Sean Scully’s Artworks Are a Study in Color, Horizon and Life’s Sorrows

With a return to the Hirshhorn following his 1995 retrospective, Scully presents his sublime Landlines series

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/7b/cb7b1379-1edc-48b0-8f06-b011100bc9a4/land_sea_sky_photo.jpg)

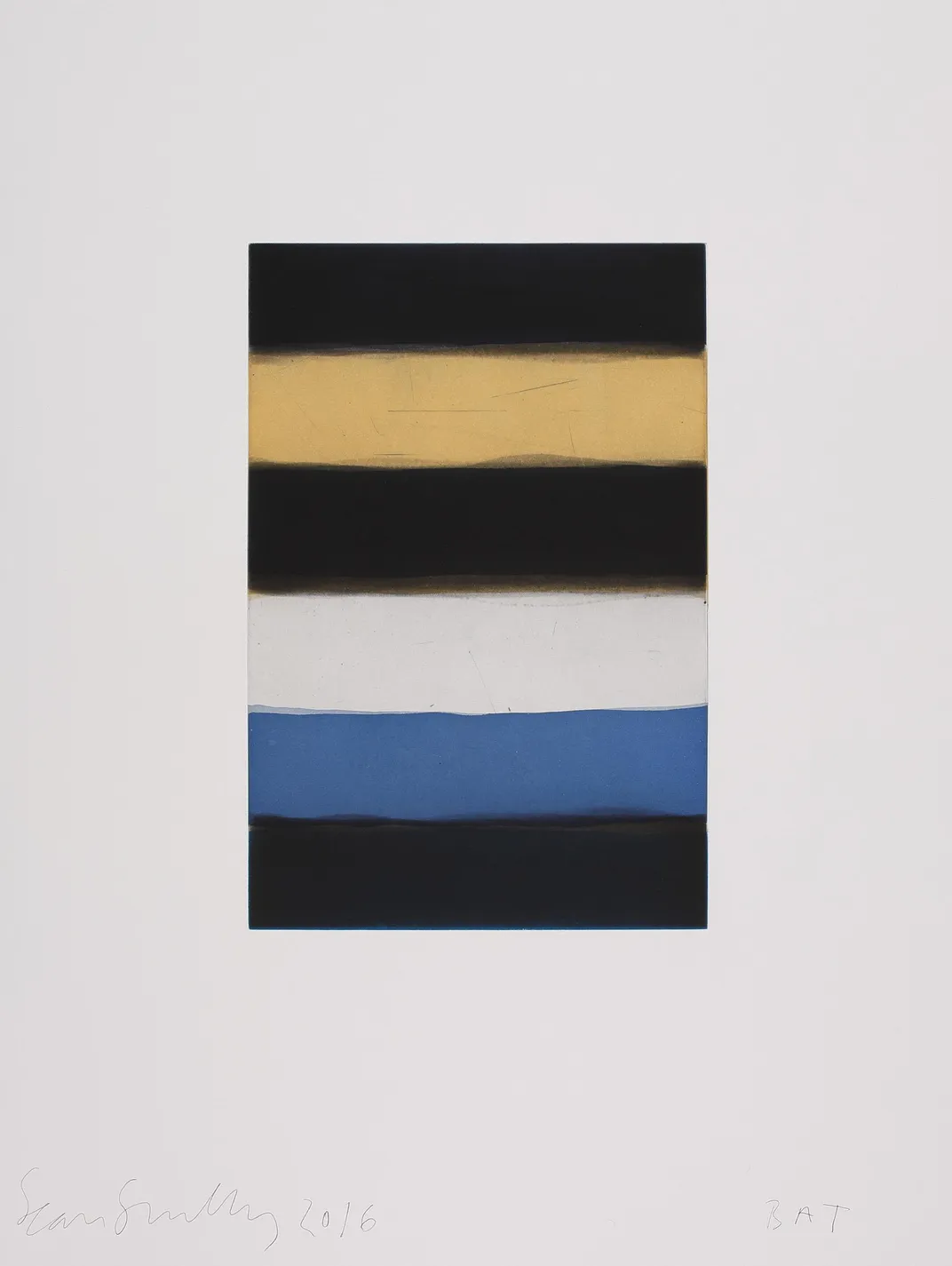

It was 1999 when the artist Sean Scully approached the edge of a grassy cliff in Norfolk, England, out to the blue-green of the North Sea and the steely gray sky above it. “I saw a beautiful cliff and a very unusual possibility for a composition,” he says. The resulting photograph Land Sea Sky presented those three elements in roughly equal stripes across the pictorial space.

The composition would inspire what would become his Landline series, which just opened at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. It features nearly 40 paintings that use horizontal stripes in thick gestural brushstrokes that at once bring to mind the color fields of Mark Rothko, a more organic approach to the stripes of Gene Davis, and the natural horizons that inspired it in the first place.

“I’m really in the business of unifying these two tendencies that have been at odds in our human history for a very long time: the logical and the romantic,” he told Hirshhorn director Melissa Chiu in an artist’s talk the night before the show’s September 13 opening.

More to the point, he hopes to “rescue abstraction from the abstract,” as he told Patricia Hickson, contemporary art curator at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, where the show will travel in February, 2019.

In the accompanying catalog, published by Smithsonian Books, Scully compares looking at the sea to an experience at Ireland’s Aran Islands in Galway Bay, gazing across the cold Atlantic. “I try to paint this, this sense of the elemental coming together of land and sea, sky and land, of blocks coming together side by side, stacked in horizon lines endlessly beginning and ending,” he says, “the way the blocks of the world hug each other and brush up against each other, their weight, their air, their color, and the soft uncertain space between them.”

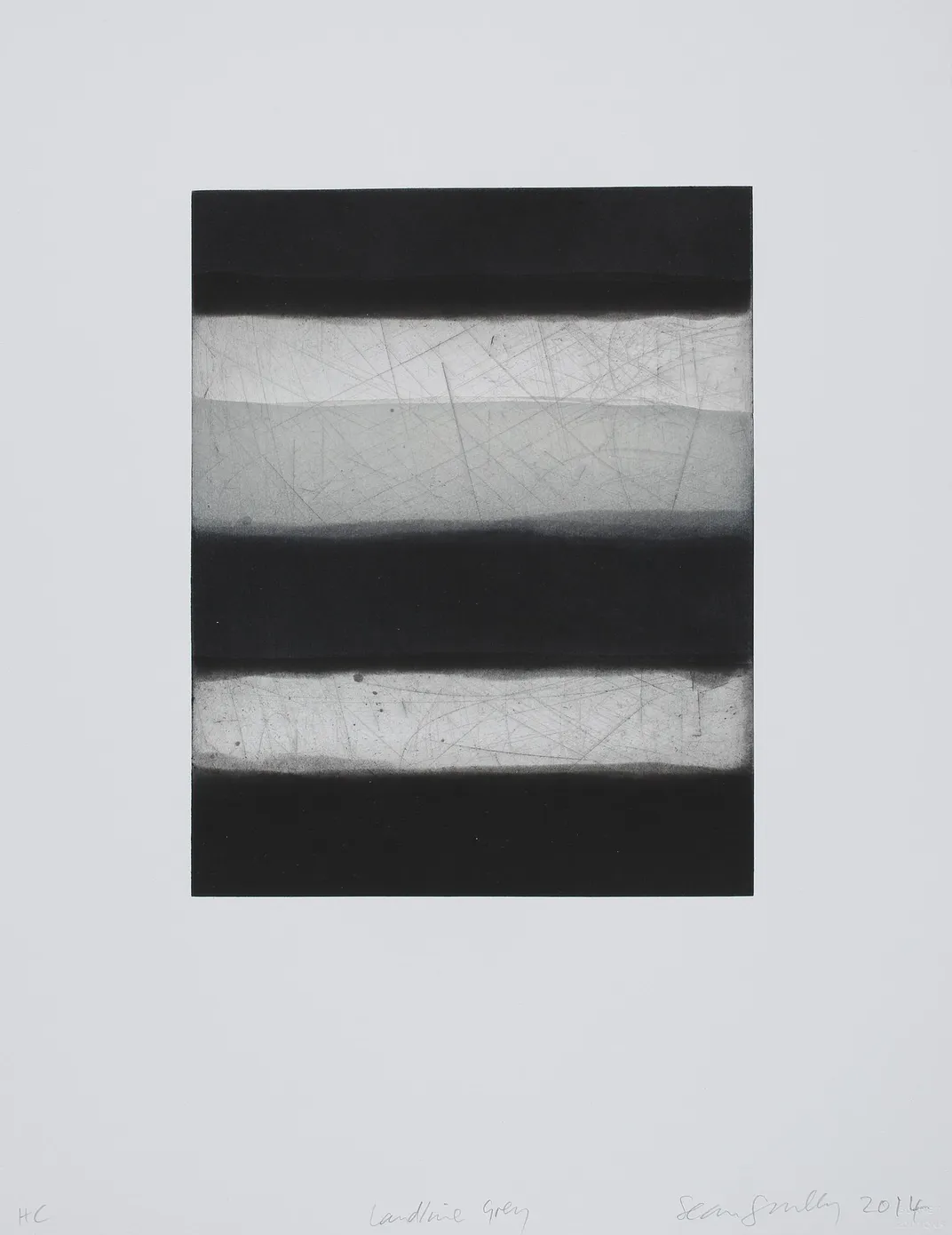

The resulting paintings, nearly two dozen of which had never previously been on view, line the walls on the Hirshhorn’s second level inner-circle galleries—some in watercolor, some pastels on paper, others in aquatint, and quite a few oils, on linen as well as aluminum and copper. The number of stripes increase from three to threefold that, but the dynamic approach in overlapping color and interest in the edges where they meet are constant. There are also three sculptures of boxes piled high and painted in shiny automotive paint of similar tones that reflect the same notions of stacked blocks of color.

Born in Ireland, Scully, 73, studied art in England before emigrating to the United States in 1975. He received his first mid-career retrospective at the Hirshhorn in 1995. He’s one of the first Western artists to have had a career-length retrospective exhibition in China in 2014.

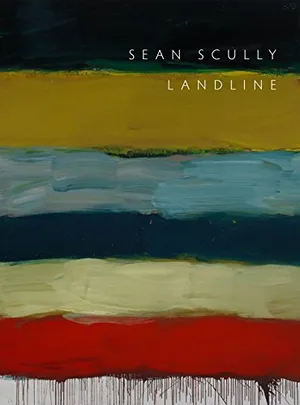

Sean Scully: Landline

Known for combining the geometry of European concrete art with the ethereality of American abstraction, Sean Scully is recognized as a leading artist of his generation, and his signature aesthetic overlays thick, gestural brushstrokes on grids of stripes and squares to evoke the energy and beauty of the natural world.

It was his solo exhibition at the 58th Venice Biennale Land Sea in 2015 that led to the current show. It’s one of two Scully exhibitions opening this month. "Sean Scully: Inside Outside," his first museum exhibition of sculpture and painting in the UK, opens September 29 at the Yorkshire Sculpture park.

“As abstract as they look,” Hirshhorn chief curator Stéphane Aquin says of the Landline paintings, they “actually open up the door to figuration in his work. They are landscapes, and they sit on the edge of abstraction and figuration.”

“Sean Scully continues to be one of the most influential painters working today,” Chiu says.

“My job is to return abstraction to the people,” Scully said in his D.C. artist’s talk. “In a sense to popularize it without lowering the bar, which is a lot easier said than done.”

Some of the lines and colors of his Landline series reflect melancholy. He painted them in his Chelsea studio after suffering the loss of his son and after being waylaid by an Oxycontin addiction following a back injury.

“Painting is profoundly emotional,” he says. “When I finish a painting, I’m usually extremely sad.” That’s reflected in some of the color choices of deep blues, blacks, ochres and greens.

In a written message dated August 16, 2015, that is part of the exhibit, Scully knew he was on to something with his first Landline. “I painted it on a quiet Sunday in Chelsea. There was an immense sadness in and around me. In the plants, the living things, the material of the studio. My life has been story of great sorrow and great love. Landlines stand for edges.”

After a career creating brighter and more geometric woven patterns, Scully found that painting horizontal stripes, with his injury, was both easier and more harmonious. He borrowed the hues of his thickly applied paint—some of it glossy from its application to copper—from classic European paintings from Courbet, Veronese and Titian. “I’ve looked at them adoringly for so many hours, and I’ve absorbed all their lessons,” he says.

Under-layers of gray give them an emotional undertow. “I probably use more grays than any other artist in the history of art,” he says.

His variations on the approach come in inserting contrasting windows of color in the middle, or, in some of his most recent work, a few canvases of squiggling lines that suggest the plowed rows of rich farmland.

Through it all, Scully is surprised that his very personal paintings emanating from that shoreline photograph, found a wider audience at all.

Finishing one of his first Landline paintings, Scully says, “I felt that nobody would buy it, and I decided I could just be on my own for a couple of years and make these paintings that I wanted to make.”

“But people bought them faster than the ones I made before,” he adds. “So you never know what’s going to happen.”

“Sean Scully: Landline,”curated by Stéphane Aquin with assistance from Sandy Guttman, continues at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden through Feb. 6, 2019.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)