Scientists Are Using This Collection of Wood Samples to Combat Illegal Logging

Archie F. Wilson loved wood enough to amass the country’s premiere private collection. Now scientists are using it as a weapon against illegal logging

If his wood collection is any reflection of his character, Archie F. Wilson (1903-1960) was a meticulous man, tenacious in the pursuit of scientific precision yet compelled by beauty. During the day, he served as a manager at various industrial companies, but in his free time, Wilson collected, curated and documented what the Smithsonian Institution calls the “foremost private wood collection in the United States.”

Today, those 4,637 samples of wood from all over the world—the Wilson Wood Collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History—are at the forefront of the global fight against the illegal wood trade. Scientists are using Wilson’s collection, along with samples from others around the world, to create the Database, or the Forensic Spectra of Trees (or ForeST) database, of wood’s many chemical fingerprints. The types of wood being tested include species designated as endangered by CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

The ForeST Database and the technology the collection complements, DART-TOFMS (Direct-Analysis in Real-Time Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry), will provide a powerful tool for customs agents, law enforcement, the judiciary, lawmakers and others grappling with the environmental, cultural and economic devastation caused by illegal logging and trade in precious hardwoods and timber. The United Nations and Interpol estimate this trade costs the global economy up to $152 billion a year—more than the annual value of trafficked ivory, rhino horn, birds, reptiles and corals combined.

The DART instrument applies a stream of heated helium ions onto the sample and quickly provides a full chemical profile. The person testing the wood—a customs agent, for instance—simply has to hold a tiny sliver of wood in front of the ion beam to generate an analysis. It’s noninvasive, requires very little preparation and works nearly instantaneously if the sample in question is included in the database.

Cady Lancaster, a post-doctoral fellow and chemist, is one of the scientists working on the joint research venture between the World Resources Institute and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Forensics Laboratory.

“For me, this collection is really priceless because without [it], there would be no way to continue to work on this project and combat wildlife trafficking and especially deforestation,” she says. “Timber trafficking is so prolific and global. A single wood collection, like the Wilson, can provide samples from dozens of countries and hundreds of timber stands in a single location. Without that representation, we would not be able to carry out a project of this magnitude.”

Samples from the Wilson Wood Collection are among hundreds of rarely-displayed specimens on view in the exhibition “Objects of Wonder,” currently on view at the Natural History Museum. The show examines the critical role that museum collections play in the scientific quest for knowledge.

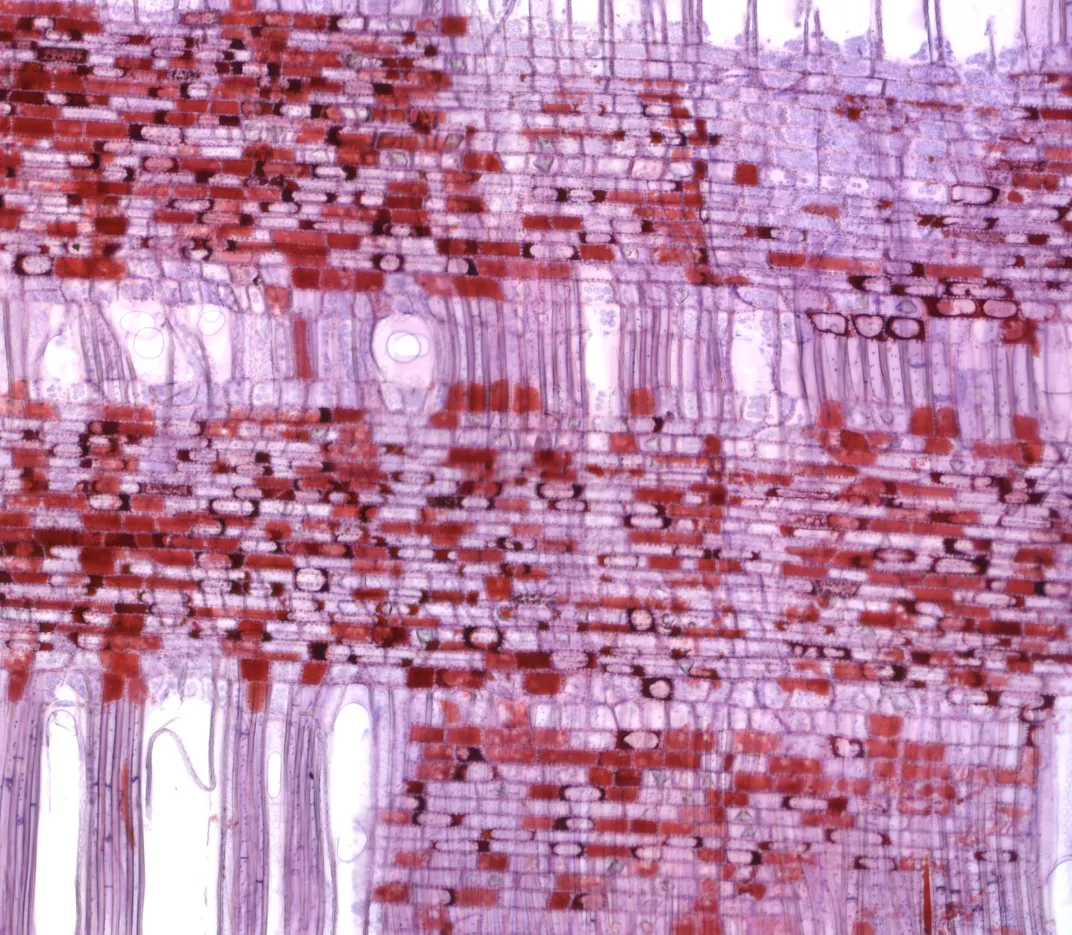

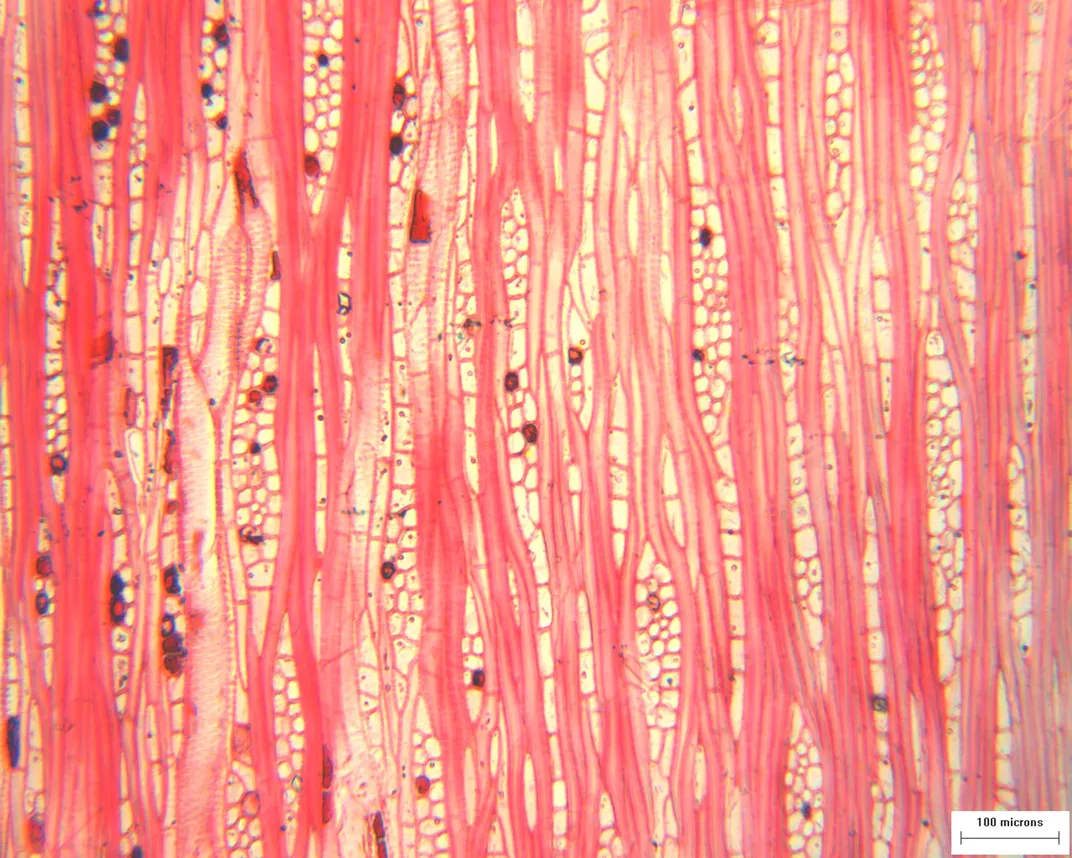

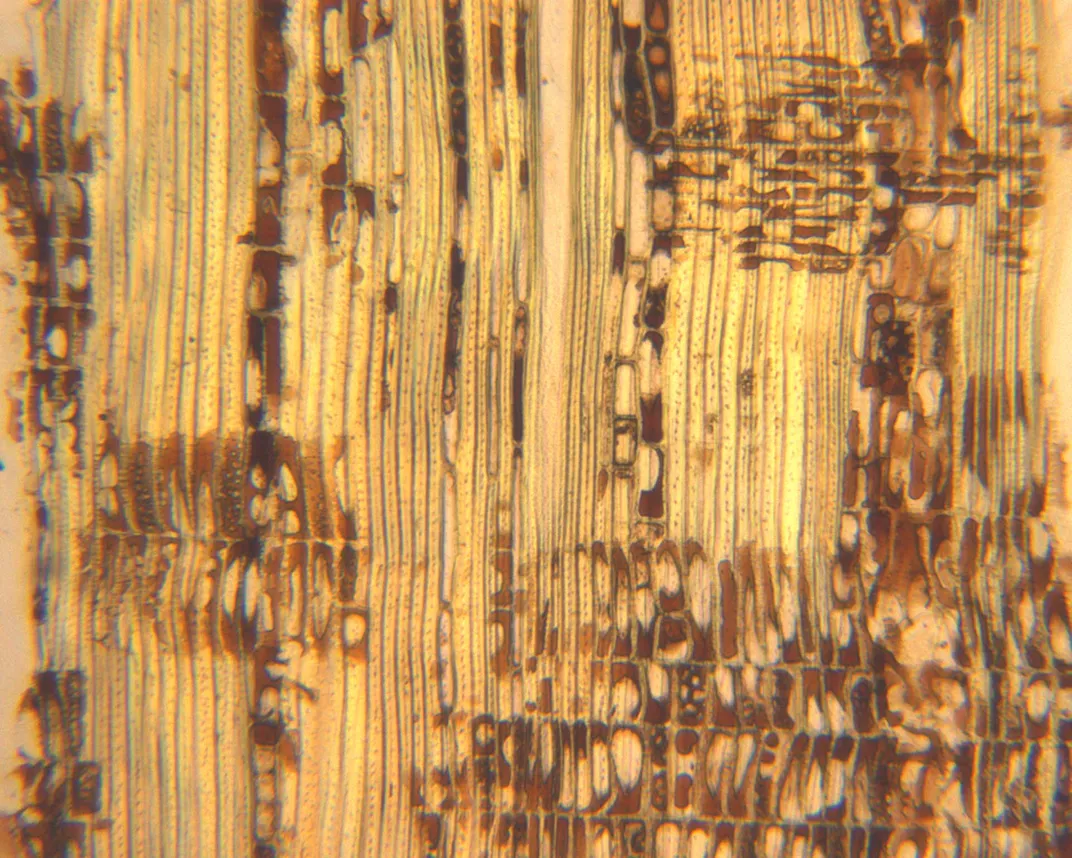

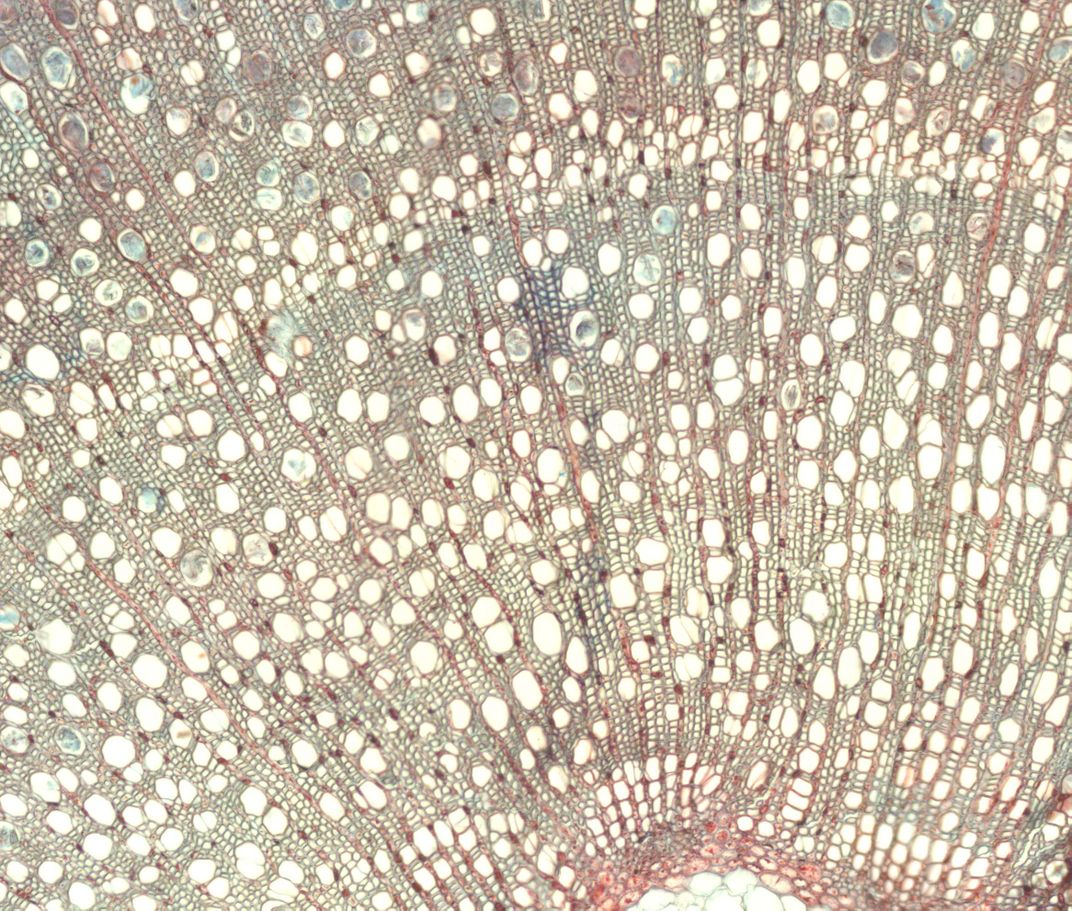

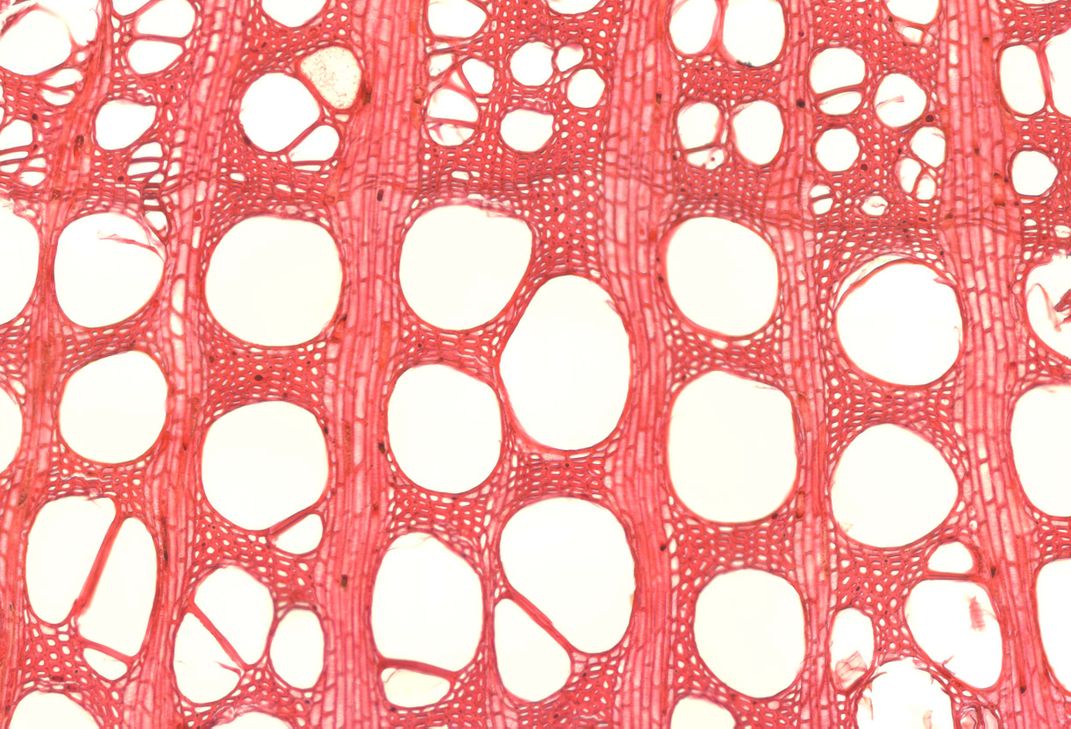

The wood, which is presented as slides prepared for a microscope, is otherworldly, its patterns and hues as unexpected and provocative as abstract art. Through this lens, a sample of Cornus stolonifera, commonly called red osier dogwood and found across North America, resembles a stained-glass window, its geometric pale cells fanning upward between diaphanous red threads.

During the 1950s, Wilson was a research associate studying wood at the Chicago Natural History Museum, and between 1940 and 1960, he served in leadership roles with the International Wood Collectors Society (up to and including president). He was a rigorous archivist; each sample in his collection, which came to the Smithsonian in 1960, is cut to about seven-by-three inches and beautifully sanded, says Stan Yankowski, a museum specialist in the museum’s department of botany. Specimens are stamped with the wood’s name, and Wilson maintained four cross-referenced card files designating family, genus and species, a number file, and common name.

Of the 43,109 wood samples in the museum’s collection, Yankowski says Wilson’s is the largest donation from a private collector. Cady Lancaster says she worked with about 1,600 samples from the collection and, in an effort to make the database comprehensive, is currently traveling the world in search of additional samples.

“Reliable wood identification is one of the fundamental challenges facing efforts to control illegal logging and associated trade,” says Charles Barber, director of the WRI’s Forest Legality Initiative. “If we don’t have basic information about species and geographical origin of suspected wood, it is difficult to detect, prevent or prosecute illegal loggers and traders.”

“DART-TOFMS is among the most promising new technologies for wood identification with respect to accuracy, cost and methodological simplicity,” says Barber. “Like other approaches, however, practical applications of DART-TOFMS for both law enforcement and supply chain management require development of a reference sample database, which is a priority for WRI’s work on this.”

The DART method can also be used to determine information about a wood’s geographic source and complements identification techniques such as DNA testing, stable isotope analysis and wood anatomy analysis.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection operates three DART instruments (costing between $200,000 to $250,000) in ports now, Barber says, but they are currently used to test other commodities. Once agents receive training, they can begin testing wood at ports and borders, where billions of dollars of illegal timber continue to enter the United States.

Like any precious commodity that is rare or endangered, wood has become the focal point of a global black market that seeps through porous international borders and defies law enforcement and conservation managers. The relentless search for rare species devastates whole ecosystems and the animals and cultures that depend on them.

“Illegal logging and associated trade is a cause of forest degradation, and is often a catalyst for complete conversion of forests to agriculture or degraded wasteland,” Barber says. “It also robs communities and governments of revenue, breeds and feeds corruption, and is increasingly linked to transnational criminal networks and trafficking in wildlife and arms, with a growing online presence.”

In China, for instance, rosewood—known as Hongmu and under CITES protection since 2013—is used to build high-end Ming and Qing dynasty replica furniture. Consumer passion for the material is fueling a bloody yet profitable trade in Asian countries where stands of the trees remain. Several species are already commercially extinct, according to the Environmental Investigation Agency.

Illegal logging accounts for between 15 and 30 percent of all wood traded globally. Up to 61 percent of all timber production in Indonesia is believed to be illegally traded, according to the World Wildlife Fund, and in Russia, 25 percent of timber exports derive from illegal logging.

In an effort to stem illegally sourced wood entering the United States, Congress amended the Lacey Act, first passed in 1900 to stop imports of poached wildlife, in 2008. The bill now includes plants and is the first legislation of its kind in the world. In a 2015 progress report, the Union of Concerned Scientists found that illegal timber imports into the U.S. declined between 32 and 44 percent, although the group noted that in 2013, illegally-sourced wood still accounted for imports worth $2.3 billion.

This wood, and the environmental and economic consequences of its harvesting, can land right at the feet of unsuspecting American consumers. In 2015, the flooring company Lumber Liquidators admitted to violating the Lacey Act by importing illegally sourced hardwood from Russia—the timber came from forest habitats critical for the few hundred Siberian tigers still living in the wild.

In February, the WRI, the U.S. Forest Service, the World Wildlife Fund and the Center for International Trade in Forest Products invited scientists, law enforcement officials and regulators to participate in the Seattle Dialogue on Development and Scaling of Innovative Technologies for Wood Identification. Attendees agreed that one of the fundamental problems facing the field was the difficulty of verifying a species and its geographic origin.

“The trade in rosewood—an entire genus put under CITES regulation in October 2016—is a perfect example,” the executive summary noted. “With over 250 species in the genus—many of which are indistinct and have a long list of lookalikes—trying to determine the risk or vulnerability of each species is a daunting, expensive task. . . . Improving credible and practical methods for identifying rosewood species is, therefore, a very real and pressing challenge for CITES and its member governments, in combating a large and growing illicit trade tied in many places to organized crime and violence, due to the very high value of rosewood timbers.”

Thanks to emerging technologies, the collection that Archie F. Wilson treated so studiously is finding a new purpose as an accessible source of thousands of invaluable tree samples.

“By housing and curating vouchered specimens and allowing researchers to access them,” Barber says, collections like Wilson’s are supporting an international effort to combat a crime that crosses borders, cultures, ecosystems and generations.

A sampling of the Wilson wood collection is currently on view in the exhibition "Objects of Wonder" through 2019 at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/WendyClarke1.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9b/5b/9b5b1fd5-5ba2-4fd2-a0c8-abce5402a542/cornus_controversa_c_hqedit.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0f/65/0f6501aa-a576-4f4b-8c43-9857194083e4/picea_pungens_transverse3_hqedit.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/WendyClarke1.JPG)