In the bright sunshine high above the Korean peninsula, the silver-skin of 39 B-29 Superfortresses gleamed as they flew in formation. Their mission that day on April 12, 1951, was to destroy a bridge on the Chinese border and disrupt the flow of munitions and men pouring into North Korea.

Lumbering along at just more than 300 miles per hour, the heavy bombers were the pride of the United States Air Force. Viewed as “invincible,” the piston-engine aircraft had helped win World War II against Japan six years earlier by dropping tens of thousands of tons of bombs on the island nation, as well as two atomic weapons.

For this attack, the Superfortresses were escorted by nearly 50 F-84 Thunderjets, a first-generation jet fighter. The much-faster straight-wing planes had to throttle back considerably to stay with the bombers.

Suddenly from high altitude, the Americans were swarmed by lightning-fast enemy jets. Featuring a swept-wing design and powerful engines, approximately 30 MiG-15s swooped down and began peppering the American bombers and jets with cannon fire. Adorned with North Korean and Chinese markings, these aircraft were actually flown by top Soviet pilots who had honed their skills against some of the best German aces during World War II.

The slow B-29s were easy pickings for the superior MiG-15s. The Soviets darted in and out of the formations, shooting down three Superfortresses and heavily damaging another seven bombers. Outmaneuvered and outclassed, the American escort jets were helpless against the attack. In the confusion, they even shot at their own planes.

“Our MiGs opened fire against ‘Flying Superfortresses,’” Soviet ace Sergey Kramarenko later recalled. “One of them lost a wing, the plane was falling into parts. Three or four aircraft caught fire.”

It was a humiliating defeat for the U.S. Air Force. While most military leaders knew the days of piston-driven bombers were numbered, they didn’t expect it would be that day 70 years ago, which became known as Black Thursday. American bombing missions over the Sinuiju area in North Korea were grounded for three months until enough squadrons of F-86 Sabres, a swept-wing jet that matched up well against the MiG-15, could take on this new challenge in the Korean War.

The air battle over “MiG Alley,” as this sector of North Korea was called by Allied pilots, changed the course of the conflict between the world’s superpowers.

“By 1951, the B-29 Superfortress was an antique, though we didn’t know it at the time,” says Alex Spencer, curator in the aeronautics department at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. “Things went very badly, very quickly for the bomber forces. This battle changed the nature of the American air campaign over Korea.”

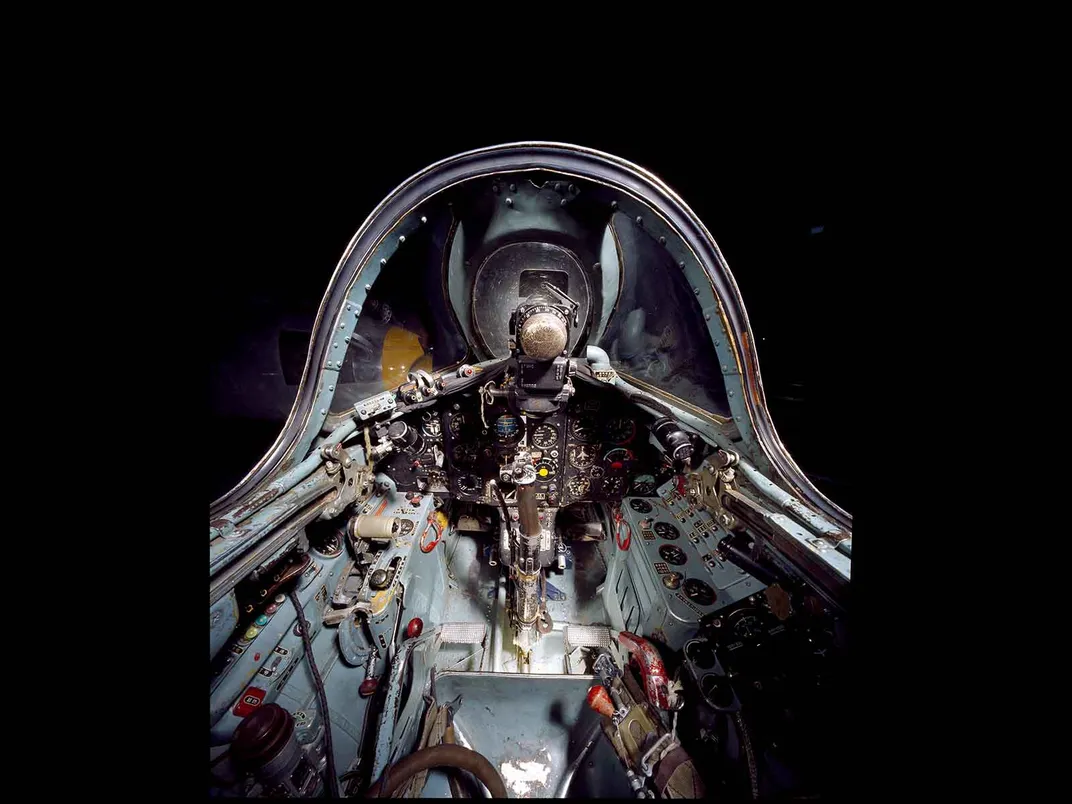

The MiG-15 shocked the West with its capabilities. This aircraft looked eerily similar to the Sabre but had certain improvements—namely its ceiling level. The MiG-15 could fly at heights of 50,000 feet, giving it a slight upper hand over the F-86. Plus, the Soviet jet carried cannons, not guns: two 23-millimeters, plus a 37-millimeter. The Sabre was equipped with six .50-caliber machineguns.

Those armaments had a destructive effect on the B-29 Superfortresses, says Mike Hankins, the museum’s curator of Air Force history.

“The kill rate of bombers by MiG-15 was devastating,” he says. “The larger cannon was made to take out B-29s. You get a few of those cannon hits and the whole thing could go down. I heard some pilots referring to them as ‘flaming golf balls.’”

Those heavy weapons, plus the high-altitude capability, made the MiG-15 a formidable aircraft. The Air and Space Museum displays one of these jets in the Boeing Aviation Hangar of its Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia. The MiG-15 is positioned near its archrival, the F-86.

“The MiG-15 could drop and do these hit-and-run attacks,” Hankins says. “They would go into a steep dive, follow a path and hit as many bombers as they could. If they shot them down, that was great. If they damaged them enough to keep them from getting a bomb on target, that was also great. The aircraft was very effective at that.”

Developed by Soviet aircraft designers Artem Mikoyan and Mikhail Gurevich, the MiG-15 stunned American military leaders when it first appeared over Korea in 1950. It was far superior to the Shooting Stars and Thunderjets, and quickly chased them from the sky.

This is what happened on Black Thursday. The F-84 jet fighters with their straight-wing design similar to World War II aircraft were at a definite disadvantage to the streamlined MiG-15.

“Our early fighter jets were not very good performance-wise,” Spencer says. “The designers at that time were still working on what they knew. With the F-86 Sabre, you get the introduction of the swept wing, which made a huge difference in the performance of jet aircraft.”

But before the Sabre’s arrived on the scene, the American fighters could not keep up with the much faster MiG-15. Sorties of three and four enemy jets zoomed down on the helpless Superfortress bombers, then quickly zipped back high out of range from the American fighters.

“The F-84s were much slower,” Hankins says. “And they were also going slower to stay with the bombers. The MiGs were so much faster, the American pilots just didn’t have a chance to catch up. It caught them by surprise.”

For Soviet pilot Kramarenko, it was an important moment. Not only did his squadron prevent the bombing of the Yalu River bridge, it demonstrated to the world that the Soviet technology was on a par with the American's.

“I still remember the image in my mind: an armada of planes is flying in combat formation, beautiful, like during a parade,” Kramarenko told a journalist years later. “Suddenly we swoop down on top of them. I open fire on one of the bombers—immediately white smoke starts billowing out. I had damaged the fuel tank.”

After Black Thursday, the U.S. Air Force called a halt to its long-range strategic bombing campaign and waited three months until it could get enough F-86 Sabres into the air over Korea to match the Soviets. Only then were B-29s allowed to resume missions to MiG Alley along the Chinese border–and only when accompanied by Sabres.

“For several months, the battle affected B-29 operations,” Hankins says. “It put limits on what the Air Force was willing to do and where they were willing to send the bombers.”

While considered by many experts as the equal of the Sabre, Spencer believes the Soviet jet might have had a slight advantage. It was a durable aircraft and easier to maintain, he notes.

“The MiG-15 was a very robust aircraft,” Spencer says. “That was a characteristic that Soviet designers kept going throughout the Cold War. Their aircraft were able to operate in much harsher conditions and much rougher airfields than our aircraft were able to do.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/79/357932a4-4618-4590-92bf-1ec0e71795e8/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f0/73/f0732487-7643-4df6-8144-5026204e1b09/plane3.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)