Scientists Race to Salvage Fossils Before Panama Canal Expansion

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/panama-canal-excavations.jpg)

There was a time when North and South America did not share a land border. Instead, a large river separated the two land masses. The animals and plants on the continents kept to themselves mostly, with the exception of the birds that refused to call any one place home.

Then, 15 million years ago, the North and South collided, volcanoes erupted and the Atlantic was separated from the Pacific. About 12-million years later, a land bridge formed between the two continents, and the animals and plants began to travel freely.

This land bridge formation occurred near the site of today's Panama Canal, which makes the area an attractive site for paleontologists who want to learn the continental origins of individual species. Thousands of fossils, ripe for analysis, lie in the canal walls. But the scientists who want them must act fast. The Panama Canal widening project, due to be completed in 2011, has already removed 10-million cubic meters of earth, with more to come.

Smithsonian researchers are now trying to stay one step ahead of the bulldozers. Working in collaboration with the University of Florida and the Panama Canal Authority, the scientists move in, following dynamite blasts, to map and collect fossils. As of last July, 500 fossils, from rodents, horses, crocodiles and turtles, some dating back 20-million years, have been uncovered.

"We expect the fossils that we have been salvaging to resolve some major scientific mysteries," says Carlos Jaramillo, a Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute scientist. "What geological forces combined to create the Panama land bridge? Was the flora and fauna in Panama before the land bridge closed similar to that in North America, or did it include other elements?"

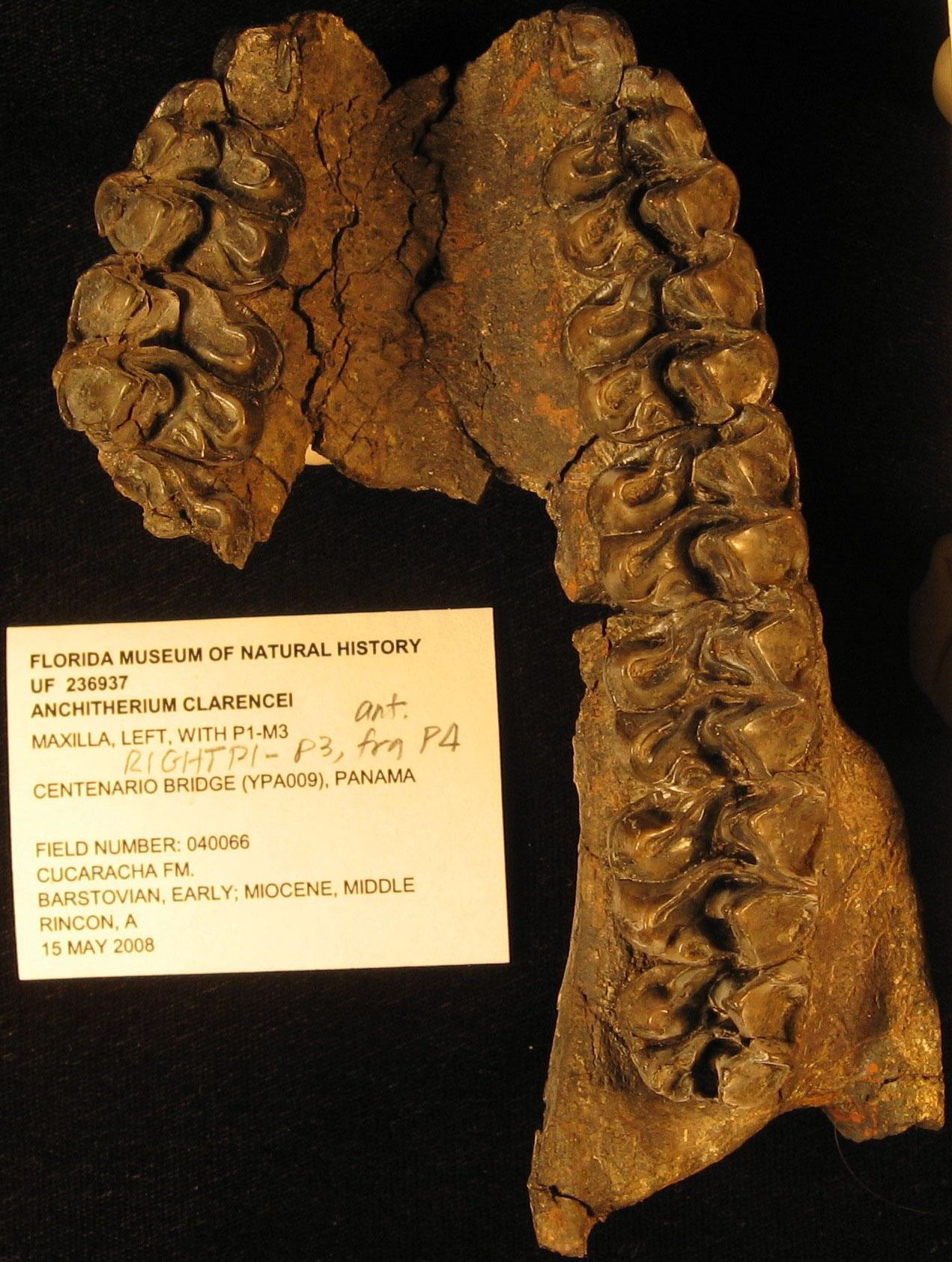

At least one answer to Jaramillo’s second question has already been found. Aldo Rincon, a paleontology intern, unearthed a set of fossilized chops belonging to the three-toed browsing horse, known to have grazed in Florida, Nebraska and South Dakota between 15-to-18-million years ago.

According to Beth King, the Institute's science interpreter, (who was recently featured in a Scientific American podcast), the presence of this horse in Panama significantly extends the southern tip of its range from previous finds, supporting the hypothesis that the habitat was probably a mosaic of relatively dense forest and open woodlands.

There are many more fossils to be found at the Panama Canal widening site, and King expects there to be many papers published within the next five years regarding their significance.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-caputo-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-caputo-240.jpg)