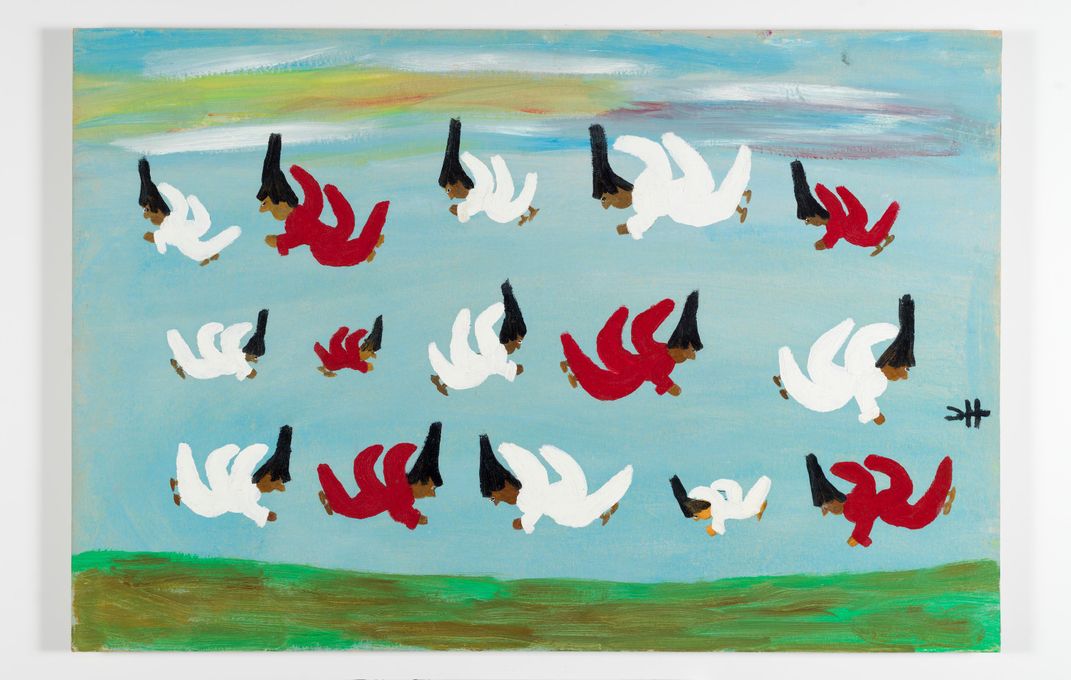

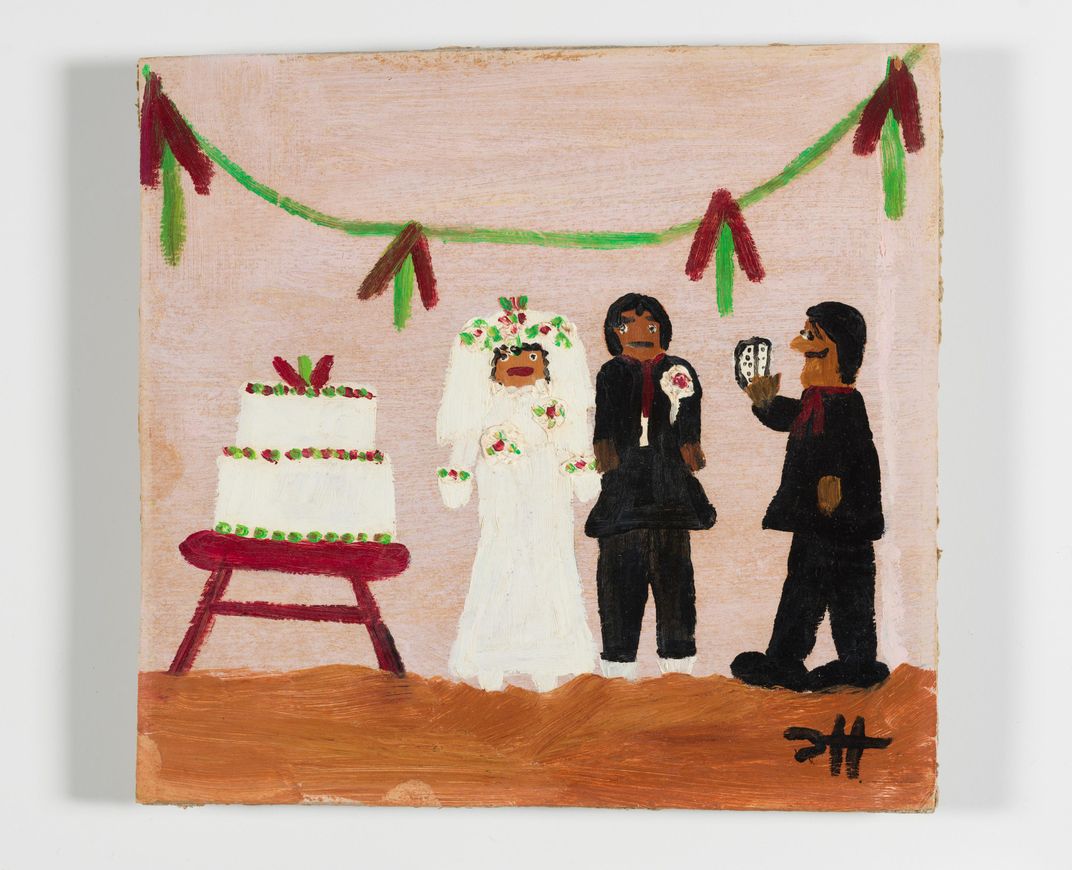

Self-Taught Artist Clementine Hunter Painted the Bold Hues of Southern Life

On view at NMAAHC, Hunter’s colorful artworks depict work in the field, church on Sundays, and laundry on the line

She was born just 20 years after the Civil War. Her grandparents were enslaved. And after decades of working in a storied Louisiana plantation, Clementine Hunter picked up a brush and began depicting African-American life in the South, turning out thousands of paintings first sold for less than a dollar that are now fetching thousands.

Often called the black Grandma Moses, for the simplicity of her work and her late life enthusiasm for it, the artist, who died in 1988 at age 101, is being celebrated in an exhibition held in the Rhimes Family Foundation Visual Art Gallery at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

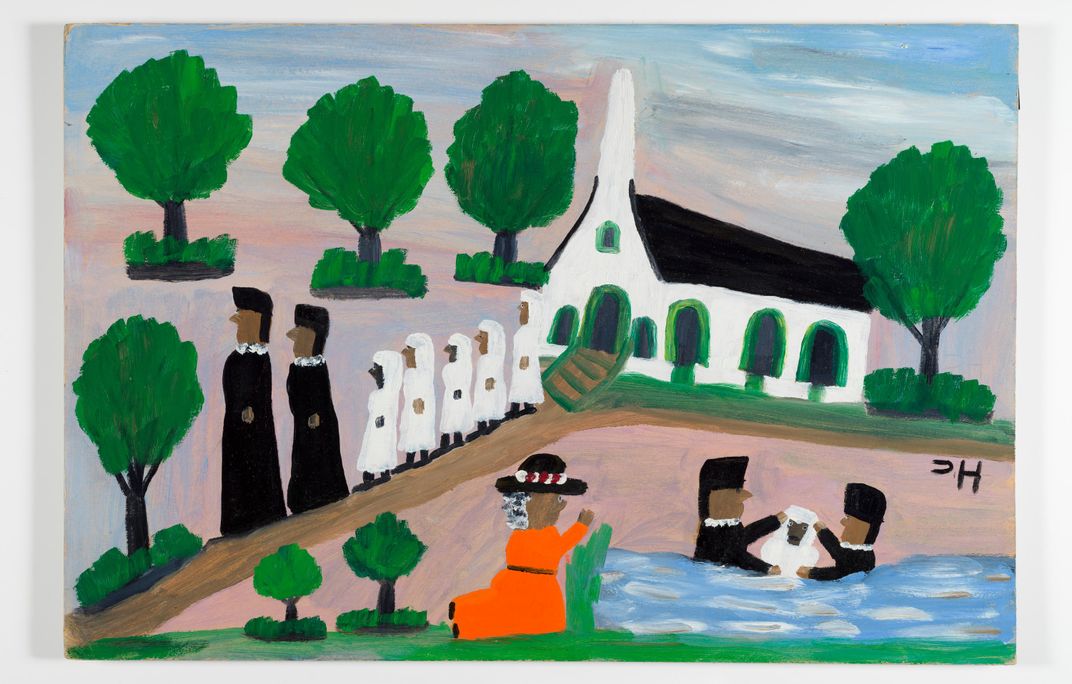

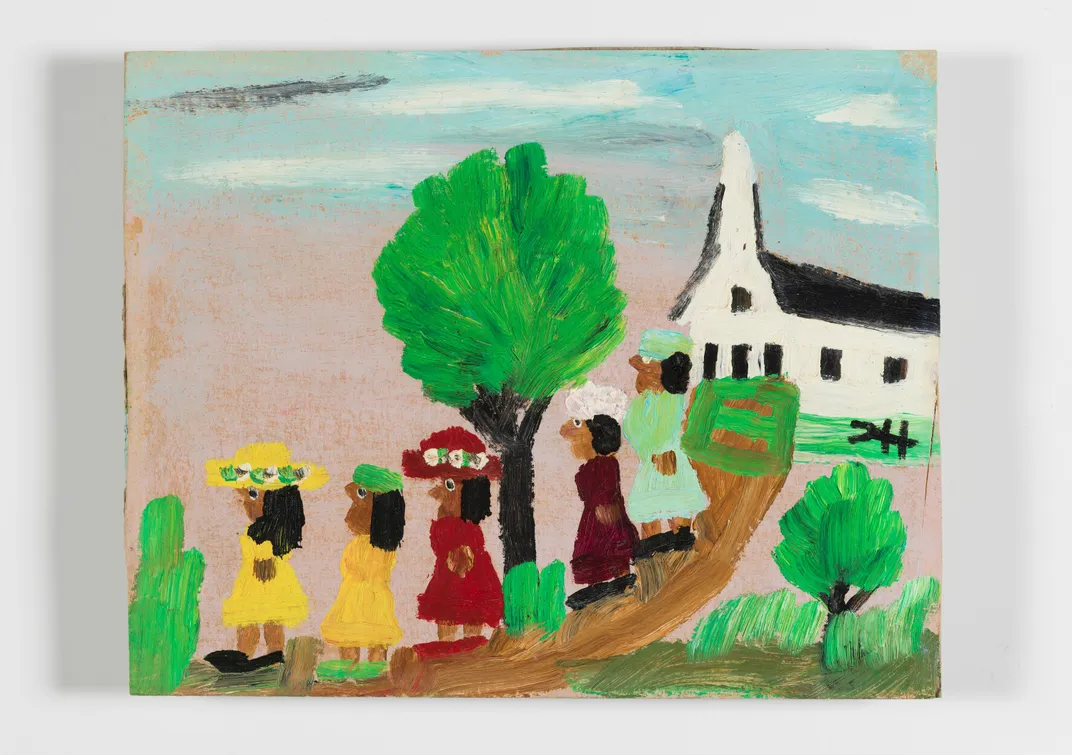

The 13 works in “Clementine Hunter: Life on Melrose Plantation,” drawn from 22 in the museum’s collections gifted to the museum by three different donors, are divided into themes that recurred in her art: religion, daily life and the plantation landscape (Another Hunter painting, Black Jesus, hangs in the museum’s permanent art collection).

“This is the largest collection of art we have by a single artist,” says Tuliza Fleming, the museum’s curator of American art. “We really wanted to do this show to highlight a woman artist and also a self-taught artist.”

Hunter was born into a Creole family at the Hidden Hill Plantation, thought to be the inspiration of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. It was there, in the Cane River region of central Louisiana where she began working in the fields while young, receiving less than a year of formal education and never learning to read or to write.

Her family moved to Melrose Plantation, south of Natchitoches, when she was 15, continuing to work picking cotton and harvesting pecans until the 1920s when she became a domestic worker, cooking and doing laundry.

“Melrose Plantation was interesting because it was started by a mixed-race Creole,” Fleming says. By the time Hunter moved there, it was run by a woman who cultivated the arts, and “would have artists from all over the country come and live as artists in residence.”

The writers and artists who spent time there in the out buildings she restored and brought in, ranged from William Faulkner and writer Lyle Saxon, to film star Margaret Sullavan, critic Alexander Woollcott and photographer Richard Avedon.

When New Orleans artist Alberta Kinsey left some brushes and discarded tubes of paint after a visit in 1939, Hunter began to dabble with them, making pictures first on window shades, then on any kind of suitable material.

She painted so much that François Mignon, the plantation curator, brought them to a local drugstore to sell for a dollar. Hunter also illustrated Mignon’s 1956 Melrose Plantation Cookbook. And, supplied with materials by Mignon, her paintings were available for viewing in the shack where she worked for 25 or 50 cents.

“He was the one who really promoted her art,” Fleming says of Mignon. “He saw her talent and he encouraged that. He would buy her art supplies.” Mignon also got her to install a series of murals that stand today on the plantation’s so-called Africa House, so named because it was thought to have Congolese origins to its design (when actually it traced to the French).

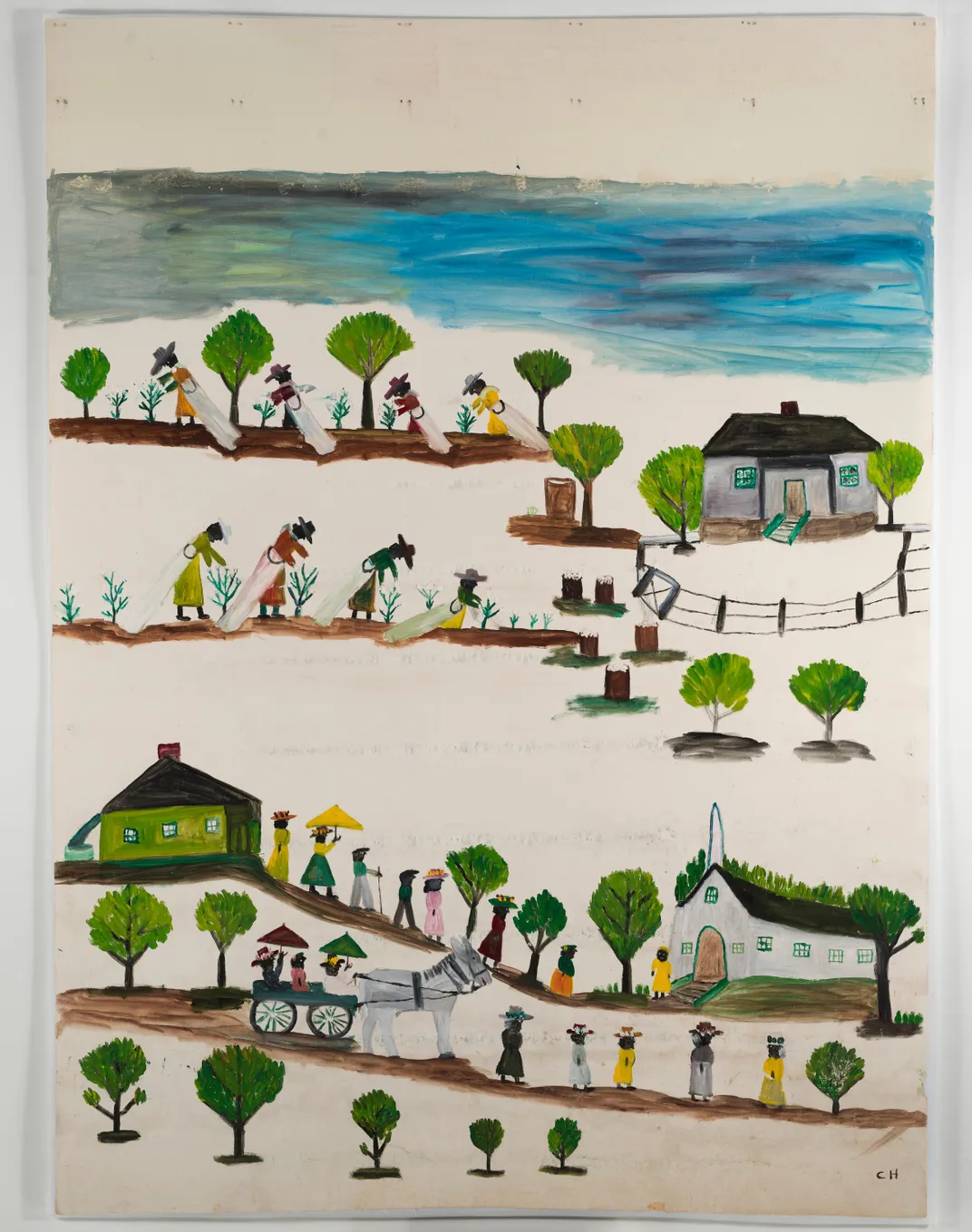

The works on display show life on the plantation, with work in the field, laundresses busy hanging sheets in the Louisiana sun and everyone pausing to go to church on Sundays.

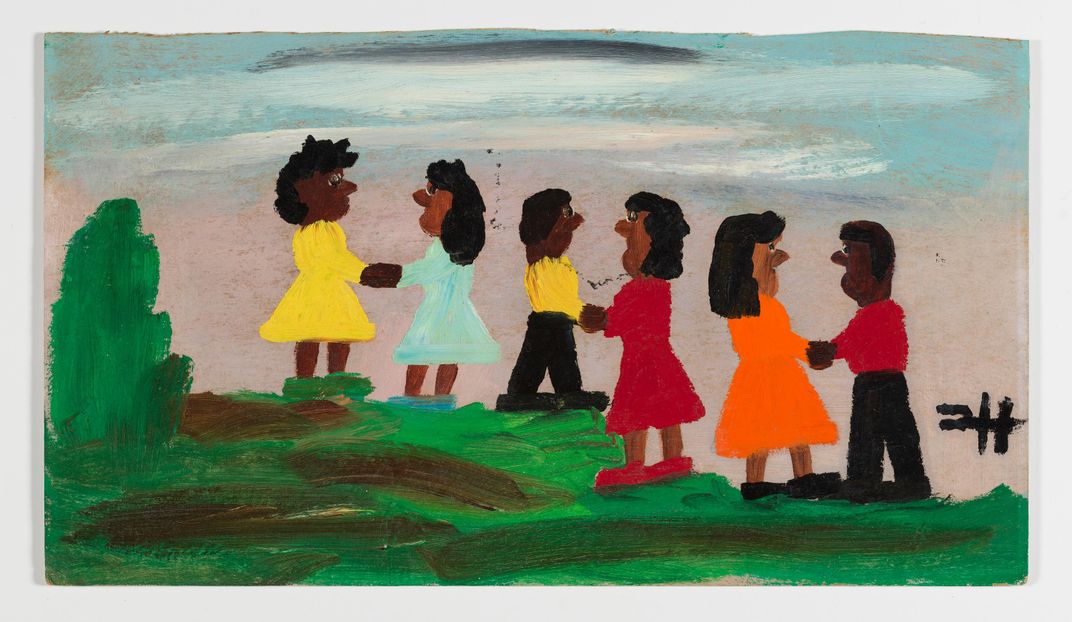

She depicted life in bright colors and simple shapes, but she also imposed her own vision as well.

“One of the things you’ll see throughout her work is that the men tended to be smaller than the women,” Fleming points out. “She always elevated women’s work and women within her paintings. And I don’t know exactly why she made the men smaller, but people say she had a lower opinion of them.”

Hunter’s sheer productivity can be attributed to her long life. “She lived to 101 and painted every day until toward the end of her life. They say she painted between 5,000 and 10,000 paintings,” Fleming says. “It was something she felt compelled to do. There are certain artists who can’t stop creating and she was one of those artists.”

Painting on the variety of materials she used, from cardboard to Masonite to wood, presented a special challenge to conservators, says Jia-Sun Tsang, senior conservator at the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute. None more than a painting done on a window shade that was nonetheless still used as a shade, such that years of rolling and unrolling put marks in the piece. The work had to be flattened and retouched, but when it was hung in a new frame, the original window roller was restored as well.

“It’s very unusual material,” Tsang said of the window shade as canvas. “I’ve never worked with it before.”

The exhibition at the popular, two-year-old National Museum of African American History and Culture is not the first museum show for Hunter, whose works hang in many museums. During her lifetime, she was the first African-American artist to have a solo exhibition at what is now the New Orleans Museum of Art. But because of Jim Crow laws of the era she couldn’t attend.

When Jimmy Carter invited her to the White House during his presidency, Hunter declined—because she didn’t like to travel outside of Louisiana.

“Clementine Hunter: Life on Melrose Plantation’ continues through December 19, 2019 at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)