Smithsonian Curators Help Rescue the Truth From These Popular Myths

From astronaut ice-cream to Plymouth Rock, a group of scholars gathered at the 114th Smithsonian Material Culture Forum to address tall tales and myths

:focal(335x190:336x191)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/e2/3ee2ccf4-092c-414d-9723-bbff8ca2850a/myths.jpg)

Hollywood can't resist depicting Dolley Madison saving a portrait of George Washington from the British army. Museum visitors love to gobble up the sticky confection known as astronaut ice cream, and Plymouth Rock has become a symbol of the national narrative, but like everything else, it’s complicated. Like a game of telephone, stories that are part myth and part truth circulate from source to source, becoming less accurate with each telling. These stories have evolved lives of their own.

“The problem with myth is that it obscures and changes what you see,” explains Kenneth Cohen, a curator at the National Museum of American history. “Myth transforms mere inaccuracy into a false, but memorable, story that explains something much bigger than the facts it obscures.”

At a recent gathering, Smithsonian scholars set a course towards clearing up a few common historical misconceptions, revealing facts that have long been obscured by myths, and in the process, providing a fuller context to history. The occasion was a curatorial gathering for the Smithsonian’s 114th Material Culture Forum, a quarterly event that provides researchers with an opportunity to share information with their colleagues and maintain a sense of scholarly community across the Smithsonian. Committed to finding and exposing evidence, the curators shared their research to build on interpretations of the past and plans for the future. Below are some of the major takeaways:

First Lady Dolley Madison Did Not Act Alone

Robyn Asleson, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, says the story of Dolley Madison rescuing the George Washington portrait is often told as follows: To save the famed portrait—a copy of the original version that had been painted by Gilbert Stuart—during the 1814 British invasion of Washington, D.C. and the burning of the White House, Dolley Madison cut the portrait from its frame, pulled it from the wall, tucked it under her arm, and fled to safety. She also grabbed the Declaration of Independence, securing it in her carriage.

Within days and weeks of the event, the heroic story began to circulate and each storyteller added embellishments. Asleson was quick to point out the fallacy. “The original [Declaration of Independence] was kept at the State Department, not the White House,” she says. “It was actually a civil servant, Stephen Pleasanton, who removed it—along with the Constitution and the Bill of Rights—just prior to the British army’s arrival in Washington D.C.”

As for the story of the portrait, the source of the myth is harder to trace. Several people who had been in or near the White House that day recounted their own version of the events, often taking credit for the rescue. Asleson has traced the narrative as it was retold throughout the period. Madison herself published the first account, based on a letter she wrote to her sister reportedly as the rescue was in progress. She describes the scene: “Mr. Carroll has come to hasten my departure, and is in a very bad humor with me because I insist on waiting until the large picture of Gen. Washington is secured, and it requires to be unscrewed from the wall. This process was found too tedious for these perilous moments; I have ordered the frame to be broken, and the canvass taken out.”

Others are also credited. Former president Andrew Jackson insisted the rescue had been carried out by John Mason, brigadier general of the District of Columbia militia and son of George Mason. Businessman and politician Daniel J. Carroll insisted that it was his father, Charles Carroll, who had rescued the portrait. Even Madison herself spoke up again to re-emphasize her role in the saving of the portrait.

It wasn’t until a few of the unnamed servants and enslaved people spoke out for themselves, that their stories emerged. “The crucial efforts of the French steward, the Irish gardener, and several enslaved African Americans—only one of whom was ever named—cast the story in a different light,” says Asleson. “In the end, this celebrated tale of American patriotism turns out to revolve around the heroic actions of a group of immigrants and enslaved people.”

Life in Space Includes Some Earthly Delights

Jennifer Levasseur, museum curator at the National Air and Space Museum, says myths about astronaut equipment permeate her research on the physical needs of astronauts as they work and live in space. Their needs are the same as they are on Earth, she says. They have to eat, drink, sleep and go to the bathroom. But, in the environment of microgravity, the execution of these human functions requires a few adaptations.

Velcro is needed to keep things in place, a specially designed cup is needed for coffee, and toilet suction is needed to help remove the waste and flush it away. “How those activities are even slightly changed by space is almost magical in its description and difference,” explains Levasseur. “When the answers to our questions are ordinary, it tends to fascinate.”

Only a small fraction of Earth-bound humans—530 people, to be exact—have been to space. NASA doesn’t retain much in the way of historic documentation, says Levasseur. Some items NASA uses are simply off-the-shelf items; they use pencils, felt-tip pens and even a pressurized ink cartridge by the Fisher Pen Company that works in space. “These are things we use all the time, they seem innocuous to some degree, and don’t take the years and decades to develop as we see with rockets or spacecraft,” says Levasseur.

Levasseur debunked, or confirmed, a few familiar space equipment myths. Did astronauts drink Tang? Astronauts drank a variety of powdered and rehydratable drinks. So in theory, they probably did drink Tang, a product that capitalized on the association with skillful marketing and advertising.

Another common question is whether astronauts ate the foam-like freeze-dried ice cream that is sold to hungry visitors in museum gift shops. Levasseur says that it was tested, but not used in space as the crumbs produced would have clogged up the air filters. Instead, astronauts eat regular ice-cream. She did confirm that astronauts use “space diapers,” though not the whole time they’re in space. “The ‘maximum absorbency garment,’ as they are called, is really the most effective, simplest tool for containing waste under a spacesuit,” she says.

These stories, says Levasseur, emerge from trying to imagine the unimaginable. “Myths about the materials themselves start in this moment of attempting to connect, wanting to comprehend something happening in a strange place as something innately familiar,” says Levasseur.

The Story of Plymouth Rock Obscures True Facts of the Colonial Period

Kenneth Cohen, from the American History Museum, dedicated his session to tracing the myth surrounding Plymouth Rock to its roots, not merely to debunk it, but to unveil the true story that the myth has obscured for centuries.

According to the most-often told version, 102 prosecuted English colonists, seeking religious freedom and a land of new beginnings, fled to America in 1620, disembarking at an enormous outcropping—Plymouth Rock. Cohen points out that only half of the passengers formally belonged to the religious sect of Separatists known today as "the Pilgrims," and given the sandy shores where they arrived, their first steps probably were taken on a beach.

Early historical records rarely reference a rock. The importance of Plymouth Rock emerged as a grand narrative in the origin story of United States during the period of the American Revolutionary War. The rock, Cohen argues, reflects an aesthetic movement that dates back to the late 1700s and early 1800s—the 'sublime.’ “It was an approach to rhetoric and art that emphasized grandeur and scale as ways to emotionally move people,” says Cohen on the meaning of the Sublime. “Originally depicting moments and places where humanity and divinity meet, it evolved into a mode that emphasized nature's power through scale, force and harshness.”

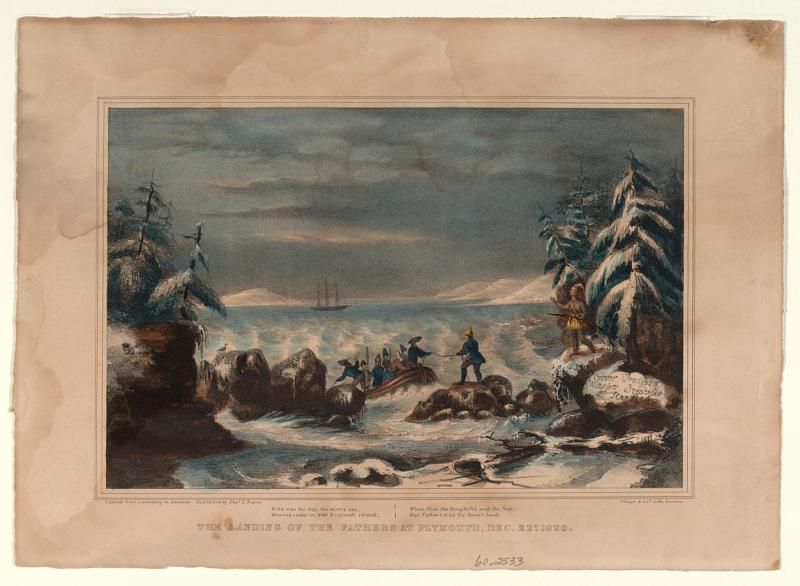

In artistic reinterpretations like Michel Felice Corné’s Landing of the Pilgrims (1807) and Henry Sargent’s version a decade later, the sandy beaches are transformed into rocky cliffs. These rendered scenes were popular because they framed the Pilgrims as heroes taming and cultivating a harsh wilderness. The reality is that the English colonists disembarked on a beach where they could comfortably refresh and resupply. There chosen landing was a matter of practicality–the settlement had been a Wampanoag village that offered cleared land and access to food staples.

By attaching all of these symbolic motifs to a rock, it became the historical icon that mythologizes the arrival and places the focus on the landscape. “It encapsulates Euro-American historical memory that this lone Rock, not the shoreline, not the fields, and above all not the people who already lived there, are what they made the focus,” explains Cohen. “To combat the myth, we’ve got to push our visitors so they can look up over the top, and see all the sand, the fields, and above all, the Native peoples who have been busting this myth for centuries already.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Image_from_iOS.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Image_from_iOS.jpg)