The Return of Dorothy’s Iconic Ruby Slippers, Now Newly Preserved for the Ages

The unprecedented conservation of the Wizard of Oz shoes involved more than 200 hours, and a call from the FBI

The Smithsonian conservators were nearing the end of approximately two years of work on one of the most beloved artifacts from movie history, the Ruby Slippers worn in The Wizard of Oz, when they received a call from the FBI. Another pair of the shoes had turned up, the bureau said. Would they take a look at them?

The Smithsonian’s Ruby Slippers that the National Museum of American History’s Preservation Services department had been examining go back on view in the museum October 19 following what is believed to be their most extensive conservation since Judy Garland wore them in the 1939 film.

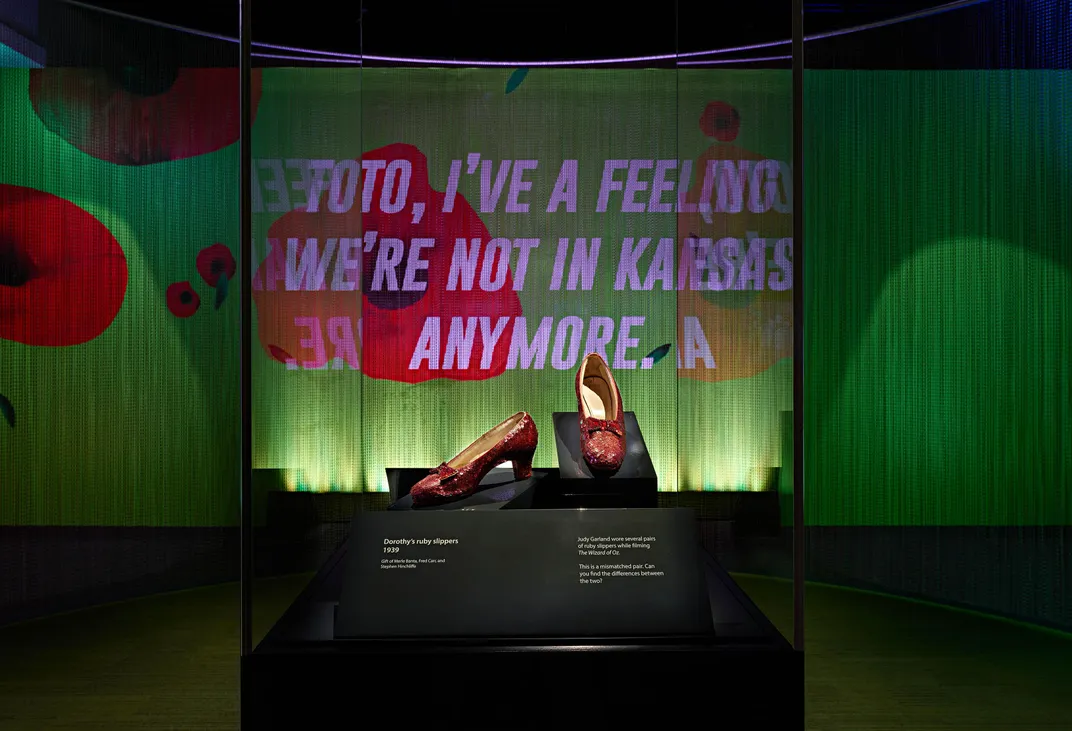

The slippers have a new home in a large gallery meant to evoke Emerald City. Quotes and stills from The Wizard of Oz and a mural featuring bright red poppies created by the Washington, D.C. art and design firm No Kings Collective covers the walls. Additional artifacts from the film are on display—the Scarecrow’s hat, which actor Ray Bolger’s wife donated to the Smithsonian in 1987, and a wand used by Billie Burke, who played Glinda the Good Witch of the North, in promotional materials for the film. “We’ve connected with people who care about the film, who have some of the other props from the film,” says Ryan Lintelman, curator of entertainment at the museum. “That whole community of Oz fans, we really want to keep them engaged here and be this pilgrimage place for them.”

The museum’s pair of Ruby Slippers is one of four from the film’s production known to have survived. Another one of those pairs disappeared from the Judy Garland Museum in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, in 2005. Those were the shoes the FBI recently called about.

An estimated tens of millions of people have viewed the Ruby Slippers at the American History Museum since an undisclosed donor gave them to the institution in 1979, according to Lintelman. Prior to their recent conservation, the shoes had been away from the public for only short periods. “Any time that we take the Ruby Slippers off display we immediately hear about it from guests,” he says. “When people see them in person they’re so surprised to see that they’re small, but it brings home the fact that Judy Garland was 16 years old when making the film. . . . It’s a very recognizable and understandable object.”

Rhys Thomas, author of the comprehensive 1989 book The Ruby Slippers of Oz, recalls visiting the shoes at the Smithsonian decades ago and seeing a young girl approach the display case, put her hands on it, and say, “Magic.” “The Ruby Slippers are an enduring symbol of the power of belief,” he says. “The Wizard of Oz is America’s only true original fairy tale. . . . Then you combine it with star power, Judy Garland. . . and you get an iconic piece of cultural heritage. People just won’t let go of it.”

Hollywood memorabilia did not always get the attention or fetch the prices it does today. Few artifacts from cinema history are as revered now as Dorothy Gale’s Ruby Slippers. After filming, at least three of the pairs went into storage at MGM. A costumer named Kent Warner found them in 1970. He kept one pair for himself, sold one pair to collector Michael Shaw for $2,000 (along with other costume items), and gave a pair to MGM to auction. He found a fourth pair, which looks different and was used only in screen tests, and sold it to the late actress Debbie Reynolds, reportedly for $300. As far as the public knew, the auction pair was the only one in existence. Those shoes sold for $15,000.

As Thomas wrote in his book, an updated version of which is in the works, as news broke about the auctioned pair, a woman in Tennessee came forward with yet another pair, saying she had won them in a contest soon after the film’s release. That made four sets of Ruby Slippers, plus the screen-test shoes.

Since then, no new pairs have surfaced. The person who bought the shoes at the MGM auction donated them to the Smithsonian several years later. The remaining pairs changed hands and climbed in value over the years. A group of collectors and investors purchased one of the pairs in 2000 for $666,000. (The group listed them for sale this past spring for $6 million.) Reynolds sold her screen-test pair in 2011 to an anonymous buyer for $627,300.

In 2012, a group purchased a pair for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences museum, set to open in 2019, for $2 million, the most ever paid for the pumps.

The remaining pair—Shaw’s pair—disappeared. In 2005, he loaned the shoes to the Judy Garland Museum, where they were stolen. The thief of thieves left behind a single ruby sequin. Accusations swirled about who was to blame, and Shaw received an insurance payout of $800,000. A decade after the disappearance, an anonymous benefactor offered $1 million for the shoes’ return. But they didn’t turn up. Shaw said at the time, “I have no desire to have them again. After years of bringing joy and happiness to so many thousands and thousands of people by being able to see them, now to me they’re a nightmare.”

With two on-screen pairs away from view and one pair missing, only the Smithsonian’s was available for the public to see. In 2016, the institution launched a Kickstarter campaign to raise money for their conservation. The slippers hadn’t undergone a major conservation since entering the Smithsonian collections, and it’s unlikely they did between filming and their discovery in storage. Nearly 6,500 people pledged almost $350,000 to the campaign, exceeding the initial goal.

“There’s obvious wear of age and in natural deterioration in fading,” says Dawn Wallace, a Smithsonian objects conservator, about their condition before the conservation, but structurally the shoes were stable.

The Smithsonian’s Preservation Services team began by researching and learning as much as they could about the shoes. This included visiting the Academy pair and consulting with scientists at the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute, and experts at the Freer and Sackler galleries, the Library of Congress and the National Archives.

“I knew we had the work cut out for us,” says Richard Barden, the Preservation Services manager. “When you really start looking at the slippers, you see how many different materials they are. And with each material you have to consider its condition, its physical state, what the materials are made of, how they deteriorate, what environmental factors affect them.” A single sequin contains multiple components that the conservators had to consider: a gelatin core, silver lining, cellulose nitrate coating and dye in the coating.

After the research, the conservators spent more than 200 hours treating the shoes. This meant removing surface dirt and stabilizing loose threads. They did this sequin by sequin, under a microscope. For the sequins, they used a small paintbrush and a pipette attached to a hose and vacuum. For the glass beads on the bow, they used small cotton swabs and water. “We had to be careful,” Wallace says. “What we could do with one material, we couldn’t do with one right next to it.” They also stabilized broken or fraying threads with adhesive and silk thread. Over time, some of the more than 2,400 sequins per shoe had rotated or flipped, and they realigned them all.

“This is much more in depth and larger than what we usually do,” Barden says.

As their work was winding down, the conservators unexpectedly came face to face with another pair of Ruby Slippers. During the summer, the FBI emailed them and asked about their conservation work, without saying much else. Then the bureau called and said it had a pair of slippers and asked if the conservators could say if the recovered pair was consistent in construction and material with the Smithsonian pair.

The Smithsonian team knew about the stolen pair from its research. “It was always one of those things, ‘Oh, wouldn’t it be neat if they found the other pair of Ruby Slippers?’ And then when you find out that they did, and you actually get to participate in the recovery and the whole process of returning these iconic items,” says Wallace, the conservator, “was almost like an Indiana Jones moment.”

The team studied the FBI pair for a day and a half. The similarities were obvious. “I would say it was after a little over an hour, we were just looking and we see all the consistencies,” Wallace says. “Everything started to line up.” That included clear glass beads painted red on both shoes, a detail she believed was not widely known.

Soon after, in early September, the FBI announced the case to the public. In summer 2017, a man had gone to the insurance company for the stolen shoes claiming to have information about them, in an attempt to extort the company, the bureau said. Investigators recovered the shoes in Minneapolis in an undercover sting operation about a year later.

The Ruby Slippers have always been “pretty much the holy grail of all Hollywood memorabilia,” says Thomas, the author. But now, according to Thomas, they are entering “a forensic era,” in which people are examining them more closely than ever before, including the Smithsonian conservators and the FBI. “The Smithsonian has now had the opportunity to look at two pairs side by side,” Thomas says. “That’s the first time any two pairs of the shoes have been together in the same room since Kent Warner brought them home from the MGM lot in 1970.”

It turned out that the stolen pair is the mismatched twin of the Smithsonian pair. But given inconsistencies between the two pairs, Thomas believes the mix-up happened at the time they were made, not after filming, as others have speculated.

The Ruby Slippers return to the American History Museum also marks the opening of a newly renovated wing called the Ray Dolby Gateway to American Culture. Other artifacts there include a 1923 ticket booth from the original Yankee Stadium, a costume from the television show The Handmaid’s Tale and DJ equipment from Steve Aoki.

The Ruby Slippers will also have a new specialized display case that can filter pollutants and control humidity and temperature. And it will have an alarm.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)