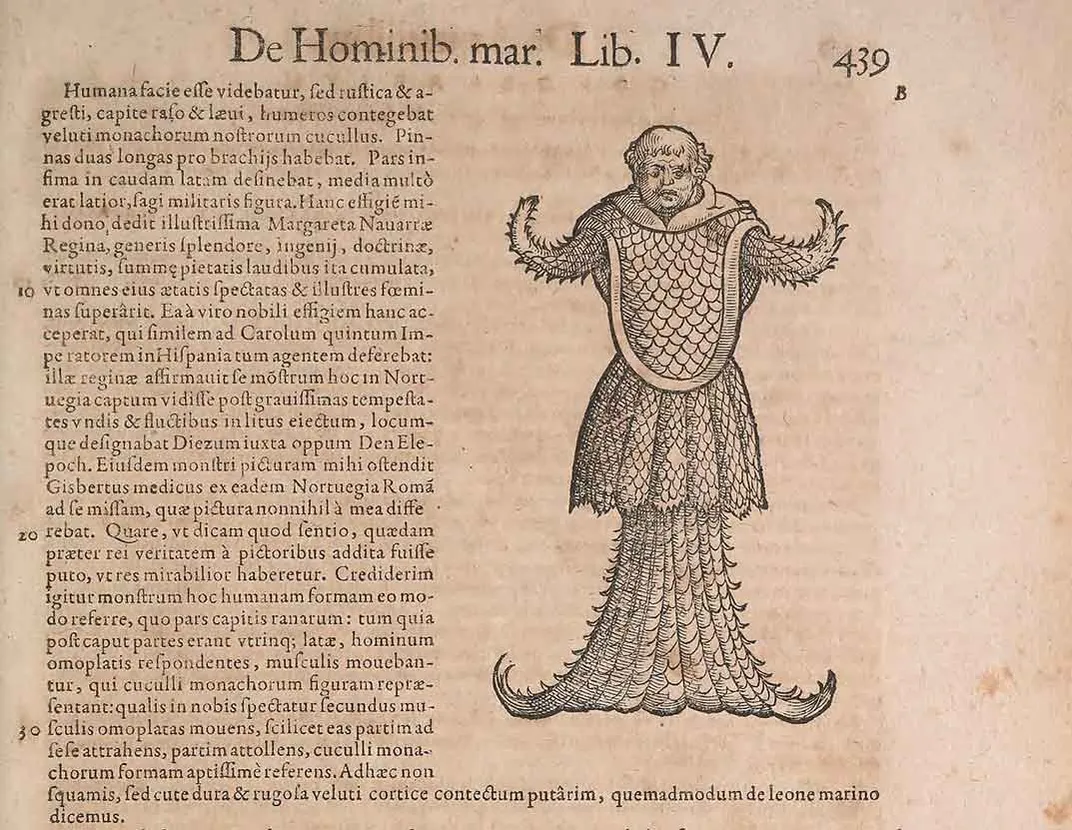

In the 16th century, the so-called “sea monk” became the talk of Europe. Drawings of the half-man, half-fish “monster” appeared in naturalists’ tomes and were circulated among naturalists and members of royal courts across the continent. It was the end of the Renaissance, when Europeans were enamoured with art, science, philosophy and exploring the natural world.

But over the centuries, the creature, and talk of it, faded into obscurity. Whatever it was, it was never definitively identified. The lack of an answer has given scientists and folklore-loving researchers something to chew on over the years.

The sea monk was first described by a French naturalist and ichythyologist, Pierre Belon, in 1553, and again by a French colleague, Guillaume Rondelet, in 1554. The creature was also included in a 1558 volume of the widely-read and respected Renaissance natural history encyclopedia, Historiae Animalium, which was compiled by Conrad Gesner, a Swiss physician and professor. These rare books are all held in the collections of the Smithsonian Libraries and have been digitized for public viewing.

The sea monk is just one of a host of creepy monsters and ghoulish visuals culled from rare and antique books and curated this month on the website PageFrights by the Smithsonian Libraries and other archives, museums and cultural institutions around the world to share for Halloween.

Sometime between 1545 and 1550, the peculiar sea monk washed up on a beach near, or was caught in the Oresund, the strait between modern-day Denmark and Sweden. The actual circumstances of its discovery have never been well-documented. None of the naturalists of the day who drew or discussed the animal had ever actually laid eyes on the sea monk specimen. It was described as almost eight-feet-long, having mid-body fins, a tail fin, a black head, and a mouth on its ventral side.

A published account in the 1770s—which drew upon the Renaissance scholars’ work—described it as an animal with “a human head and face, resembling in appearance the men with shorn heads, whom we call monks because of their solitary life; but the appearance of its lower parts, bearing a coating of scales, barely indicated the torn and severed limbs and joints of the human body.”

That description was unearthed by Charles G.M. Paxton, who, along with a colleague, published in 2005 a full accounting of their research into the sea monk’s origins. They also offered their own take on its true identity. Paxton, a statistical ecologist and marine biologist at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, says the sea monk is just one of his many forays into monster mysteries.

“For the past 20-odd years or so, I’ve had a strange hobby, which is exploring the hard science behind the accounts of sea monsters,” says Paxton.

The sea monk intrigued him because it seemed to him that maybe, in the attempts to classify the creature, something obvious had been overlooked. For instance, “monkfish” is a common name in Britain for a fish found in the North Atlantic.

Paxton was not the first in modern times to try to determine the sea monk’s identity. Japetus Steenstrup, an influential Danish marine biologist, delivered a lecture in 1855, in which he postulated that the sea monk was a giant squid, Archeteuthis dux. It wasn’t too surprising, given that Steenstrup was an authority on cephalopods, and one of the first zoologists to properly document the existence of the giant squid, says Paxton.

Steenstrup gave the sea monk the name Architeuthis monachus (Latin for monk). He noted that the sea monk’s body was similar to a squid; it also had a black head and red and black spots, just like a squid. He believed that some of the early descriptions mistakenly said the sea monk had scales, noting that Rondelet claimed it was scaleless—as would be true of a squid.

Paxton, however, isn’t buying it. He says in his paper that while Steenstrup’s giant squid was a good explanation for the many sea monsters described in the 16th and 17th centuries, “he may have been a little overenthusiastic in implicating Architeuthis as the prime suspect for the sea monk.”

Others have suggested that the sea monk was an anglerfish (Lophius), a seal, or a walrus. Another candidate is a “Jenny Haniver.” That’s what you call a tricked-out specimen that is fashioned into a devil or dragon-like creature by modifying a dried carcass of a shark, a skate or a ray.

No one knows where the term Jenny Haniver (sometimes Jenny Hanver or Havier) came from, but the trinkets were in existence in the 1500s, says Paxton. Even so, if the sea monk was found alive when discovered—as the accounts have suggested, it could not have been a Jenny Haniver, says Paxton. Also, the dried sharks are smaller than the sea monk.

Paxton says the most likely explanation is that the sea monk was a species of shark, known as the angel shark (Squatina), given its known habitat and range, coloration, length, subtle scales, and pelvic and pectoral girdles that might appear to be a monk’s habit.

“If you put a gun to my head and force me to say what the answer is, I’d say Squatina,” says Paxton. But, he says, “we can’t go back in time, so we can’t say for sure what the answer is.”

Paxton is continuing his investigation into the sea monk, and a similar creature from that period, known as the sea bishop.

Both of those animals caught the attention of Louisa Mackenzie, associate professor of French and Italian studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. The sea creatures serve as a window into Renaissance scholarship and the history of scientific inquiry, along with an animals’ place in the Anthropocene world, says Mackenzie.

The fervent interest in the sea monk and other creatures in the 16th century indicates that scientific inquiry was a serious business. “We might look at these images today and find them quaint, amusing, superstitious, or fantastical—proof of how ‘unscientific’ Renaissance science was,” says Mackenzie.

But, she argues in a recent chapter about the sea monk and sea bishop in the book Animals and Early Modern Identity, that those inquiries deserve more respect. “What I was trying to do with this chapter was to ‘call out’ our own tendency to not take these creatures seriously as sites of investigation,” Mackenzie says.

So, did 16th century scholars and royals truly believe the sea monk was a fantastical half-man, half-fish?

Paxton says it’s hard to know what they actually believed, but that some may have embraced the idea of a chimera. The naturalists most likely saw a resemblance, and then decided it was expedient to describe the sea monk in terms that would be familiar. “My gut feeling is that they weren’t suggesting there was a whole society of merpeople under the sea,” Paxton says.

But Mackenzie says “it’s very possible that naturalists believed it to be a true hybrid, and that, possibly, it was to be feared,” especially, since “theology was baked into natural history at the time.”

Paxton found a report that upon hearing of its discovery, the King of Denmark ordered that the sea monk be immediately buried in the ground, so it would not, according to the account, “provide a fertile subject for offensive talk.”

What kind of talk? Paxton theorizes that perhaps the sea monk could have represented some sort of primacy of Catholicism, with lots of monks swimming under the sea—given that monks were traditionally Catholic, not Protestant.

Remember, he says, that this discovery came during the time of the Protestant Reformation, when Europe was fulminating with religious sectional discord.

Paxton is moving on to his next mystery—a decidedly more ominous creature: a man-eating sea monk discovered during the medieval period.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/dc/dedc97a8-34be-4640-8a07-ad43971eb326/rondeletseamonkweb.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)