Why It Takes a Great Rivalry to Produce Great Art

Smithsonian historian David Ward takes a look at a new book by Sebastian Smee on the contentious games artists play

:focal(612x142:613x143)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9b/fa/9bfac264-2219-412b-b203-2b750b8274fd/snpg2004173picassorweb.jpg)

From an early age we’re told to be nice, play well with others, color inside the lines, and be cooperative and respectful to those around us. Yet it doesn’t take too long—high school or one’s first job—to realize that this ideal state of social harmony rarely exists in the world. And, that being nice may actually hurt you.

Indeed, rivalry seems to make the world go round.

Extrapolating from the personal, most theories of civilization, from Darwin (survival of the fittest) to Marx (class struggle) to Freud (psychologically killing dad), find the motor of history in competitive rivalry and the drive to conquer. Not just to win, but to win at the expense of your nemesis.

Even in the intellectual professions, the reality of life in the arts and sciences is not so much a tranquil arcadia of disinterested inquiry than a bear pit of conflicting agendas and egos. Tabloid-style gossip aside, the question of rivalry is not just intriguing from the perspective of individual psychology, but in the deeper relationship between the encounter with styles and ways of writing or seeing.

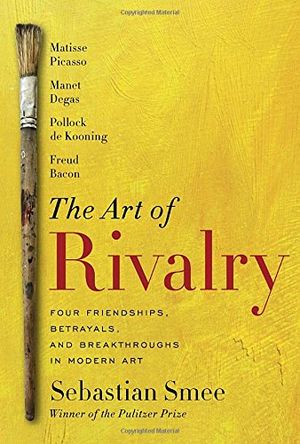

The Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Sebastian Smee, while not avoiding the personal, is interested in this larger question in his new book The Art of Rivalry in which he considers how the making of art develops and evolves out of the collision between rival artists. The pun in his title suggests that he’s interested in looking at the work that results from the personal and artistic relationships of his four pairs of modern painters: Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud; Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet; Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse; Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning.

Rivalry in the arts is probably worse than in any other profession given the subjectivity involved in judging who’s ahead and who’s slipping behind either among one’s contemporaries or in the eye of posterity. Artistic rivalries may indeed be more angry and feverish because most artists are sole practitioners—they work on their own, putting their own egos on the line, and are not protected, or repressed, by having to adhere to organizational and bureaucratic norms.

Success in the arts is so chancy and uncertain, and so dependent on one’s self, that it’s no wonder that writers and artists are always checking over their shoulders, preternaturally alert to slights and insults, and are quick to take offense at any threat. Money is important here: one’s livelihood is at stake in the jostling for sales, royalties and prizes.

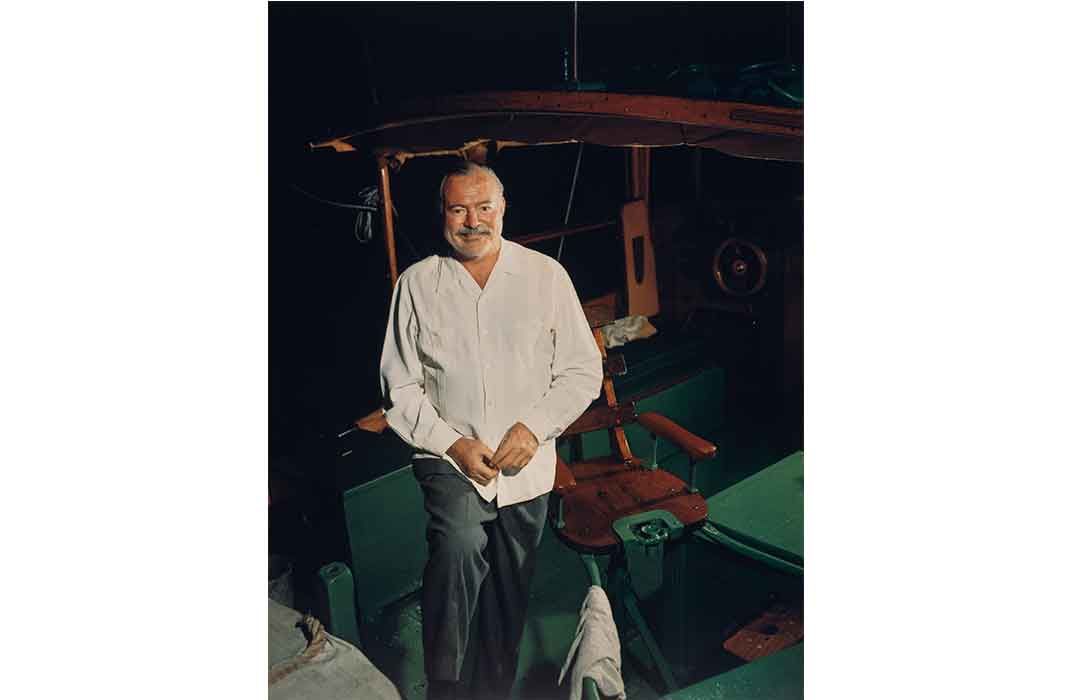

The most famous American case of naked egoism played out at the expense of his “colleagues” is undoubtedly Ernest Hemingway. “Papa,” as he liked to be called, always had to be the Daddy.

The one constant in his life and career was his willingness to viciously turn on his contemporaries and, especially, those who had helped him. Hemingway wrote muscularly about how literature was a boxing match in which he would “knock out” not just his contemporary rivals, but his literary fathers: Gustave Flaubert, Honoré de Balzac and Ivan Turgenev. Amidst all this personal mayhem, psycho-drama, and tabloid-style feuding, Hemingway’s boxing analogy actually contains the germ of a more interesting idea—the extent to which writers and artists are influenced by one another in creating their own work.

As masters of a prose style that he sought to emulate for his own time, Flaubert and Turgenev did influence Hemingway, despite his unpleasant braggadocio.

Tracing these genealogies of influence is a main task of literary and art history; it’s what Smee is doing, in a very accessible way, in his book. And it’s also the main task of academic scholarship. The literary critic Harold Bloom wrote an influential 1973 study called The Anxiety of Influence about how writers play off each other across time as they seek to assimilate the lessons and achievements of previous generations, while also implicitly trying to surpass their artistic mothers and fathers. At the Smithsonian Institution's National Portrait Gallery, aside from collecting art and artifacts for the permanent collections and for special exhibitions, my task as a historian there is to untangle the connections between artists and show the consequences of historical influences.

But the question of artistic influence becomes especially heightened, and perhaps especially rich, when it is played out between contemporaries, working through the problems of their art, either competitively or cooperatively, at the same cultural moment. F. Scott Fitzgerald did Hemingway the enormous service of editing the ending of the latter’s novel, A Farewell to Arms.

Ezra Pound, a great poet, but a strange and troubled man, never allowed his own ego to get in the way of his whole-hearted advancement and support of other writers, from T.S. Eliot to Robert Frost. Eliot dedicated his great poem “The Waste Land” to Pound, recognizing the American’s editorial role in shaping the poem. Pound’s generosity to others is perhaps rarer than we’d like it to be, but the question of the relations between contemporary artists remains a fruitful area of exploration to understand how art advances.

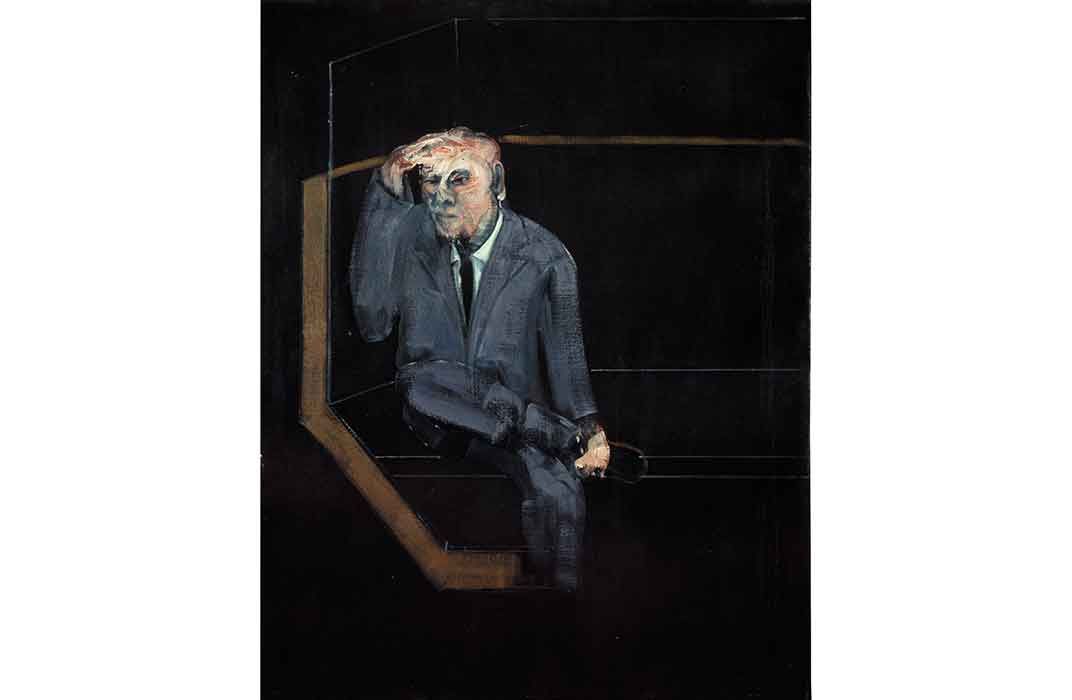

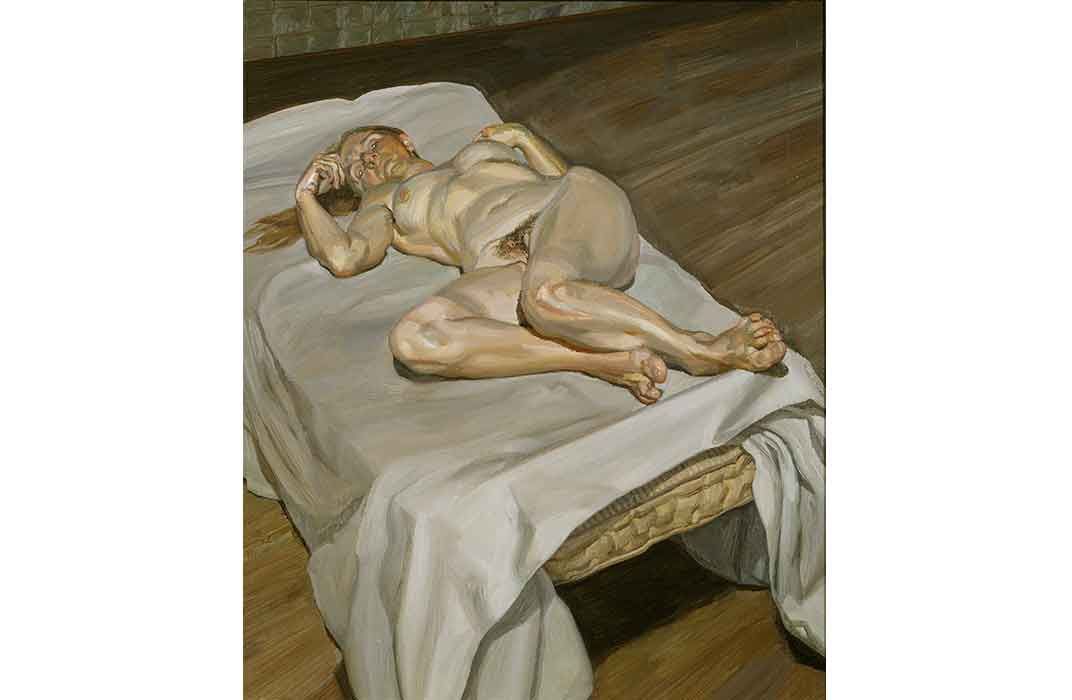

Of these pairings that Smee addresses, that of Bacon and Freud (a grandson of the psychologist) is probably most unfamiliar to an American audience. And in terms of artistic reputation, it is not quite evident that they are of the same stature of the others; important yes, but perhaps not world-historical in their influence. The Bacon and Freud relationship is, however, the most entertaining to read about, since Smee adroitly sets their relationship within the context of the wildly complicated London art scene that emerged after World War II.

You need an Excel spreadsheet to keep track of the personal relationships between friends, relatives, lovers (of both sexes), rent-boys, gangsters, disinherited aristocrats, and the mandarins of the English art establishment. There’s a lot of bed swapping and fistfights all played out against the serious work of art making for both Bacon and Freud. Bacon was slightly older than Freud and was the dominant partner in the relationship. It’s clear that Freud had a personal, but more importantly, an artistic crush on the older man. Conversely, Bacon was not adverse to having admirers but he recognized, as did many others, Freud’s talent.

Personal style and patterns of behavior (both artists loved to gamble) aside, what Freud learned from Bacon was to loosen up. Stylistically, the artists were poles apart at the start of their relationship. Freud’s was rigid, focused and based on intense looking and meticulous replication of detail. Bacon eschewed accuracy of detail for the sensuosity of thick layers of paint loosely applied to canvas. Under Bacon’s influence, Freud’s work became more free, more discursive, going after psychological or metaphoric, not actual, truth. It’s charming that the grandson of Sigmund Freud should overcome his repression through what amounted to artistic therapy. Despite their long relationship, Freud and Bacon eventually fell out, perhaps over money, perhaps because the younger man had become as successful as his master.

The generosity of Édouard Manet to Edgar Degas broke the younger artist out of the straightjacket of academic and history painting. When they met, Degas was laboring on large paintings on biblical themes that were taking him years to complete or, worse, abandon. Manet took Degas out of the studio and into the street, engaging him with modern life both emotionally and then stylistically.

In terms of the history of modern art, it is the Matisse and Picasso relationship that is central. The two men did not have the personal relationship that Smee’s other pairs had, although they knew each other. Instead, there is an element of pure artistic competition as the younger Picasso sought to assimilate the lessons of Matisse and then surpass him. Smee is excellent in how the expatriate American siblings, Gertrude and Leo Stein, incubated the origins of 20th-century modernism in their Paris salon, and in the choices they made in the artistic marketplace, favoring first Matisse and then the upstart Spaniard.

It is not altogether clear from Smee’s telling that Matisse realized how Picasso had set his sights on him; unlike the other encounters, it is a rivalry in which only one man was playing. But Smee writes about how Picasso was looking for a way out of the personal and artistic impasses of his early career—he was still very young during the now famous Blue and Rose periods—and found it in Matisse’s acquisition of a small African figure.

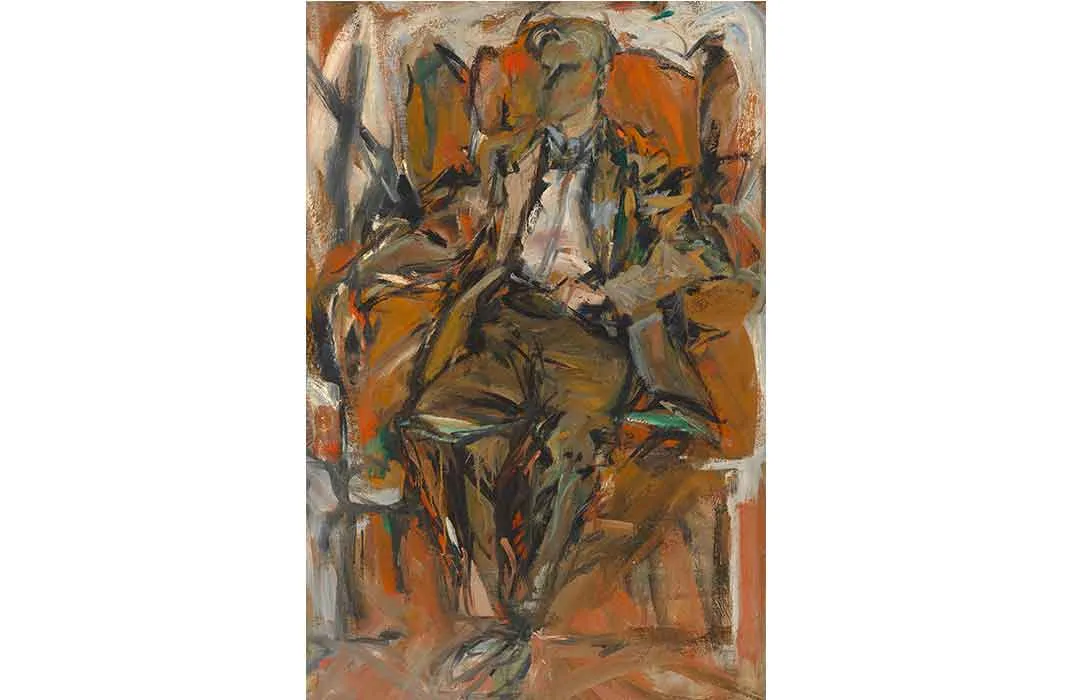

The Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock story is the closest to the Bacon and Freud narrative, not least because of the tempestuous personal lives of both men, especially Pollock whose personality problems caused him to become alcoholic and self-destructive. As with Bacon and Freud, de Kooning was an adroit, meticulous draftsman whose work was liberated by its encounter with Pollock’s drips and slashing lines of flung paint; de Kooning deserved his success but Pollock’s fall makes for horrific reading, ending, as it does, with his fatal car crash in 1956.

Smee is excellent in his speculation that Picasso initially resisted the vogue that Matisse, who was very much “The Master” of the Paris art scene, set off in Africaniana. But instead of just following, he eventually assimilated these “primitive” figures and then went beyond Matisse in his 1907 painting, Les Demoiselles de Avignon, a painting which combined the louche appeal of the bordello with the timeless masks of Africa.

Personally, the painting, marked Picasso’s declaration of independence; and he would go on in his long life and career to become the epitome of the modern artist. Artistically, it engendered the initial Cubist revolution that accelerated the 20th century’s artistic commitment to abstraction. More than the other pairings in The Art of Rivalry, the Matisse-Picasso relationship had crucial ramifications, not just for their two careers, but for the history of art; the others are interesting, important but not world historical.

Are there such rivalries today? It’s hard to know, living as we seem to be in an era of fragmented cultures in which the market place sets the public reputations of “our” artists and writers.

Is Damian Hirst in competition with Jeff Koons? Doubtful; except at the auction house. Locally and in small ways, though, in terms of the practice of art, creativity will always proceed in opposition to what came before—or in opposition to the poet or painter in the studio next door.

One of the secondary themes that emerges through Smee’s biographically grounded art criticism is how artists, previously invisible and unknown, come into our consciousness as influential and important. What looks inevitable—the rise of Freud or DeKooning; the emergence of Picasso—is as chancy and contingent as the personal encounters played out in the lives of artists.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)