Seventy-Five Years Ago, Women’s Baseball Players Took the Field

An Indiana slugger was one of the athletes who “hit the dirt in the skirt” and changed Americans’ view of women

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/a2/dea25e4e-a299-432e-b3fc-eb0618ead377/jun2018_b01_prologue.jpg)

Betsy Jochum’s 1940s baseball tunic was tailor-made for the American woman’s transition from the decorative to the active. With a short, flared, kicky hem disguising the athletic undershorts that were the real purpose of the rig, it was designed for a ballplayer who had to look like a girl but throw like a guy, who wore her hair in an upsweep but “hit the dirt in the skirt,” as Jochum and her teammates liked to say of sliding into home plate.

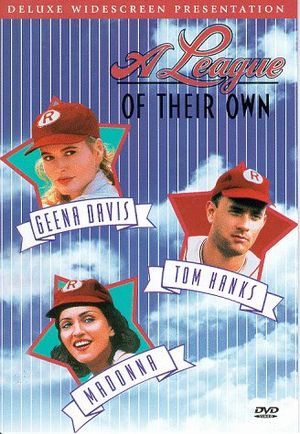

Any number of powerful consorts, witches, reformers and suffragists populate the history of women in the United States, but it took a handful of ballplayers to give them real muscle. The All-American Girls Professional Baseball League—founded 75 years ago, on May 30, during the manpower shortage of World War II by Chicago Cubs owner Philip Wrigley—allowed women like Jochum a brief, 11-year window in which to radically extend the acceptable range of female behavior. A 5-foot-7 office girl with a quick bat, a long stride and a radiant smile, “Sockum” Jochum became the star slugger for the South Bend Blue Sox and hit .296 to win the 1944 batting crown in the now-legendary league. But then it all stopped. The league disbanded, the demure 1950s took hold, and Jochum was a forgotten Indiana schoolteacher until the story of the Rockford Peaches, Racine Belles and all the rest was memorialized by director Penny Marshall in the popular 1992 film A League of Their Own.

A League of Their Own

Hired to coach in the All-American Girls Baseball League of 1943, while the male pros are at war, Dugan finds himself drawn back into the game by the heart and heroics of his all-girl team.

“Without the movie, nobody would have ever heard about us,” says Jochum, now 97 and a resident of South Bend, whose uniform resides in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. “Nobody would’ve ever known.”

The uniforms, partly conceived by Wrigley’s wife, were modeled on figure skating and tennis dresses to give players a feminine appeal yet allow them to move. Players were put through a Helena Rubinstein-run charm school in which the 22-year-old Jochum learned to glide down stairs gracefully. The league’s player-conduct manual, “A Guide for All American Girls: How to Look Better, Feel Better, Be More Popular,” mandated chaperoned dating, no smoking in public and no slacks. “The smart looking teams invariably play smart ball,” it pronounced.

Their schedule was an unladylike grind of 115 games from May to September. They were on the field seven nights a week with double-headers every Sunday and holiday, sometimes on diamonds that had gravel-strewn base paths that left their legs looking less than dainty. They’d play until 9 or 10 p.m. and ride a bus all night to the next town. But their contracts paid $50 to $85 a week, and fans pitched in bonuses, such as an RCA radio for Jochum. It seemed like a fortune compared with the $16 a week she made operating a key-punch adding machine called a comptometer at a Cincinnati dairy in the off-season. “When you get paid to play, there’s no better feeling than that,” Jochum says.

The ballplayers were for the most part factory-town women happy to have the paycheck until the men got home, observes Kelly Candaele, a filmmaker whose PBS documentary about his ball-playing mother was the inspiration for Marshall’s film. “Most of them didn’t approach this thing academically, like, oh, they were pioneers and proto-feminists,” he says. It was decades before they grasped how much they meant to the workplace, how much credibility they conferred on their gender with sheer physical competency, similar to the more than 475,000 Rosie the Riveters who worked in the U.S. munitions industry. If Jochum’s uniform is emblematic of what a little opportunity can do, it’s also threaded with stigma and represents the halting one-step-forward, two-steps-back progress that women faced. When Jochum asked for a raise, her disapproving club owner traded her to Peoria. “If you didn’t do what they told you, you know how that goes,” she says. Instead of accepting the trade she retired in 1948, got her college degree at Illinois State and became a middle school physical education teacher in the South Bend schools.

Still, the demonstration of muscle by Jochum and her fellow ballplayers meant that no male entitlement would ever be safe again. A 2015 Ernst & Young survey of high-level female executives found that 90 percent of them played a sport; among women holding a C-suite position, the proportion rose to 94 percent. It’s a testament to the enduring power of the women in A League of Their Own that Amazon is developing a new TV series based on them. “We proved that women can play,” Jochum says.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.