The Short Rise and Fall of the Crazy-for-Cocoa-Trade Cards Craze

In the late 19th-century, when you bought chocolate, the grocer dropped a delightful prize into your bag, a trade card to save and share

In the archival collections of the American History Museum, a handful of richly illustrated advertising trade cards, dating from the 1870s to the 1890s, offer a slice of the history of chocolate. Together, they tell a tale of the industry, artistry, ingenuity and even villainy of chocolate from its Mesoamerican origins, its journey to Europe, and its arrival in the industrialized United States.

In 1828, the ingenious Dutch chocolatier Conraad Van Houten rendered obsolete the highly complex artisan craft of grinding small amounts of cacao on a stone with his mechanized hydraulic presses. A burgeoning middle class stood ready to purchase the less expensive finely powdered cocoa. The 1820s also saw the arrival of a new method for printing using colorful inks, giving advertising a bright new face. The craze for collecting and sharing advertising trade cards saw its genesis at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia when exhibitors passed out the beautifully printed photo and illustrated cards pitching tools and machinery, patent medicines and other wares.

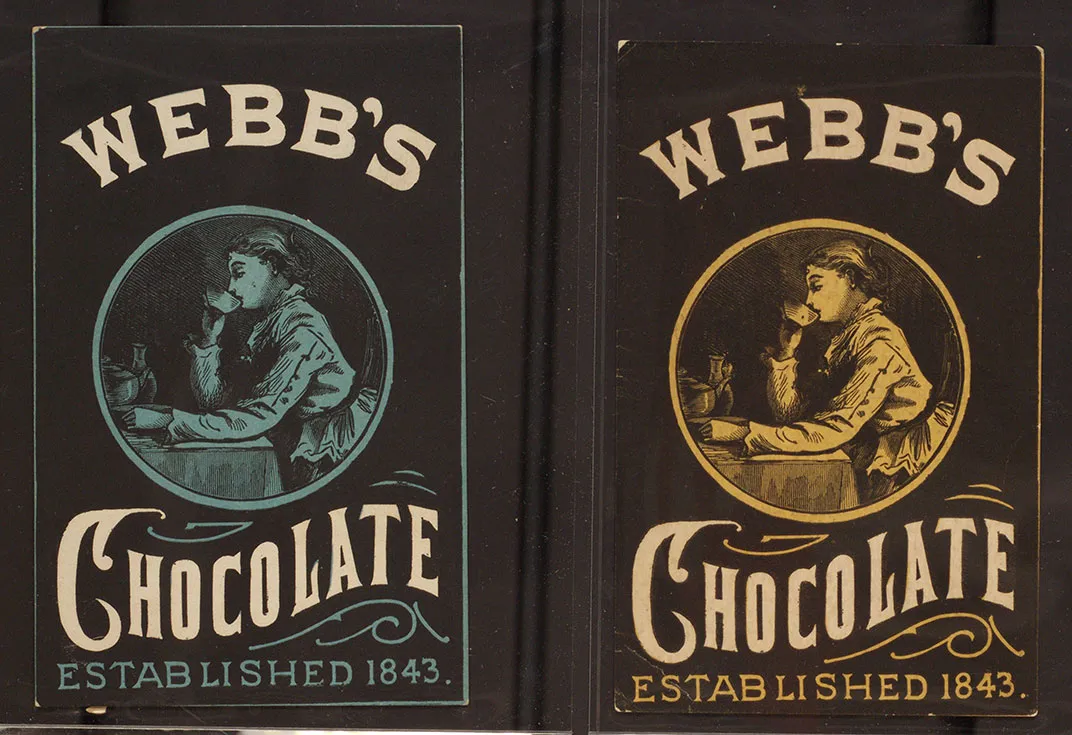

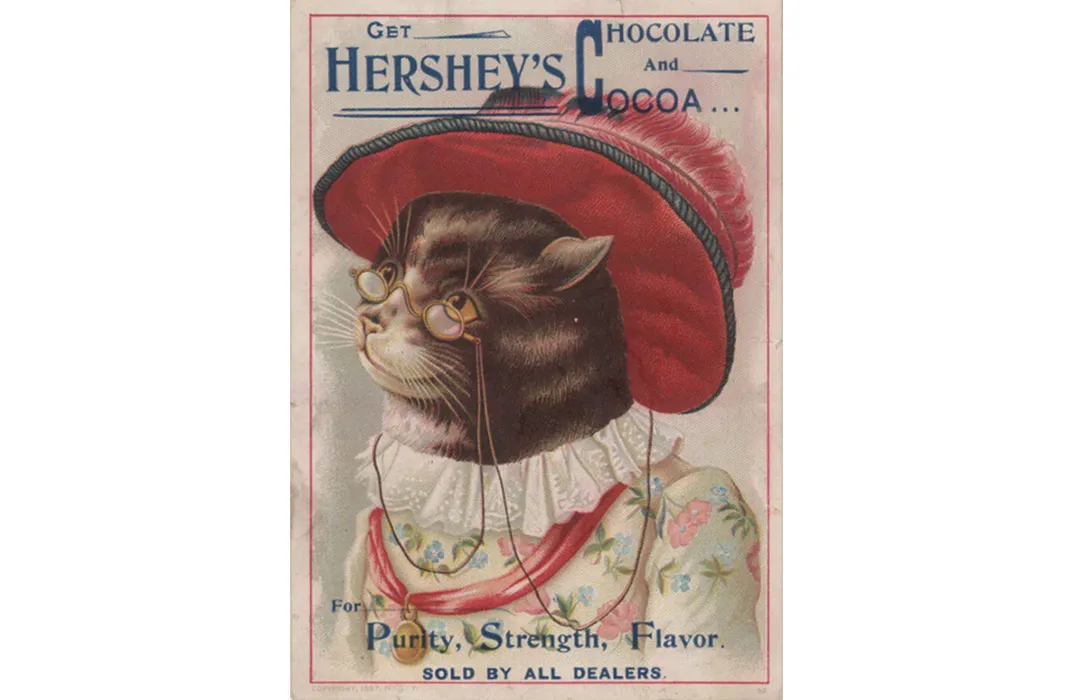

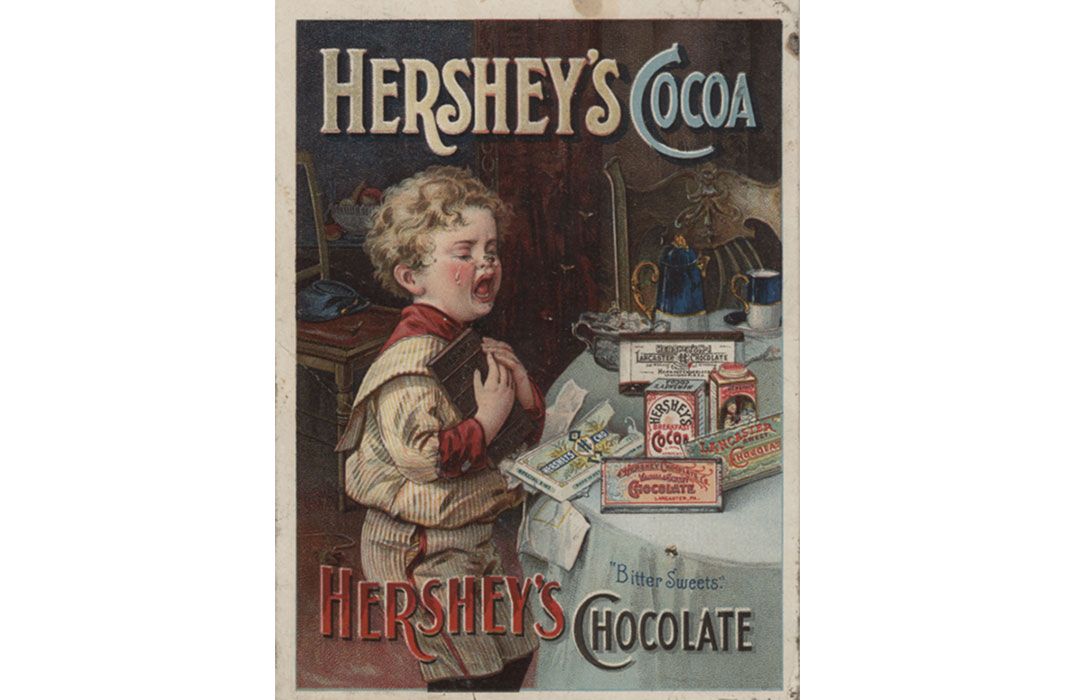

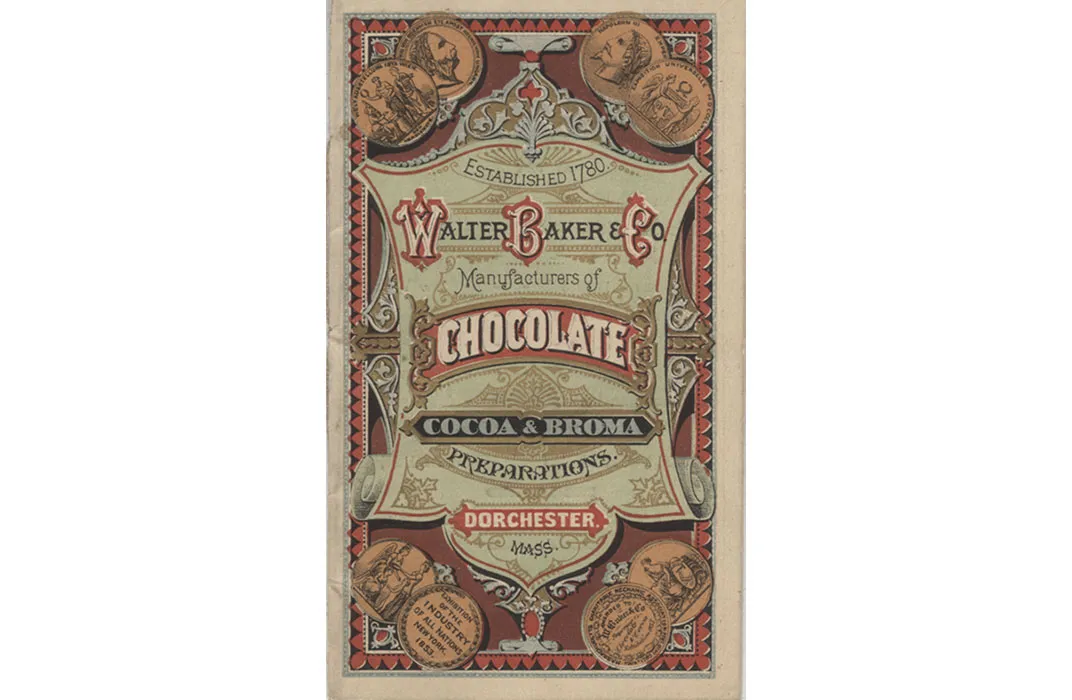

The world’s prominent chocolate makers of the period—Van Houten, Cadbury, Runkel, Huyler, Webb, Whitman and Hershey—embraced the trade card advertisements with a flourish. When you bought chocolate at the store, your grocer dropped a delightful prize in your bag—a trade card.

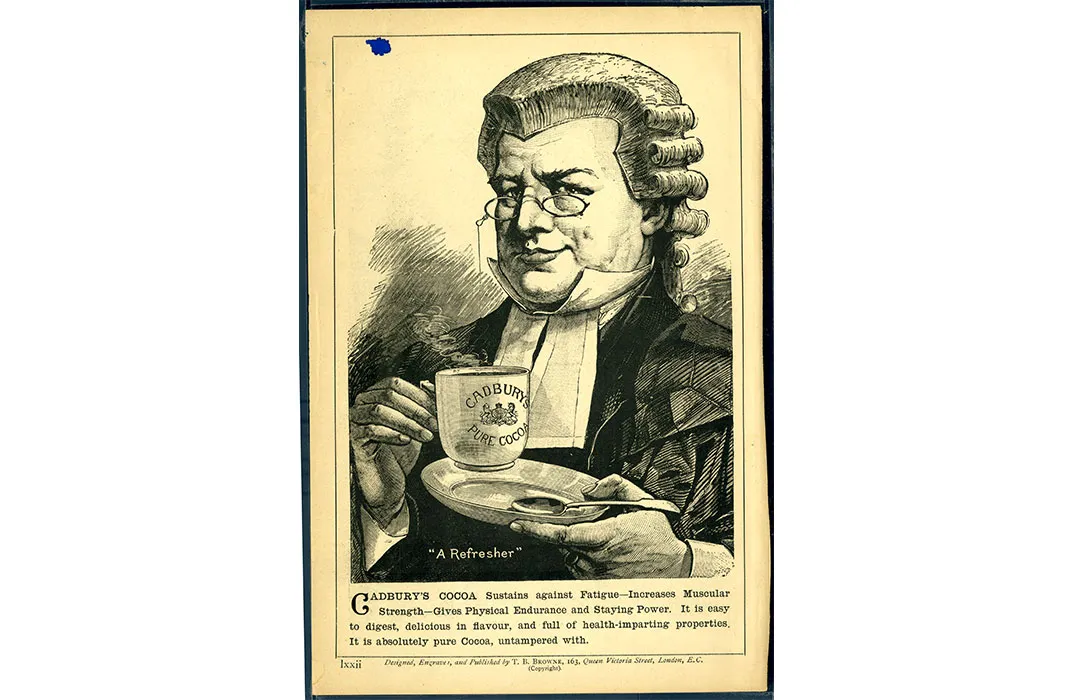

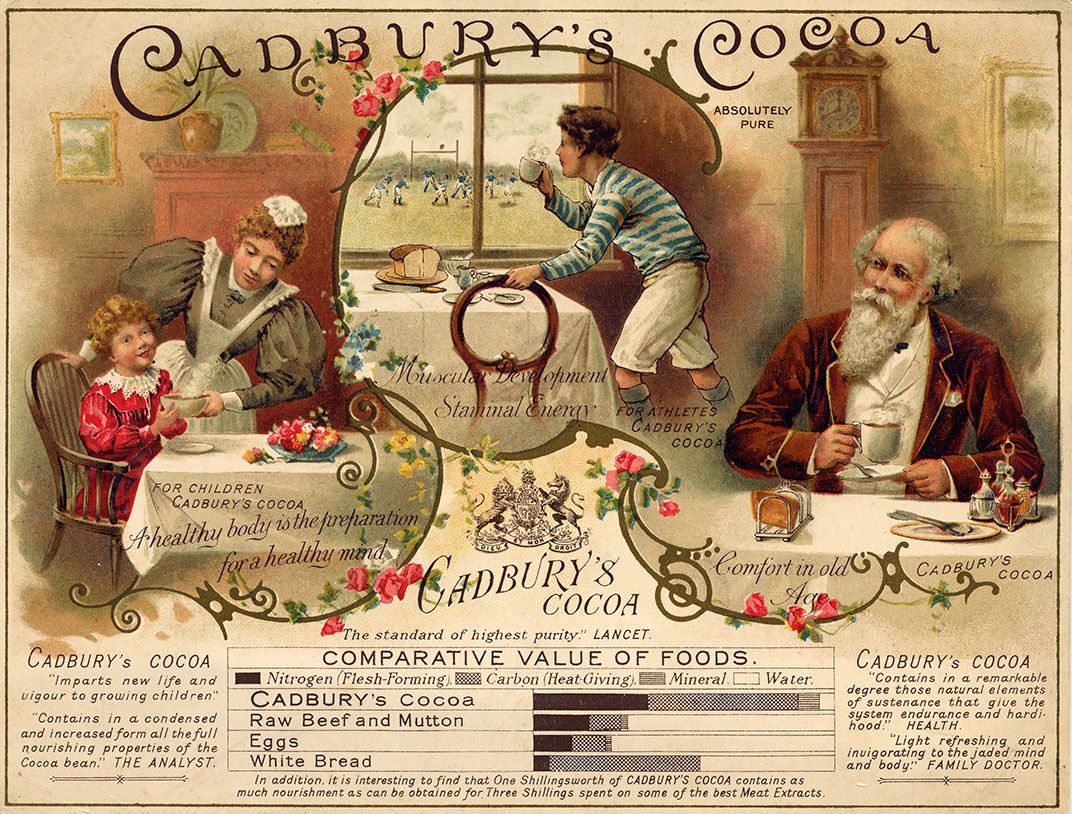

Some were designed with punch-out pinholes so that collectors could string them up in a window; others had folding instructions to create a three-dimensional displays. And from the cards, collectors were told of the product’s purity, its healthfulness and taught to prepare cocoa with recipes from the chefs of the day. Cocoa “imparted new life and vigour to growing children” in Britain, where red-cheeked and plump cherubic tots ate and drank chocolate for breakfast. While in Massachusetts, a chocolate maker called its product “a perfect food” and boasted of a Gold Medal won in Paris. Cocoa, said another, “sustains against fatigue” and “increases muscular strength.”

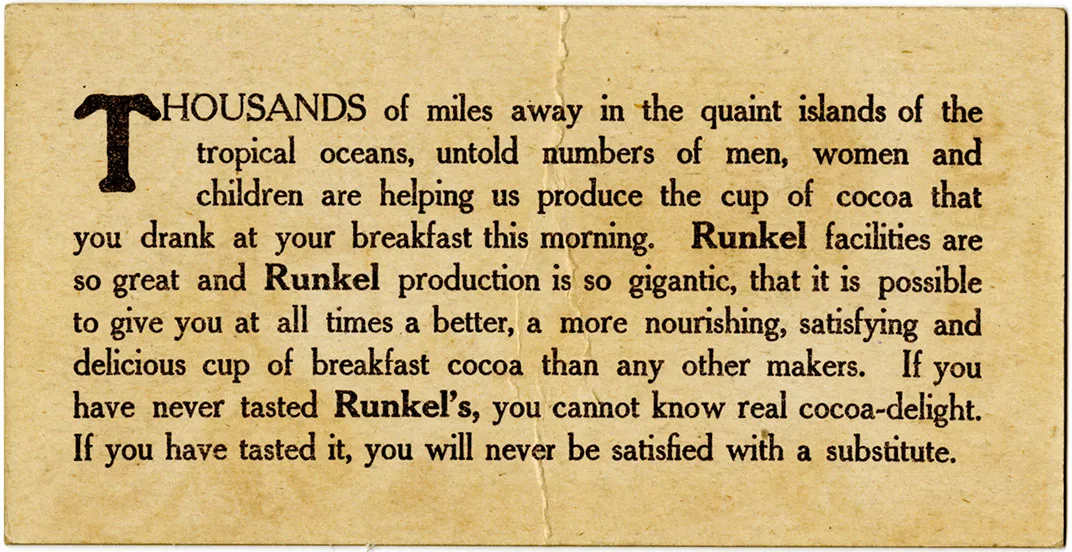

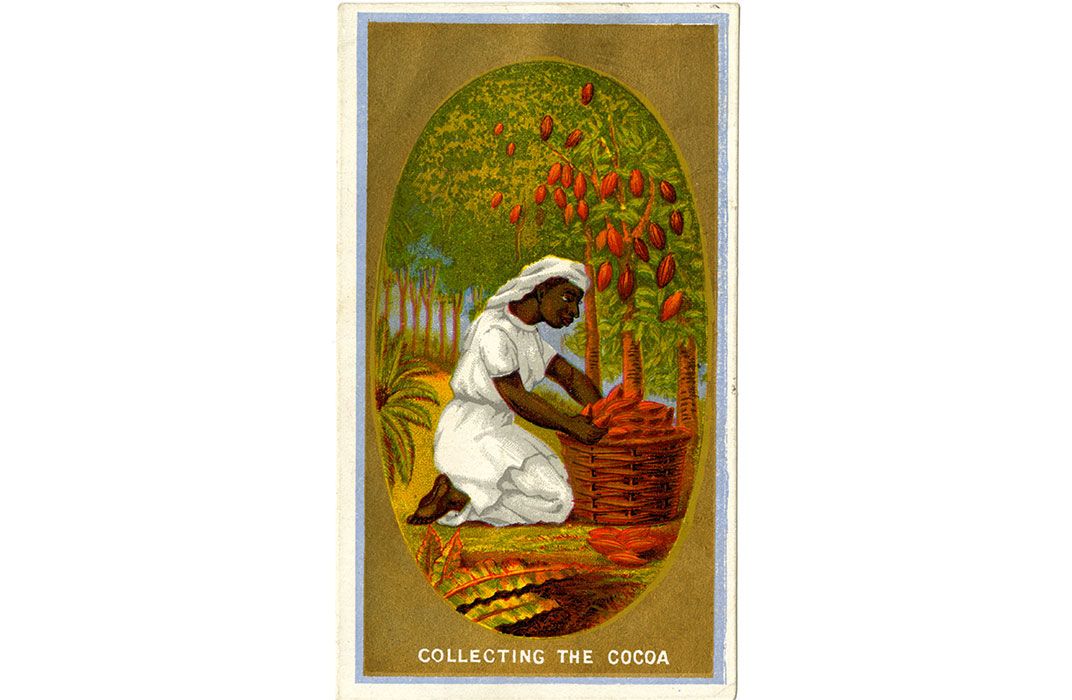

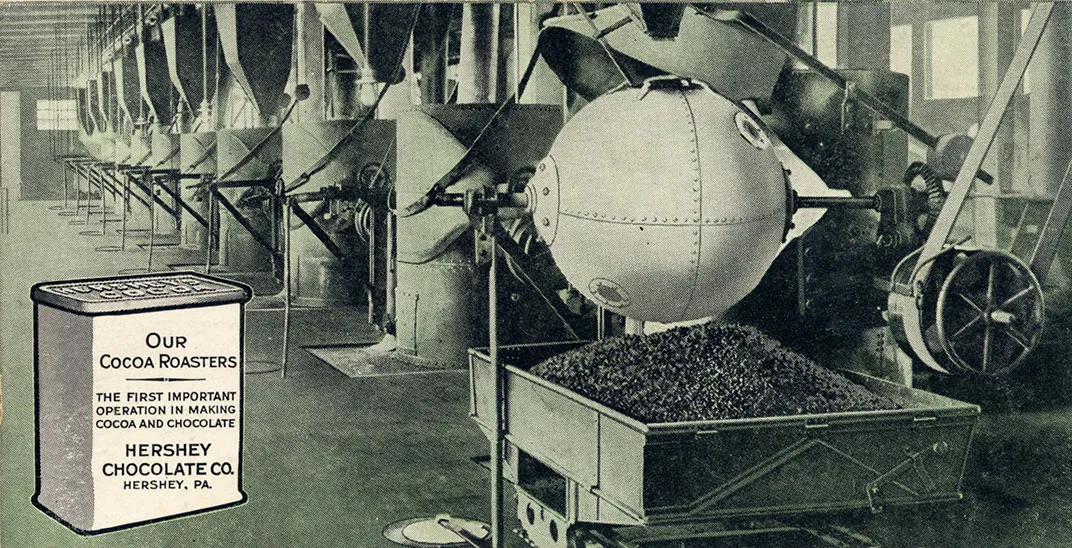

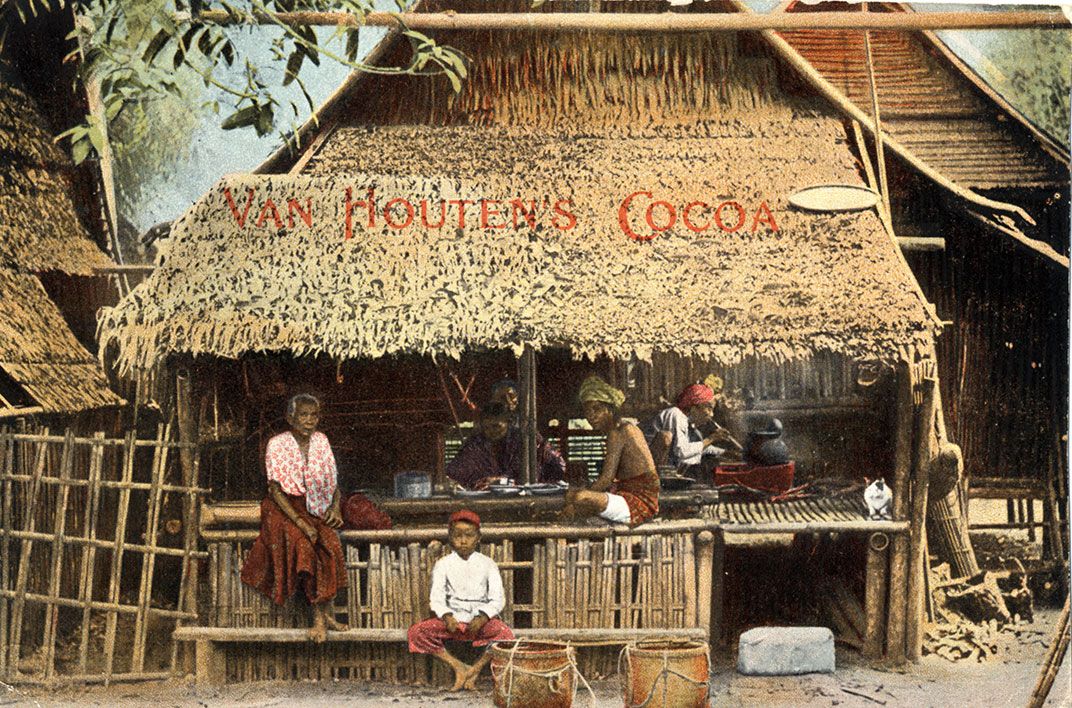

The cards depicticed romantic images of the chocolate business from field to manufacture. Native workers under thatched roofs or palm trees were idealized with storybook language—"thousands away in the quaint islands of the tropical oceans." An image of Hershey’s state-of-the-art Pennsylvania manufacturing plant depicted sanitized rows of efficient steam-operated roasters. And a Dutch girl served cocoa in a chocolate pot wearing traditional dress and wooden shoes.

Purity was of utmost concern to a public made suddenly wary of unscrupulous suppliers who had been caught adding crushed cacao shells, flour and potato starch, even ground red brick to cocoa products. Great Britain and eventually the United States stepped up with laws that prevented adulteration of food. Accordingly, Cadbury promised “the standard of highest purity” and that its cocoa was “endorsed by the most eminent physicians” to promote healthy bodies for the young and bring comfort to the old.

The advertising trade cards proved a short-lived fad. Cheaper postal rates made postcards a more efficient way to reach customers. For just a penny a pound, advertisers could now mail advertisements directly to people's homes, and by the turn of the century, low-cost, second-class postage made magazine advertising a far more effective way to reach an audience.

These trade cards, booklets and advertisements, above, are part of the Smithsonian Archives Center’s Warshaw Collection that collector and entrepreneur Sonny Warshaw and his wife Isabel amassed in their New York City apartment and in a nearby brownstone warehouse. The couple collected the invoices, advertising, photography, labels, ledgers, calendars and correspondence of largely American businesses, but some from around the world, simply because they believed that ephemera from these companies would one day provide a vital backstory. When the Warshaw Collection arrived at the Smithsonian in 1961, it had to be hauled in in two tractor trailers, but it has been providing that opportunity to historians and researchers ever since.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/e0/2be05edd-3559-42f0-a713-6ae0073d27c5/ac0060-0000690web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b5/68/b5681c27-9064-4042-8df0-72fd36e199ae/ac0060-0000605web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fe/8a/fe8aa7db-ec4d-4d47-8dd4-6a47ed08ba3b/ac0060-0000637web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/93/07/9307867e-bd81-4f49-a0a4-b56a5bef22fd/ac0060-0000636web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/26/4a26c555-eec0-49da-a526-d0c22aba6e3f/ac0060-0000631web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Beth_Head_Shot_High_Res-14-v2.png)