Should We Hate Poetry?

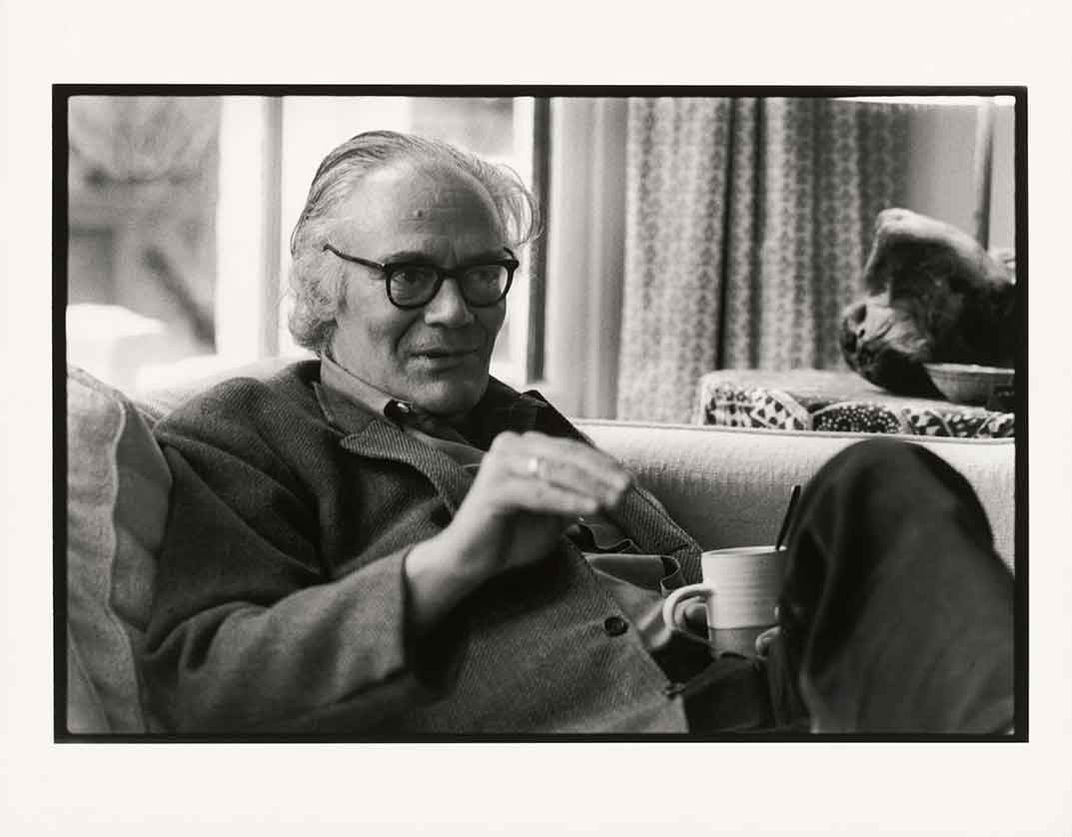

It was precisely because poetry wasn’t hated that Plato feared it, writes the Smithsonian’s senior historian David Ward, who loves poetry

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/50/cc/50cc7172-2b85-4b13-af30-0c36a3f3c83a/npg7964whitmanrweb.jpg)

Poet and novelist Ben Lerner’s little book The Hatred of Poetry, currently receiving some critical notice beyond the world of verse, is an entertaining cultural polemic that begins in certitude—Hatred—and concludes in confusion. Lerner’s confusion derives from the de-centered world of poetry itself, which is too capacious and slippery to be grasped unless the analyst is ruthlessly elitist, which Lerner, thankfully, is not.

The Hatred of Poetry is a wonderful title, guaranteed to draw attention and a marketing dream in the poetry community, but it misdiagnoses the condition of poetry. People do not hate poetry, although many are indifferent to it, or ignore it, or are frustrated by it. Lerner, whose novels include Leaving the Atocha Station and 10:04, is making a rhetorical claim with a conceit that he can’t support in his argument.

Very few of the other commentators Lerner cites share the philosopher’s hatred or meet the standard set by Lerner’s title. Indeed, Lerner rather undermines his own case, in the first comment that he cites on poetry, which is Marianne Moore’s “I, too, dislike it.”

Well, dislike is not hatred. Like most of us, Moore found a lot not to like about poetry, but she wanted it to be better—and she wanted an audience that was better placed to make judgments and distinctions about verse.

Rather, than hating it, I would argue that people love poetry too much. Because people want so much from poetry and because so many people have conflicting demands of poetry, the result is a continual sense of disappointment that poetry hasn’t lived up to our expectations. Like helicopter parents, we can’t just let poetry be. We always have to be poking and prodding it, setting schedules and agendas, taking its temperature and making sure it lives up to the great expectations we have for it. As with children, though, we seem fated to be continually worried about poetry—and always, at best, mildly disappointed at how it has turned out.

Lerner’s intention is an intervention or an annotation on the “state of poetry,” not a comprehensive or extended critical overview. It is an essay, more than a book, and is akin to the kind of pamphlet literature that dominated the public and political life well into the 19th century as printing became cheap and the culture was becoming democratized—Tom Paine’s political pamphlet Common Sense is an outstanding example.

The Hatred of Poetry’s charm comes from its glancing diffidence, a refusal of the hard-and-fast dictates that are the usual stock in trade of the cultural critic. More broadly, The Hatred of Poetry is part of the tradition of the jeremiad—a long list of woes about poetry that goes back to Plato and Socrates and which surfaces regularly in the Anglo-American literary world.

The staples of these jeremiads are twofold. First, the argument goes, most poetry simply isn’t any good. Most poets should stop writing and most journals and publishing houses should stop publishing. This is the high cultural, not to say elitist, critique of poetry: unless you’re Keats, you just shouldn’t write anything at all. Which rather begs the question of how you know you’re Keats until you have written and exposed your writing to public scrutiny.

This argument is a perennial, and is usually propounded by people with some degree of status as literary arbiters and who feel their place is under threat from the mob. It’s an argument that need not be taken too seriously simply because it isn’t going to happen. In popular political and cultural democracies, people can do what they damn well please, including writing poetry, despite what anyone tells them not to do.

Also, there is no Gresham’s Law of bad poetry driving out good; there were plenty of bad poets writing at the same time as Keats, their work just doesn’t survive.

The second argument, similar to the first but with a slightly different emphasis, is that poetry is too personal, that poets are concerned only with their own voice, and inadequately link their personal utterance with the wider condition of society and humankind; poetry is solipsistic, in other words, Or, in the words of W.H. Auden “it makes nothing happen,” existing only in the valley of its saying.

These contemporary criticisms are the opposite of the original, and still most powerful, attack on poetry, which was Plato’s.

For Plato, poetry made too much happen. It excited the imagination of the public leading citizens to indulge in fantasy and wish fulfillment not reality. Poetry was dangerous. It was precisely because poetry wasn’t hated that Plato feared it.

To return to Marianne Moore, she wanted us to be self-conscious readers not sycophantic ones who simply accept poetry’s implicit claim on our emotions and thoughts. It’s the question of self-consciousness that is the most interesting part of Lerner’s book. Samuel Coleridge wrote that genius is the ability to hold two contradictory thoughts in your head at the same time and it is this problem that bedevils Lerner. Is poetry possible at all, he asks?

In particular, Lerner asks, will there always be an unbridgeable gap between the poet’s conception of the poem and the poem itself as s/he writes it? And as the public receives it?

Poetry is so overloaded by our expectations that no poem can possibly live up to them; every poem is, to greater or lesser extent, a failure because it cannot achieve the Platonic Ideal of the poem. Lerner has some acute remarks about how Keats and Emily Dickinson created new forms precisely because they were so antipathetic to how poetry was being written in their time: “The hatred of poetry is internal to the art, because it is the task of the poet and poetry reader to use the heat of that hatred to burn the actual off the virtual like fog.”

Hatred is Lerner’s word and he is entitled to it. I suspect he uses it because what he really means is Love, a word that is not astringent and cleansing enough for him; he writes:

Thus hating poems can either be a way of negatively expressing poetry as an ideal—a way of expressing our desire to exercise such imaginative capacities, to reconstitute the social world—or it can be a defensive rage against the mere suggestion that another world, another measure of value, is possible.

Lerner’s real enemy is the complacency of people who don’t think and feel as deeply as he does, who don’t burn with his own “hard, gemlike flame,” to use Victorian aesthete Walter Pater’s phrase, a flame that burns away all the dross.

I am not advocating for the mediocrity of culture or that we tolerate the shoddy when I say that Lerner’s conclusion, however admirable in the abstract, is simply untenable and impractical. In the first place, most of life is mediocre and shoddy, so there’s that to factor in. The other thing is that the dilemma he highlights—the inability to realize the ideal of poetry in the written poetry itself—is important theoretically or philosophically but completely unimportant in terms of how life is lived, especially in the work we do.

There is such a thing as too much self-consciousness, and Lerner has it. The point is to reach Coleridge’s toleration for two contradictory things. In physics, the Newtonian world of appearance coexists with the unknowability of the quantum world—a contradiction that doesn’t affect our ability to get around in real life. So in poetry we should accept the impossibility of the poem by writing poems.

If we can’t attain Coleridge’s Zen-like balance, do what Emerson suggested and take drugs or alcohol to eliminate the gap between what we want to say and what we can say given the limits of form, history, language, privilege and all the other restrictions that supposedly make writing impossible. Lerner comes back again and again to Whitman because he basically can’t understand how Whitman can embody the contradictions that he celebrated both in his own person and in the irreconcilability of the American individual with American society. My suggestion is that Whitman simply didn’t think about these things: “So I contradict myself.”

That blithe “So” is so dismissive. . . so Whitmanesque. He was too busy writing poetry that explored the very thing that bothers Lerner: the irreconcilability of opposites.

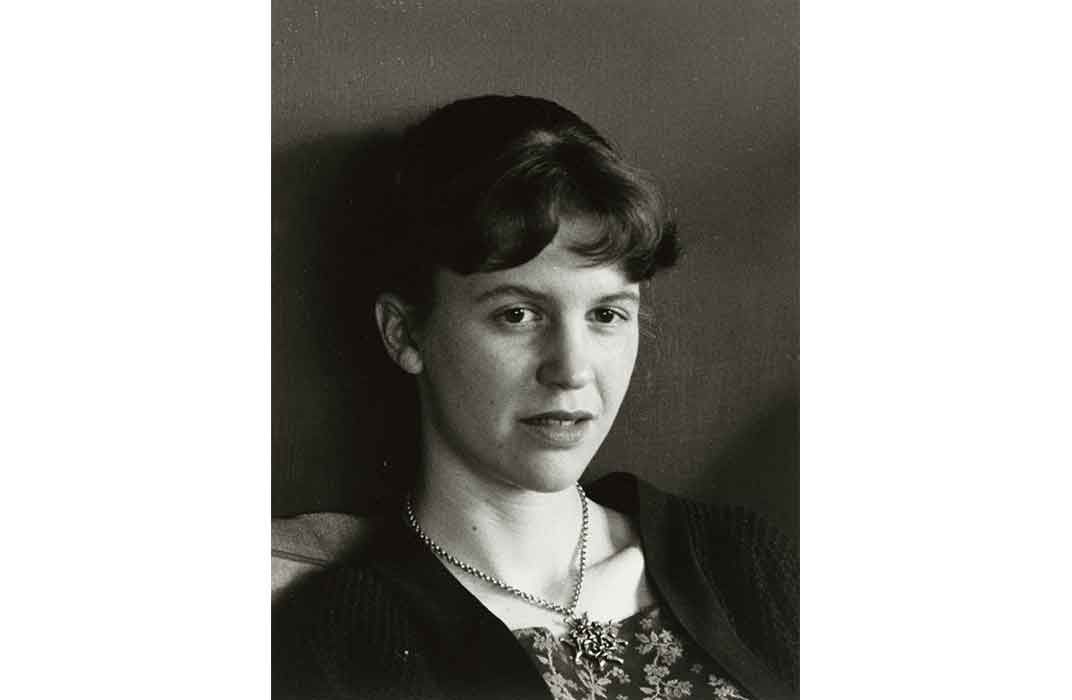

I think that The Hatred of Poetry will be salutary if the conceit of Lerner’s title draws people in and makes people think about the demands that we place on poetry. For instance, Lerner is sharp on the relationship between poetry and politics as in how some critics privilege “great white male poets” like Robert Lowell as universal while they argue that Sylvia Plath speaks only for a narrow segment of women. More generally, we need to think about how we reflexively use Poetry (with a capital “P”, of course) as a substitute for real human feeling and real engagement with the world.

It’s not that people hate poetry. It’s that people expect and demand too much from it.

It is the highest form of utterance in our society, and it can’t bear the weight of what we have invested in it. We use poetry when words fail us.

But for the poets themselves, the task is simple. Just write poems. There’s no way around it. In the fallen world in which we live, there’s no way out of the tasks that the world demands of us. If we are inadequate to those tasks, why would you expect anything else? We might and should expect better, of course, not for any other reason but for the intrinsic pleasure of making something out of the ordinary, maybe not a Grecian urn but just. . .something better.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)