The Scopes Trial Redefined Science Journalism and Shaped It to What It Is Today

Ninety years ago a Tennessee man stood trial for teaching evolution, a Smithsonian archives collection offers a glimpse into the rich backstory

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/5e/295eade2-a7d8-4621-9d46-af422f36e6dc/sia20070124web.jpg)

Dayton, Tennessee, was just a blip on the map when a small group of businessmen and civic leaders hatched a plan to bring publicity and much-needed commerce to their sleepy little town; all they needed was some help from a local teacher. They invited him to meet at a downtown lunch joint, and from there the plan spun rapidly out of control. Their scheme turned the teacher into a martyr of contrivances and made a national spectacle of the town they had hoped to lift from economic doldrums.

The story of the “Scopes Monkey Trial,” the country’s first legal battle over the teaching of evolution, began in April, 1925, when a Dayton businessman read an advertisement placed in a Chattanooga newspaper by the recently established American Civil Liberties Union. The ad promised legal assistance to anyone challenging the state’s new Butler Law, which banned the teaching of evolution—specifically, “any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals."

John Thomas Scopes was Dayton’s high school football coach and substitute biology teacher. Portrayed today as a hero of great conviction, Scopes did not specifically recall teaching evolution. He did, however, believe the law was unjust, and the town leaders were able to persuade him to stand trial for their cause, although their cause had little to do with evolution. Their aim was simply to draw visitors and their wallets into town for the trial.

The men’s PR instincts were right, if misguided. The State of Tennessee v. John T. Scopes brought two of the most charismatic public orators in America to Dayton. The famous criminal defense attorney, Clarence Darrow, arrived to defend Scopes, and three-time presidential candidate Williams Jennings Bryan stepped up as the prosecuting attorney.

The trial, which took place from July 10 through July 21, 1925 (Scopes was charged on May 5 and indicted on May 25), quickly evolved into a philosophical debate between two firebrands about evolution, the bible and what it means to be human. Radio and newspaper reporters flocked to Dayton; spectators crowded the courthouse; and food vendors, blind minstrels, street preachers and banner-waving fundamentalists fueled the carnival atmosphere. A performing chimpanzee was even employed to entertain the crowd as a mock witness for the defense. Political cartoonists, newspaper journalists and photographers captured the town in all its theatrics.

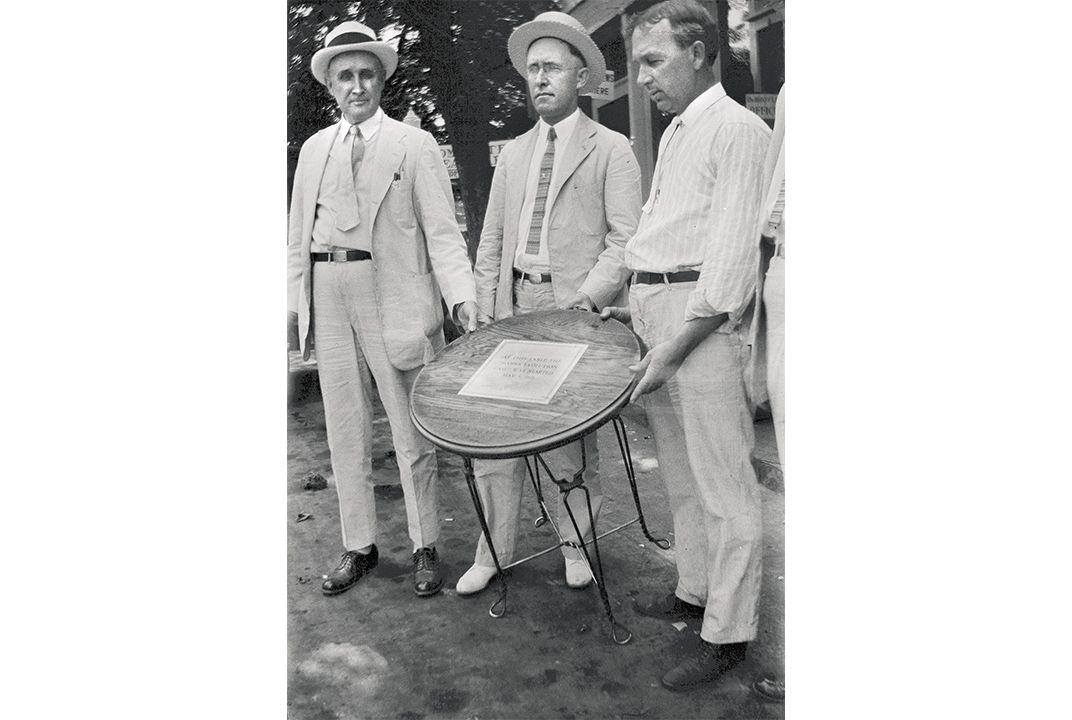

In one photo, as if in testament to the success of the town’s publicity stunt, three men stand posing behind a small round table. On the table is posted a sign that reads:

“At this table the scopes evolution case was started May 5, 1925.”

Perhaps the men had not quite grasped the extent to which Dayton was being ridiculed around the country as a reservoir of ignorance and zealotry.

Taken by local college student William Silverman, the photo is among many that have been added to the Smithsonian Institution Archives in the past decade, long after historians thought they had seen everything there was to see relating to the Scopes trial. It provides a glimpse into the rich back story of the trial and its surrounding events. The photo was donated after the archives posted a collection of new images discovered by historian Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette. A research associate at the Archives, LaFollette says hidden gems like these occasionally come to historians when people have the foresight to preserve original materials.

She knows about hidden gems. In 2006, she had been researching a book on the history of science in radio when she found a box in the collection from journalist Watson Davis. He was the managing editor of Science Service, a syndicated news wire providing stories on science to the media. Science Service’s records constitute one of the largest collections in the Archives, but the box LaFollette found had been tucked away unprocessed. She says it was an unorganized hodge-podge of photos and documents that looked like they had been packed at the last minute, quickly and randomly before being sent to the Smithsonian.

But within those documents was a treasure trove of history, including an undiscovered envelope of Scopes trial photos and documents. One series of photographs in particular is exciting for the unique perspective Davis was able to capture. It was taken from an angle no one had seen before. “In his camera lens you can see the back of Clarence Darrow, and you can see the face of William Jennings Bryan,” LaFollette says. “You have the drama of the moment of confrontation between these two great figures in American history. In many ways, it’s as if you had a photograph of the Lincoln-Douglas debates.”

LaFollette, an expert on the history of science in the media, says those photographs led her to dig deeper into the collections and to piece together more of the story behind the trial. The Davis material provided fodder for another book: Reframing Scopes: Journalists, Scientists, and Lost Photographs from the Trial of the Century.

Among other things, the records provided a window into the fledgling field of science journalism at the time. Science Service had been founded just a few years earlier, and the trial was the first real test of the journalists’ ability to cover a complex, controversial scientific topic in a way that a public audience could understand.

Today, science is regularly covered in the news media, but at the time, scientific subjects were mostly conveyed through dedicated science magazines and newsletters written by scientists for scientists. The idea of newspaper writers bringing a greater understanding of science to the general public through their medium was a new paradigm.

“They were paving the way for what science journalists do today,” LaFollette says, though in many ways Davis’ documents reveal a much more fluid line between reporting and collaborating than most would accept now. “None of the other historians who had written about the trial knew the extent to which you had these journalists behind the scenes doing things,” LaFollette says.

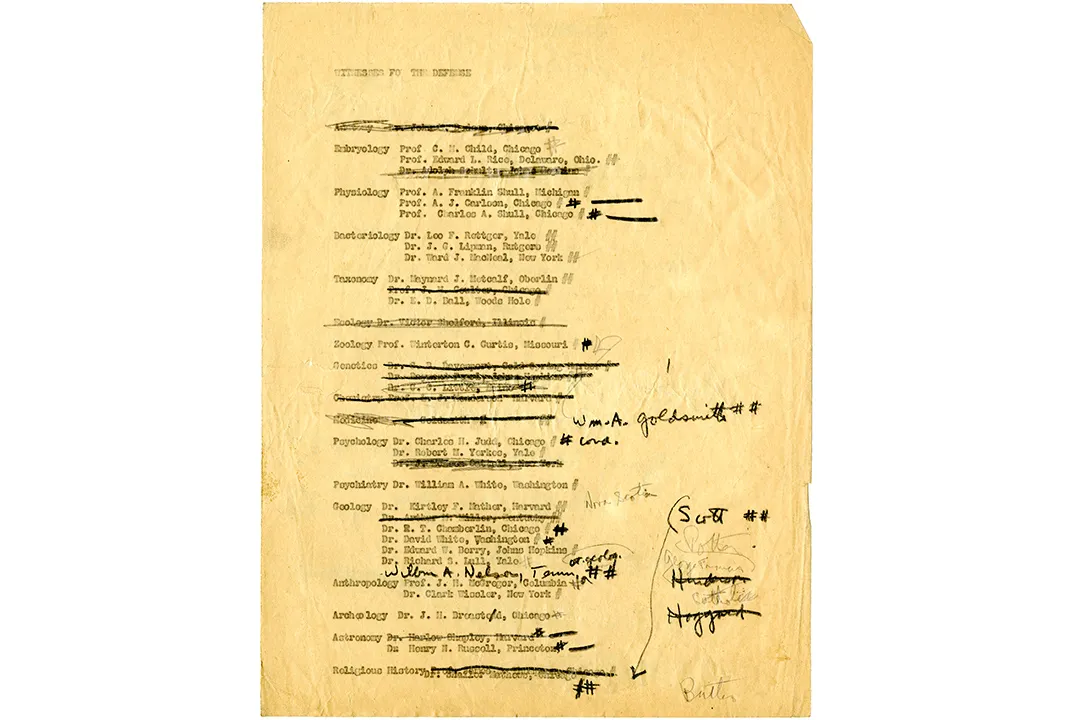

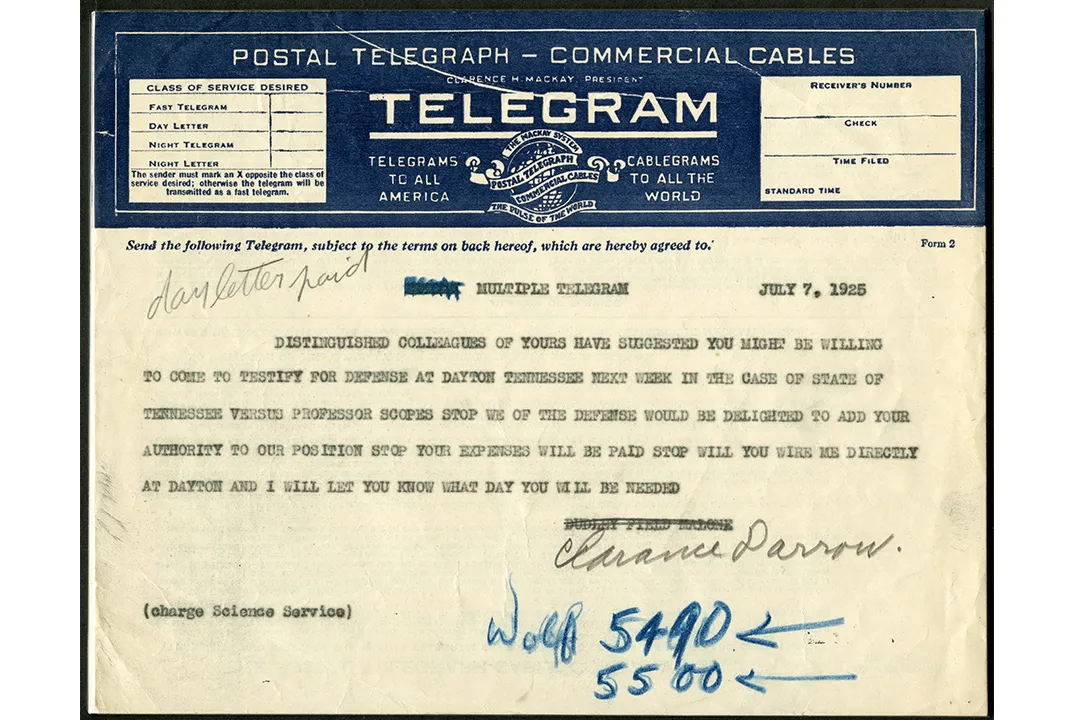

For example, Watson Davis took charge of lining up expert witnesses for the defense. On his train ride from Washington to Dayton, he telegraphed a list of scientists to Darrow and his defense team instructing them to invite the scientists to testify. He also took it upon himself to send the invitations, signing them at first with the name of one defense attorney, Dudley Field Malone, and then later changing the sender to Clarence Darrow at the last minute. The telegraph read:

DISTINGUISHED COLLEAGUES OF YOURS HAVE SUGGESTED YOU MIGHT BE WILLING TO COME TO TESTIFY FOR DEFENSE AT DAYTON TENNESSEE NEXT WEEK IN THE CASEOF STATE OF TENNESSEE VERSUS PROFESSOR SCOPES STOP WE OF THE DEFENSE WOULD BE DELIGHTED TO ADD YOUR AUTHORITY TO OUR POSITION STOP YOUR EXPENSES WILL BE PAID STOP WILL YOU WIRE ME DIRECTLY AT DAYTON AND I WILL LET YOU KNOW WHAT DAY YOU WILL BE NEEDED

According to Lafollette, Davis also drafted testimony for the expert witnesses once the trial was underway. He and Frank Thone, a writer at Science Service, even gave up their rooms at the hotel in town to stay with the defense witnesses at the private residence they had rented—dubbed the “Defense Mansion.” Photographs of the reporters, scientists and defense team gathered on the steps of the residence reveal their congenial bond.

The epitome of the “embedded” journalists, Davis and Thone stood openly in support of the science of evolution, and they saw it as their duty to help interpret the technical scientific language of the experts into something comprehensible for the general public. For their coverage of the trial, the editor of the New York Times sent a letter of thanks to Science Service.

Despite their valiant efforts, Davis and Thone’s contribution was unable to turn the debate. In the end, Scopes, who never even testified during his own trial, was convicted and fined $100. Soon after, other states, such as Mississippi and Arkansas, passed their own anti-evolution laws. Textbook publishers, wary of having their product banned, removed all reference to the subject for the next 30 or 40 years.

It wasn’t until 1968 that the U.S. Supreme Court banned anti-evolution laws—although that didn’t guarantee evolution was taught. In anti-evolution states, the old laws were quickly replaced with new laws mandating equal time for the teaching of creationism. The topic continues to fuel legal battles over science education today.

Meanwhile, the name Scopes has become an invective for just about any divisive issue that pits religious beliefs against science in education. For his part, Scopes gave up teaching when the trial was over, left Dayton to get a master’s degree from the University of Chicago and took a job as a petroleum engineer in Venezuela where his notoriety would not follow him.

The town of Dayton returned to the sleepy state it was in before the trial but remained the butt of national jokes for many years. It was even memorialized as the seat of fundamentalist bigotry in the 1955 play and subsequent movie Inherit the Wind staring Spencer Tracy and Gene Kelly. In rebuttal, the community eventually began hosting an annual Scopes trial play and festival that emphasizes the publicity stunt and paints a more favorable portrait of Dayton circa 1925. The festival continues to this day.

Surely none of that could have been predicted 90 years ago when a group of small-town businessmen from Tennessee answered an ad in a Chattanooga newspaper.