Revisit the Brutal Fight When Jack Dempsey Hammered the Super-Sized Champ to Claim Title

The crowded scene on a sweltering July day in Toledo is the subject of the Portrait Gallery’s latest podcast episode

:focal(784x243:785x244)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/c4/cfc4b64e-7a76-4d0a-801a-e407c11b9014/npg74detail.jpg)

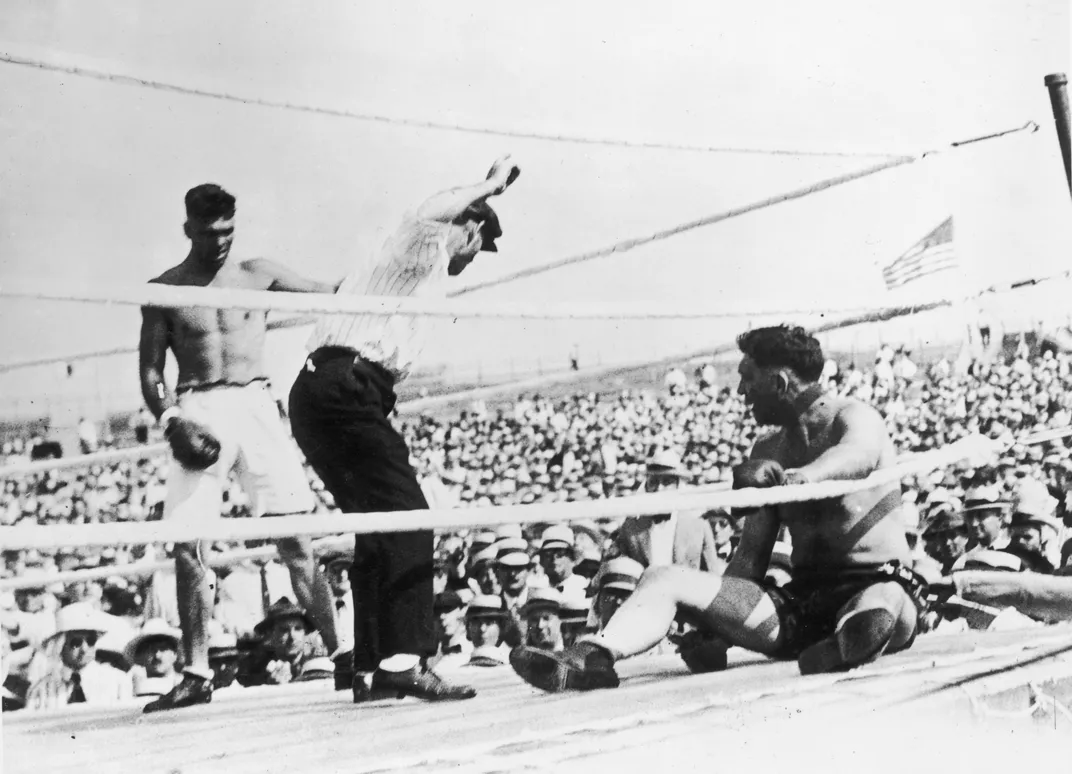

When boxer Jack Dempsey entered the championship match on the Fourth of July 1919, he faced a 6-foot 7-inch, 240-pound incredible hulk with a reach of almost seven feet. In an outdoor ring under a blazing sun that raised the temperature to a torrid 110 degrees, Dempsey crouched as he faced champion Jess Willard, who was almost half a foot taller and 58 pounds heavier than he was. Fueled by ferocity, the 24-year-old challenger toppled Willard seven times in the first round and went on to capture the world title.

Journalist Jimmy Breslin argued that the Roaring Twenties began on that day in Toledo, when celebrities gathered and a sweat-soaked crowd of thousands enjoyed illegal whiskey as they sat beneath a relentlessly glaring sun. Dempsey biographer Roger Kahn reports that promoter George Lewis “Tex” Rickard’s efforts to avoid leaving fans thirsty “was almost certainly the first major bootlegging operation within dry America.”

Listen to the National Portrait Gallery's podcast "Portraits"

Experience the heat, the crowd, and the surprising outcome of the 1919 World Heavyweight Championship.

Boxing fans not only wanted to see the fight: They were curious to see whether Dempsey would reach the contest’s end without suffering a fatal injury. In August 1913, Willard’s right upper-cut drove his opponent’s jaw into his brain, killing him. Before the Dempsey fight, Willard, 37, asked for “legal immunity” in case the challenger landed in the morgue. On fight day, as the bronzed Dempsey looked up at Willard, who was the largest heavyweight champion since the Marquess de Queensbury rules were adopted in 1838, “I was afraid he was going to kill me,” he later said. “I wasn’t just fighting for the championship. I was fighting for my life.”

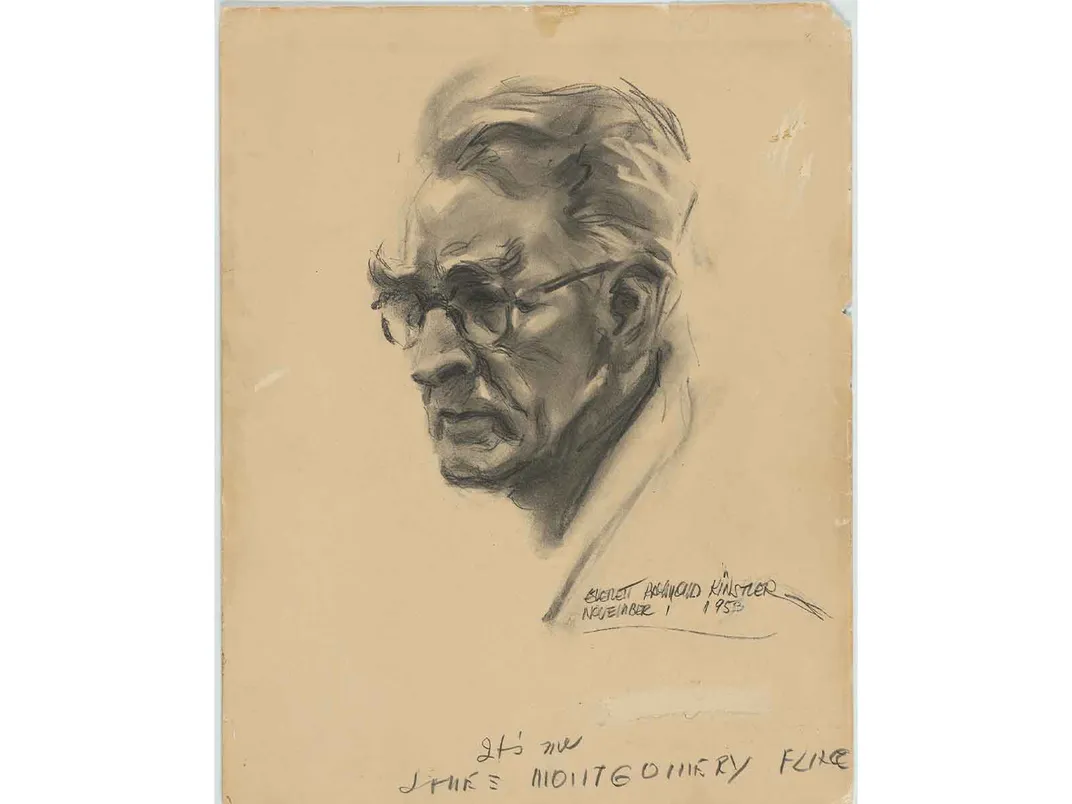

A huge portrait of that fight is highlighted in an episode of the National Portrait Gallery’s podcast series “Portraits.” Throughout the series, curators and educators offer listeners a chance to virtually visit works of art in the museum. A recent episode, “At Home in the Gallery—The Dempsey-Willard Fight,” casts new light on how visitors—whether virtual or in-person—can appreciate the painting that captures a moment in that day. The work by James Montgomery Flagg is a prime choice for education exercises among the gallery’s staff.

Sheltering at home during the Covid-19 crisis, Briana Zavadil White, the gallery’s head of education, explains that the painting is “a wonderful teaching tool.” She describes the work: “The setting is outside. You can see a bright blue sky with white, puffy cumulus clouds. And as my eye wanders backward to the far edges of the portrait, I see a sea of people, so many people. The portrait is infused with red, white and blue—everything from the clothing of the spectators, to the sashes worn by the boxers, to the three American flags” is awash in patriotic colors.

White’s goal is to elicit the skill of “close looking,” which enables viewers of the painting to see details they might otherwise have overlooked. In an interview with National Portrait Gallery director Kim Sajet, White describes how the “jump-in strategy” expands understanding and appreciation of the artwork: “Imagine what it would be like to step inside of this painting” wherever you like. “Once you’re there, I want you to think about your five senses—see, hear, taste, touch, and feel” to sharpen perceptions of the work, which is almost 6 feet in height and more than 19 feet wide. The final step in the process is to ask visitors to sum up their reactions to the painting in six words.

“During a museum visit, Portrait Gallery educators facilitate a ‘Learning to Look’ strategy as a way to begin ‘reading’ the portrait,” White wrote in a 2015 article. “Using inquiry, this technique hooks the participants, and soon a conversation between participants and educators is in full swing.”

The former champ, who lost the title to Gene Tunney in 1926, opened a Manhattan restaurant, which bore his name, and commissioned this portrait, which graced the walls of the restaurant for three decades. When the painting was unveiled, Dempsey’s battered opponent, Willard, declined an invitation to the celebrity-packed event, saying, “Sorry I can’t be there, but I saw enough of you 25 years ago to last me a lifetime.” Dempsey’s restaurant closed in 1974 when he faced a large rent increase. He sadly decided to close its doors and sent the portrait to a new home at the Smithsonian.

To create the artwork, Flagg used photographs taken during the match. He attempted to capture the sense of the smaller, tightly coiled Dempsey challenging his large, looming opponent. Flagg is best known for his World War I Uncle Sam poster, “I Want You.”

When the fight occurred in 1919, it was an extraordinary event—a world championship competition located in a place many might have classified as an American backwater, a small city far from the nation’s largest population centers. Rickard put together this event in Toledo because more than ten railroad lines served the somewhat out-of-the-way venue. For the July Fourth event, he created an octagonal outdoor arena made from Michigan white pine. The best seats sold for $60 apiece. He paid Willard $100,000, while Dempsey received $19,000.

Rickard’s plan was not perfect. The seats oozed sap under the hot July sun, forcing fans to sit on newspapers or cushions. Rickard had insisted that the stands, which were 600 feet across, have only one point of entry or exit. Consequently, the structure was a clear fire hazard, and no smoking was allowed during the fight.

Both fighters went to Toledo before the fight and set up training camps. One day, Dempsey’s father rode over to watch Willard practicing in the ring. When he returned, Dempsey recalled later, “My own father picked the other fighter” to win. Evaluating the competitors, a fight announcer described Willard as having “the muscles of a wrestler and the sheer power of a raging bull when his temper is aroused.” He called Dempsey a young tiger with “two murderous hands.”

When fight day arrived, analysis of the competitors gave way to stunned reactions. After Dempsey first knocked Willard to the mat, “the crowd went stark mad,” reported Damon Runyon, who later contributed to the creation Guys and Dolls. “Hats flew into the air and the pine crater on the banks of the Maumee Bay where the men were fighting erupted with a terrific volume of human voices.” It was a day to remember.

Dempsey’s victory was not without flaws. Assuming that he was victorious as Willard lay sprawled at his feet, Dempsey left the ring during the first round before the referee had counted to ten. The bell ended the round seconds later while the count was still under way. That provided a reprieve for Willard and forced Dempsey to return for Round 2.

Bloodied and battered with fractures in his cheekbone, nose and ribs, plus several teeth knocked out, Willard persevered through the third round, but he and his team literally threw in the towel when the dazed champ was called to his feet for the fourth round. “He was big and good-looking and smiling when he came into the ring. Now, he’s a lurching, tottering wreck of a man,” said an announcer. The fight was called “one of the most savage confrontations since boxers began to wear gloves.”

Though every seat in the 80,000-seat arena was not filled, thousands were. The crowd of white men wearing mostly white shirts and straw boater hats roared throughout the confrontation. Many attendees were journalists. Among them was former western gunfighter, Bat Masterson, reporting for the New York Morning Telegraph, and The New York World sent six writers, led by novelist Ring Lardner.

In 1964, Dempsey’s ex-manager—John Leo McKernan, popularly known as Doc Kearns—told Sports Illustrated that without Dempsey’s knowledge, he had filled the fighter’s gloves with plaster of Paris for the 1919 fight. This, he contended, was the reason for Dempsey’s powerful performance against Willard. However, this allegation has been debunked over the years for several reasons: If Dempsey’s gloves had been filled with plaster of Paris, they would have been noticeably heavy and difficult to raise; the crushing power of plaster of Paris on Dempsey’s opponent would have been equally harmful to his own hands; and while Kearns claimed to have untaped and removed Dempsey’s gloves after the match, someone else actually played that role and noticed nothing suspicious.

The legendary fight still lives in the image created by Flagg. It captures the sense of a mass of humanity watching a hard-fought contest colored by the U.S. patriotism of the World War II years, when Flagg painted it. The National Portrait Gallery’s education programs bring viewers into the details of the image so that they can imagine the heat, smell the sweat, and feel the excitement of an event more than a century in our past.

James Montgomery Flagg gave himself a cameo appearance in the Dempsey/Willard Fight image. Can you find him?

"Portraits," now in season 2, offers a series of virtual visits to the National Portrait Gallery. Join the museum's director Kim Sajet as she chats with curators, historians and others about their favorite portraits. New episodes drop bi-weekly, on Tuesdays, through June.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)