Birds, for the most part, do not live in nests. These complex structures, sometimes meticulously assembled for more than a month, tend to be used for the express purposes of incubating eggs and raising young. But despite their common goal, birds’ nests are widely variable, ranging from woven baskets to hammocks made from saliva to a spot of mud on the ground, just sparsely lined with grass.

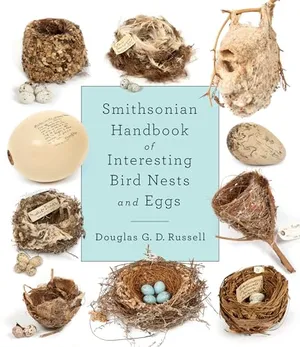

The Smithsonian Handbook of Interesting Bird Nests and Eggs, set to release on September 17, highlights some of the most fascinating avian constructions housed in the collection of the Natural History Museum in the United Kingdom.

Douglas G.D. Russell, a senior curator responsible for the bird nests and eggs at the Natural History Museum’s location in Tring, Hertfordshire, wrote the book based on the specimens he looks after. The museum’s collection of eggs and nests represents more bird species than any other collection of its kind on the planet. It hosts about 5,000 nests and roughly 300,000 clutches of eggs, with the oldest dating to 1768. The museum has the only verified nest of a greater bird of paradise in a scientific collection—and it sits outside Russell’s office.

“Nests are extraordinary remnants of behavior,” Russell says. “And the fact that these incredibly, in many respects, robust and beautiful little bits of architecture exist, I think, is such a testament to millions of years of evolution.”

A preserved bird’s nest is also a time capsule, providing scientists a window into a past era. The plant material or animal remains included in the construction can give clues to what species lived in the area at the time, or perhaps the past climate. When birds build a nest using human-made trash, it offers a record of our species’ influence on the environment.

Even just holding on to the structure and conserving it in a museum collection could enable new discoveries in the future. When Russell began his work with the collection 23 years ago, he was told that unless the plant material in a nest included something identifiable—like a seed head or a flower—there was no way to discern its species. But now, scientists can extract DNA from the specimens and determine their components.

Smithsonian Handbook of Interesting Bird Nests and Eggs

Bird lovers can admire the artistry and beauty of bird nests and eggs with strikingly sharp images of more than 100 specimens.

Using modern technology and potential future innovations, researchers could soon make more discoveries from preserved nests. “They’re yet to have their finest hour,” Russell says. Beyond plants, “we haven’t even started to look at major other components of nests, like arthropod silk, arthropods sitting in there. What else is sitting in those nests, and what does that tell us about the ecology at the time? What does it tell us about the behavior that constructed those nests? That’s what’s really amazing.”

Still, the breeding ecology of only about 30 percent of the world’s bird species is deeply understood by scientists, Russell writes in the book. In tropical regions, researchers have rarely or never recorded the breeding behavior of up to 80 percent of birds. This leaves huge gaps in knowledge about lots of potentially at-risk species. And birds, Russell says, are at their most vulnerable when breeding.

Nests and nesting birds are also hard to observe. “It’s one thing to find the bird. It’s entirely another to find its nest,” Russell says.

The Natural History Museum’s collection is so vast in part because of Britain’s colonial history. British naturalists traveled all over the world during the roughly 400 years of the British Empire and brought home natural specimens for study.

When crafting the book, Russell didn’t necessarily choose the flashiest bird nests and eggs in the collection. He wanted to represent a wide range of species and families of birds, depict a variety of breeding ecologies, and include a nod to the distinct histories the nests and eggs represent.

Here are just a few of those stories, tracing conservation successes, incredible avian behavior, scientific advances and the looming threat of extinction.

Cape penduline tit

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c4/04/c4044adb-17c0-4822-8a23-6644278527c9/cape_penduline_tit.jpg)

Cape penduline tits are among the smallest birds in Africa at just three inches long, but they nevertheless manage to create an ingenious nest with built-in protections from predators.

For more than 20 days, the male and female birds work together to construct their nest—a pear-shaped bundle of plant material and spiderwebs from velvet spiders. By including this sturdy spider silk, the birds make their nests exceptionally durable; Russell points out that the museum collection’s sample of this nest is still strong more than a century after it was collected.

As a security measure, the nest has a self-closing tube at the entry hole that the bird has to open with its foot. When this “door” shuts after the adult bird enters or leaves the nest, it inconspicuously conceals the eggs and nestlings inside. But if that’s not enough, the tit has another trick to thwart snakes and other would-be predators: The nest includes a false entrance beneath the real one, leading to an empty, decoy chamber.

This particular nest was found at the top of a tall tree in Angola, some 20 feet above the ground. The bird species is called “penduline” as a reference to the hanging nature of its nest, like a pendulum.

Liben lark

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ff/8c/ff8c18d1-97be-4a1c-80d6-8a837e836a3b/liben_lark_copy.jpg)

Though the Liben lark is classified as a critically endangered bird, so few are left that Russell says it might already be gone—or if it isn’t, it seems to be headed that way. “That is something which we are almost certainly going to lose,” Russell says. If the Liben lark does disappear, it will become the first recorded bird to go extinct on mainland Africa.

Liben larks are residents of the Liben Plain, a small, 13-square-mile stretch of flat land in southern Ethiopia. With human development, encroachment of woody plants and conversion to agriculture, the plain’s native grasses are dwindling and these birds with them.

When this example of a Liben lark nest was first discovered in 2018, it hosted three nestlings, but since it was empty just days later, researchers assumed it had been found by a predator. It represents the Liben lark’s struggle to stay alive. Being native to Ethiopia, the Liben lark also is less likely to receive conservation funding from Western initiatives, which often focus on birds in North America and Europe, Russell adds.

“I think more people should think about and talk about extinction every day, because therein lies the lesson,” Russell says. “Every single one of these is something that we have lost with a story of how we lost it.”

House sparrow

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/53/97/5397fa45-acc1-42b1-8c5e-7e9cc4e71a1f/house_sparrow.jpg)

House sparrows are considered the most widespread birds around the globe, though they’re native to most of Europe, as well as parts of Asia and northern Africa. Suburban residents might even recognize the house sparrow’s nest, perhaps having seen it under their roof eaves. These hardy birds can thrive in human-made environments, and this nest is a case in point: It was collected from the exhaust pipe of a helicopter in wartime. “I couldn’t think of any other example which would more succinctly illustrate their flexibility,” Russell says.

Found at the beginning of the Iraq War in 2003, this nest demonstrates female house sparrows’ preference for nesting in holes. It came from the exhaust pipe of a British Royal Air Force helicopter in the Middle East. It’s constructed from desert grasses native to the region where the British Army’s Joint Helicopter Command was based, along with fig-marigold, goosefoot and artificial items such as plastic.

Buff-spotted woodpecker

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f9/9c/f99c9d1a-f51e-4bb9-bc51-890e1496d664/buff-spotted_woodpecker.jpg)

Woodpeckers are known for nesting in the cavities of trees, boring holes by drumming on the trunk with their specialized beaks. But the buff-spotted woodpeckers that used this creation found a different place to lay eggs: a nest of arboreal termites.

When woodpeckers use a termite nest like this one, the insects are still there—the nest is “alive,” so to speak. That’s because the birds rely on the termites to maintain the structure and keep it intact. After this nest was found in the early 1900s in Cameroon, scientists later spotted other bird species using termite nests to raise their young, including kingfishers, parrots and trogons.

Village weaver

The village weaver nest is a particularly special one to Russell—along with biologist Jackie Childers, he researched this individual nest for two years. They had rediscovered it in the museum’s collection, but the specimen presented only mysteries.

“It had one little old label, which was registered in 1866, and it just said, ‘Niger Expedition,’” Russell says. “But we knew nothing. We didn’t know for certain which species built it. We didn’t know for certain where it was collected or when it was collected.”

To an extent, they had an idea of what it was. Weavers are known for their complex nest construction, intertwining plant fibers together in a feat of avian engineering. This nest seemed to belong to a village weaver, a black-and-yellow bird native to sub-Saharan Africa, but the researchers wanted to find data to back up the idea.

Ultimately, through historical research and comparative analysis, they uncovered that the village weaver nest had been collected by botanist Julius R.T. Vogel on July 26, 1841, in Ghana, shortly before Vogel’s death. It was collected on the Niger Expedition, which is also called the African Colonization Expedition, a British mission to spread Christianity, make treaties with native people and promote trade.

This “difficult” colonial past puts the nest “at the intersection between natural history and history,” Russell says. The nest is an “extraordinary survivor from West Africa, and the fact that we can rebuild its history, I think, is extraordinary.”

White-nest swiftlet

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/48/80/4880ee91-2c81-49d7-8e7f-64a032ea5d06/white_nest_swiftlet.jpg)

Residents of Southeast Asian islands and coasts, white-nest swiftlets frequently gather over water in large flocks. But because they look so similar to other small, brown swifts, the birds are best identified when sitting in their signature white nests—edible creations that are coveted and harvested by humans across much of the species’ range.

The male white-nest swiftlet (also called the edible-nest swiftlet) creates the pale nest by secreting saliva from a pair of glands under his tongue. The birds often nest in caves, where colonies of them will dot the walls with their hammock-like nests, which take around 39 to 55 days to make.

Bird’s nest soup, created by boiling the nest, is one of the most expensive soups in the world and is considered a delicacy in China, where it has been used for medicinal purposes for centuries. The mild soup has been compared to egg whites in both texture and flavor.

Trade in the swiftlet’s edible nests is long-established in Asia. This nest was collected in the mid-1800s through British and Dutch trading posts in the region. Today, many nests used in soups are farmed rather than collected from the wild.

White-winged chough

The white-winged chough is a nearly all-black bird, except for its characteristic red eyes and white patches on its wings, which are seen in flight. It’s one of two remaining birds in Australia known as the mudnesters, and it constructs its nests on horizontal branches of trees, such as eucalyptus.

This specific nest was likely created by a group of up to 18 choughs. The species lives in large flocks, in which young birds remain with their parents for years and will help build the nest. The painstaking construction process is long: White-winged choughs pile mud in layers, with each layer given time to dry before the next is added on top. Often, this endeavor takes several days—but if the area hasn’t seen much rain, the birds might not be able to find mud, and the process could extend to months.

Found in the late 1800s in southeastern Australia, this nest measures about seven inches across. Historically, some white-winged chough nests have been more than 13 inches in diameter.

Echo parakeet

At first glance, the echo parakeet’s nest doesn’t look like anything special. It might even appear like “a really boring picture,” Russell says. “It’s a plastic thing with some unidentifiable bits of woodchip and egg.” But this nest is one of his favorites. “You’d be hard pressed to find a more poignant example of how the studying of the nesting and breeding of a species can bring something back from the absolute brink of extinction.”

When this nest was discovered in 1987, the echo parakeet was the rarest and most endangered bird on the Mascarene Islands of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. Only a handful of the vibrant green birds remained. Conservationists led an effort to find the last nest sites of the species and study how it reproduces, then used that information to design a captive breeding program that dramatically bolstered the birds’ numbers.

Now, hundreds of echo parakeets fly through the canopy of Mauritius, and their population is increasing. Their conservation status improved from critically endangered to endangered in 2007, and in 2019, it was changed again to the less dire ranking of vulnerable.

“In terms of conservation, you cannot save a bird if you don’t understand … when, where and how it breeds,” Russell says. The story of the echo parakeet is a strong testimony to why it’s important to learn from birds’ breeding behaviors, eggs and nests. “That is so key to our global efforts in bird conservation, and that’s why this information matters.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1521x1362:1522x1363)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ec/3c/ec3cf3c7-94ac-495a-8c68-d3061171e420/eggsandnests_-20211210-248-bokmakierie.jpg)