Saying Goodbye to One of America’s Earliest Female Aviation Pioneers: Elinor Smith Sullivan

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/elinor1.jpg)

Amelia Earhart, the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic in 1928, comes to mind when talking about early flight—but a few other equally daring, though lesser known, female flyers of that era have stories to tell.

One of them, Elinor Smith Sullivan, whose career coincided with Earhart’s, died last week. She was 98.

Sullivan's aviation career got off to an early start. At age 7, the young Elinor Smith took lessons near her home on Long Island in 1918 with a pillow behind her back so that she could reach the controls.

From there, her career accelerated quickly. At age 15, Sullivan made her first solo flight. By 16, she was a licensed pilot. She was one of the earliest women to ever receive a transport aviation license, said Dorothy Cochran, a curator at the National Air and Space Museum. And in 1928, when she was just 17, on a dare set forth by a number of men who doubted her expertise, Sullivan flew underneath all four bridges along New York City's East River.

“She had all kinds of spunk,” Cochran said.

That same year, Sullivan set a women's solo endurance record of 13 hours, 11 minutes over Long Island’s Mitchel Field. When another female pilot broke that record, Smith reclaimed it the same year, staying in the sky for 26 hours, 21 minutes.

In 1929, she was named the best female pilot in the country, beating out Earhart and joining the ranks of famous pilots like Jimmy Doolittle.

The following year, she became a correspondent for NBC radio, reporting on aviation, and covering the Cleveland Air Races. She also took up a pen and became the aviation editor of Liberty magazine, and wrote for several other publications, including Aero Digest, Colliers, Popular Science and Vanity Fair.

Her flying career took a hiatus in 1933, when she married New York State Congressman Patrick Sullivan and started a family. The couple eventually would have four children.

(Sullivan was, however, the only female flier to be featured on a Wheaties Cereal Box, in 1934).

The former female flyer might have faded from the spotlight after her marriage, but some two decades later, after her husband's death in 1956, Sullivan was back in the pilot's seat. She flew until 2001, when she took one last flight at age 89 to test the C33 Raytheon AGATE at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia. Sullivan was also an important aviation advocate, working tirelessly in the 1940s and 50s to save Long Island’s Mitchel and Roosevelt Fields, where she had flown as a child.

Her autobiography, Aviatrix, published in 1981, and her induction into the Women in Aviation International Pioneer Hall of Fame in 2001 have kept her legacy alive—and in the 2009’s film Amelia, actress Mia Wasikowska played the young Sullivan.

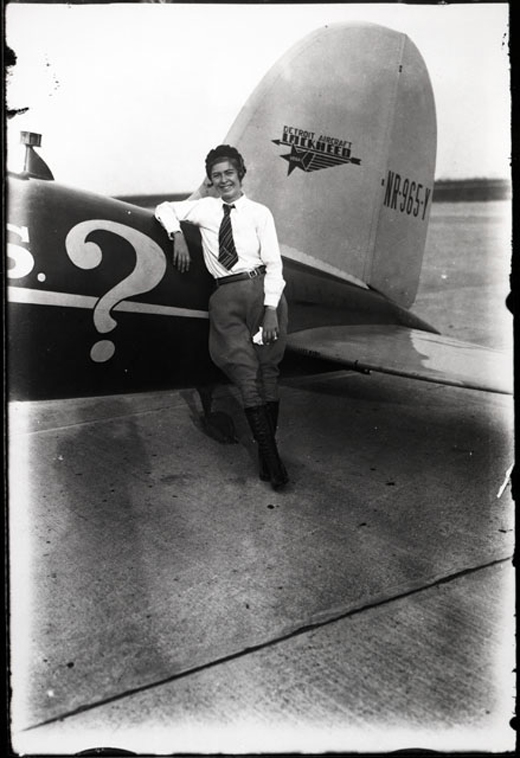

Her legacy and role in aviation is being recognized at the Air and Space Museum this spring. During the next few weeks, visitors to the museum will get to see an obituary plaque at the entrance to the building, remembering Sullivan’s contributions to aviation. A picture hanging next to it will capture her on top of a Lockheed Vega airplane, when she was happiest: preparing to take to the skies.

Read about more famous female aviators, including Pancho Barnes, Bessie Coleman and Jacqueline Cochran, in our photo essay.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)