Richard Estes’ Incredibly Realistic Paintings Require a Double Take

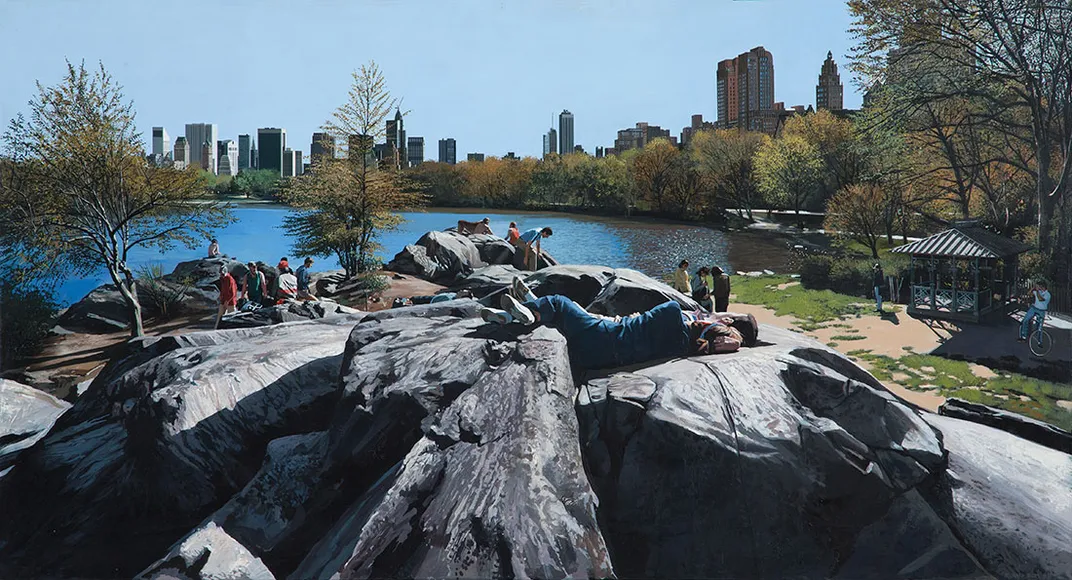

Like stage sets, there seem to be a million stories embedded in the works of Richard Estes, icon of photorealism

Times Square is a good place to go unnoticed. A decade ago, Richard Estes stood there, surrounded by the hustle and bustle of Sesame Street characters and tour bus promoters, and snapped a series of photos. With so many people doing the same thing, it’s unlikely anyone gave much thought to the septuagenarian shutterbug. But for half a century, the art world has lauded Estes for his photorealist paintings, which he creates from photographs. The work that resulted from his Times Square pictures that day and 45 other paintings are now on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The exhibition, “Richard Estes’ Realism,” debuted last week and is open through February 2015. Curators say it’s the world’s most comprehensive Estes exhibition ever, and his largest American showcase in nearly four decades. The show was previously at the Portland Museum of Art in Maine, where Patterson Sims, an independent curator and a friend of Estes, suggested they do a retrospective. “He’s just really interested in painting, and just finding extremely complex and interestingly challenging images to paint,” Sims says.

Estes, now 82, lives and works primarily in New York City and has been spending time in coastal Maine since the 1960s. It’s there that he produces nature paintings, which tend to receive less attention than his iconic New York City works. Both of those locales—street and stream—are in the exhibition, as well as scenes from Paris, London, Venice and elsewhere.

Estes is reticent about the underlying symbolism in his work. “You’re never going to get Richard to admit layers of meaning,” Sims says. “It just isn’t the way he’s built. However, he is a very sophisticated person, so all of those issues come into play.” For example, an Estes trademark is visually bisecting his compositions—a bridge on one side and a river on the other, for example. Sims says that technique presents a “duality” that could stem from the artist’s experience as a gay man. “Interior-exterior is an important thing for him, because I think his interior is quite different from his exterior,” Sims says.

As it has been for artists of so many generations, New York City is Estes’ muse. While he depicts its icons, like the Brooklyn Bridge, he also captures the city as only a New Yorker could, giving life to the city’s anonymous inhabitants—the drug store cashiers working around Valentine’s Day, a young man on a bus near the famous Flatiron Building, which is only subtly reflected in a passing car. “Part of the power of these pictures is that there’s kind of like a million stories embedded in them,” Sims says. “If you go to any of these locales, these are the stage sets on which our lives have been led.”

“It’s such a mess,” Estes says of his city, spoken like a true local. “Everything is chaos.”

His paintings take on new significance as the city changes. “They are totally historical documents,” Mark Bessire, director of the Portland Museum, says about the works. Paintings in the exhibition show Paul’s Bridal Accessories on West 38th Street (since demolished) and telephone booths with rotary phones. Even scenes from a decade ago contain remnants of the past, such as the Fleet Bank and Virgin Megastore in Times Square, which have both since closed. An enormous painting of the Brooklyn Bridge, from 1991, takes on a different tone when viewers spot the World Trade Center in the distance, ethereal, like the memory it has become.

As the city changes, so do photographic techniques, and Estes has adapted. He says that he doesn’t like taking pictures with his cell phone (“I’ve tried it and they’re not really good enough”), but he does use digital film ("Everybody does. You can't even get the other stuff."). He uses iPhoto and Photoshop to prepare photos before recreating them in paint. His paintings aren't always entirely true to life; some contain elements from several different photos. For View from Hiroshima (1990), he didn’t like the landscape as it existed, so he moved some mountains into view.

Photorealism became popular in the 1960s. “He was the hot ticket,” Bessire says about Estes at the time. Then, Bessire says, “the art world kind of turned their back.” But that didn’t stop Estes. “He kept at it, and now,” Bessire says, “they’re coming back to him.”

“Richard Estes’ Realism” is on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through February 8, 2015.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/5e/f55e0dbb-582a-4380-81a7-4da1dc03e929/estes_doubleselfportrait.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/09/c5/09c546a8-dec0-4ebd-812d-0d36644103fb/estes_escalator.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/96/cb/96cb0f4d-0405-4737-ba9d-c4005f166523/estes_columbuscirclenight.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ac/02/ac02f544-e07b-4cc5-a948-04e6a3c12f2b/estes_jonesdiner.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e5/2b/e52b1354-0dd2-4e9b-b310-ce66e4a834c5/estes_times-square2004.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/66/f366b1f6-be83-4ad5-a3d0-d5ef8c43e3a6/estes_portrait-of-i-m-pei.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e6/0c/e60c153e-4676-4384-8d42-f2460cf4a845/estes_towerbridge.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ab/2a/ab2a9e3b-d379-475d-ae34-3829094d5a5e/estes_water-taxi.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/56/305639b4-8792-494b-a298-11187bde7f06/richard-estes-courtesy-of-marlborough-gallery-new-york-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d8/71/d8713266-69aa-4cab-95e4-6c68cfa0deca/estes_beaverdam.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/41/eb/41eb7318-476c-45cb-bcfe-0cf2087b94b1/estes_bus-with-reflection-of-the-flatiron-building.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)