The Scandalous Story Behind the Provocative 19th-Century Sculpture “Greek Slave”

Artist Hiram Powers earned fame and fortune for his beguiling sculpture, but how he crafted it might have proved even more shocking

:focal(546x30:547x31)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cd/71/cd71c69c-417b-4744-a627-aff8256a59c7/powers_gree_slave-web.jpg)

Karen Lemmey, sculpture curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, knew she was making a bold move.

In the museum’s recently opened exhibition, Measured Perfection: Hiram Powers’ Greek Slave, she installed the artist’s 1849 patent application to protect his famous artwork Greek Slave from illegal duplication, juxtaposing it with a video clip of museum staff 3D-scanning Power’s artwork. She did it, after all, at a building that was once the U.S. patent office, but the scan will allow the museum to print out a full-scale replica of the artist’s work.

“Powers was fiercely protective of his artwork, and he was concerned with competition,” Lemmey says of the American artist, who lived and worked for much of his life in Florence, Italy. Scanning a model of his work, which could then be printed on-demand, represents “Powers’ worst fear,” Lemmey admits. “On the other hand, I think he was so clever and so committed to using whatever worked best for his production that he would have been interested in 3-D printing and 3-D scanning,” Lemmey adds.

Powers applied for the patent, the exhibition makes clear, because the artist hoped to “control the explosion of knockoff replicas and unauthorized images.” Both the patent and the video appear in a show that focuses on the processes and techniques that Powers used to create the plaster model—depicting a nude, shackled woman—and then the steps he employed in his workshop using the latest technological tools of the time, to carve six marble Greek Slave sculptures, which he sold to prominent patrons.

Several of these nude sculptures toured the United States from 1847 to the mid-1850s with stops in New York, New England, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Louisville, St. Louis and New Orleans—drawing such large crowds that Greek Slave became “arguably the most famous sculpture of the 19th century,” says Lemmey.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ea/35/ea3525a0-bab9-456c-9255-d10b0a6902b8/ht008505web.jpg)

The highly provocative stance of the female figure, which Powers described as a Greek woman stripped and chained at a slave market, was seen as so salacious that men and women viewed it separately. Though it addressed the 1821-1832 Greek War of Independence from the Ottoman Empire, abolitionists seized on it as social commentary on the highly volatile subject of slavery in the United States.

“People sit before it as rapt and almost as silent as devotees at a religious ceremony,” reported the New York Daily Tribune in 1847. “Whatever may be the critical judgment of individuals as to the merits of the work, there is no mistake about the feeling which it awakens.”

“It was sensational and scandalous. It was the first time many Americans had ever seen a sculpture of a nude female figure,” says Lemmey. Unauthorized copies were manufactured and sold, prompting Power’s patent application.

The exhibition, not only contextualizes the artist’s work with the help of 3D printing, but also introduces new scholarship; Powers may have used an aesthetic shortcut, using life casts instead of modeling parts of his sculptures—a scandal akin to a discovery that Leonardo Da Vinci used tracing paper.

The show’s focus is the plaster cast dated March 12, 1843, and made from the artist’s clay model. It is described as Powers’ “original” Greek Slave. As nice as it would have been to feature one of the marble sculptures in the exhibition, the piece is a challenge because of its age and fragility to move from one museum to another, according to Lemmey.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dd/89/dd893cff-a1a7-4874-b206-3fa63763316b/untitledweb.jpg)

“I think, in some ways, if we had the actual Greek Slave in marble, as delightful as it would have been, it would have kind of stolen the show,” she adds. “It’s hard to look at process when you’re looking at the finished work of art. This is giving you the opportunity to look at how something is made and then to go back and appreciate the finished work.”

The artist’s process included a fascinating measuring device called a “pointing machine,” a tool that is variously dated to the 18th century, or even as far back as ancient Rome. The machine allowed sculptors to use several adjustable “arms” and pointers to measure the contours of the prototype and transfer them to a block of marble stone.

Lemmey describes Powers’ creation process as the envy of European artists, “which says a lot because there was quite a bit of anxiety about what America could produce culturally,” she adds. In addition to charting the process Powers used to make the sculpture, the exhibition examines a time when a rising American collector class was making the voyage to Europe more frequently.

“They are building wealth, which puts them in a position to buy. So when you get to Florence as an American tourist, and you see a fellow American who’s really done right by himself, you are in a sense making a patriotic statement by buying his work and bringing it back to the United States. So Powers is, in a lot of ways, a cultural ambassador.” Powers’ studio was a must-see on the Grand Tour and was even listed in travel guides of the period.

That cultural ambassadorship came from a man, who identified as 100 percent American, and whose wife couldn’t wait to return to Cincinnati, where she grew up, to raise her children there. “He is keenly aware that he is raising American kids in Florence,” Lemmey says. (When Nathaniel Hawthorne visited Powers in Florence in 1858, he noted that Powers “talks of going home, but says that he has been talking of it every since he first came to Italy.”)

Perhaps precisely due to his distance from his homeland, Powers was able to tailor his Greek Slave, which interestingly appealed to both northern and southern audiences, to the fraught politics of the day—the divisive period leading up to the Civil War.

“He’s capitalizing on an American interest in slavery in general,” Lemmey says. “This composition was [acquired] by both Northern and Southern collectors. It sort of underscored the abolitionist sentiment, but also somehow resonated in a way with certain collectors in the South.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/95/c4/95c4c980-bf4d-47bd-acdf-5674c64bae10/untitled2web.jpg)

Still Relevant

Charmaine Nelson, associate professor of art history at McGill University who has studied Powers within the context of race theory and trans-Atlantic slavery studies, sees things quite differently. Greek Slave enjoyed a “rather extraordinary reception on both sides of the Atlantic” and became “the iconic neoclassical work of the 1840s,” and the sculpture remains relevant today for Powers’ ability to “cleverly speak to the topic of American slavery indirectly, to create a fantastically popular sculpture that was accepted by multiple and complex publics.”

But, Nelson adds, he missed an opportunity.

“Powers’ decision to represent his slave as a white, Greek woman in the midst of the political turmoil of American slavery, speaks to the supposed aesthetic impossibility of the black female subject as a sympathetic and beautiful subject of American ‘high’ art of the time,” she says.

“If one looks at the landscape of black female subjects in neoclassical sculpture of the era, we see not the absence of black female subjects as slaves, but their absence as beautiful subjects rendered in compositions which produced narratives that called for the dominantly white audience to view them as equals and/or as sympathetic victims of slavery.”

Having located his slave in a Greek and Turkish context, then, Powers allowed his mostly white audience to determine whether it wanted to read an abolitionist narrative onto the work. “At the same time,” Nelson adds, “the work more sinisterly inverted the colonizer-colonized relationship, representing the sexually-vulnerable and virginal slave woman—the locket and cross on the pillar are symbolic references to her character—as white (Greek) and the evil enslavers and rapists as men of color (Turkish).”

White audiences’ choice to avoid confronting slave-owning practices may have been responsible for the sculpture’s popularity in the South, Nelson says. And, Powers’ agent Miner Kellogg, who created a pamphlet to accompany the works on their American travels, may have also helped frame the work for audiences that would have otherwise rejected it.

“If one looks at Powers’ personal correspondence, we can see the way he shifted over time from a rather ambivalent opinion about slavery to being a strident abolitionist,” Nelson says. “I think that his distance from America in these critical years allowed him to question the normalization of slavery in the United States.”

New Scholarship

If viewers of the day had known of Lemmey and her colleagues’ research, the artwork would have been widely criticized. Powers may have repeatedly committed the artistic equivalent of plagiarism: using “life casts,” sculptures made from molds of body parts.

A life cast of a forearm and hand that exactly matches the left arm and hand of Greek Slave in the show prompts the question of whether or not the artist crossed a boundary. “Modeling in clay and body casting was strictly observed,” a label discloses, “sculptors risked their reputations and credibility if they were suspected of ‘cheating’ by substituting a body cast instead of modeling the figure themselves.”

“You’ve taken a shortcut that you ought not to have. You are not modeling it from the sketch; you are way too close to the original,” Lemmey says, noting several life casts in the exhibition, from a cast of Powers’ daughter Louisa (then aged six months) to a hand that, if rotated, fits the “Greek Slave” plaster cast like a glove.

“He would have been absolutely eviscerated by critics if they understood what this is suggesting.”

But, she adds, few if any patrons were probably privy to the casts. “We don’t know how much behind the scenes we are looking at. That’s part of the fun of this exhibition.”

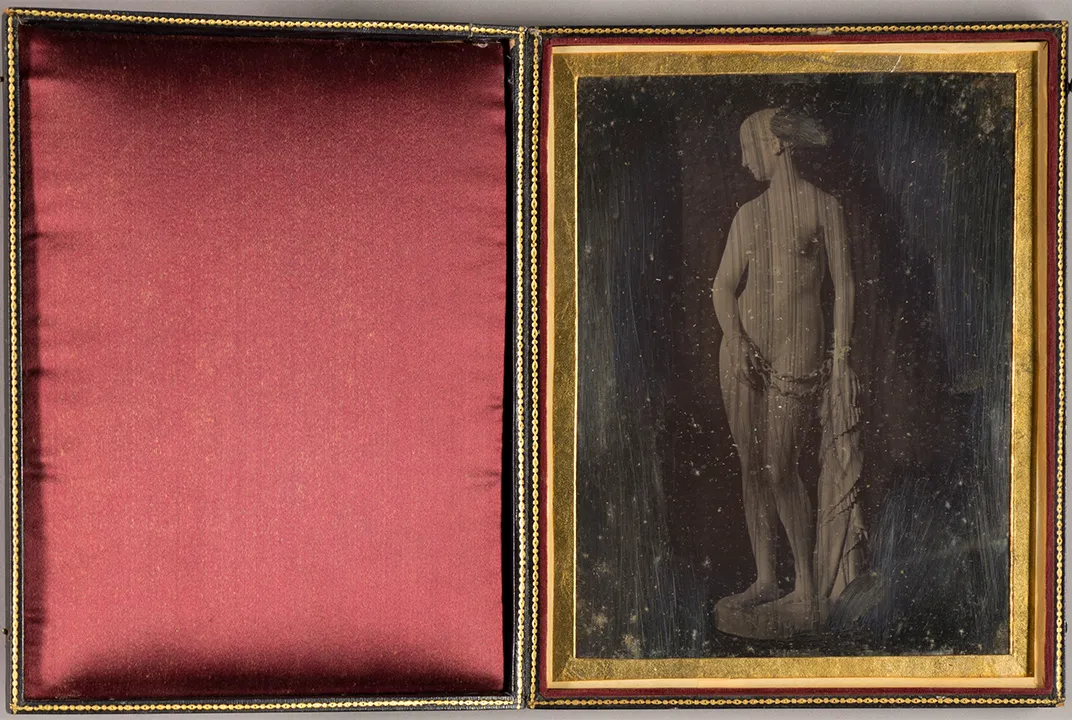

Another gem in the show is a daguerreotype of one of the six marble sculptures, which Lemmey believes represents the version of the sculpture that was purchased by an English nobleman and subsequently destroyed in World War II.

“This may be the only visual record of that sculpture, which makes the daguerreotype all the more important,” says Lemmey of the image, which was in the collection of Powers’ agent Kellogg, who organized the Greek Slave tour of the United States.

“I love the idea that this has a really rich provenance of being made in front of an object, possibly in Powers’ presence, passing from the artist directly to his agent, who is also an artist, and then descending in the Kellogg family and then purchased by this individual giving it directly to the museum,” Lemmey says. “Imagine if a daguerreotype is the only standing record of a sculpture that’s gone forever.”

Measured Perfection: Hiram Powers’ Greek Slave is on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. through February 19, 2017. Home to more than 100 other works of Powers’ on exhibit and held in open storage, the museum also has an exquisite three-quarter size version of Greek Slave on its second floor. On November 13, when the Renwick Gallery re-opens after extensive renovations, a full-size 3D print of Greek Slave will go on display in the Octagon Room, created from a scan of the American Art Museum’s original plaster cast—the focus of the current exhibition. The National Gallery of Art, which recently acquired a full-size marble sculpture of Greek Slave from the Corcoran collection, says it will put the marble sculpture on view by spring of 2016.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)