Smithsonian Elevates the Frequently Ignored Histories of Women

For many, the personal—tea cups, dresses, needlework and charm bracelets—really was political. A new book tells why

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cc/1d/cc1d327f-ce95-45cf-8c1d-abb2974e4867/womenshistoryartifacts.jpg)

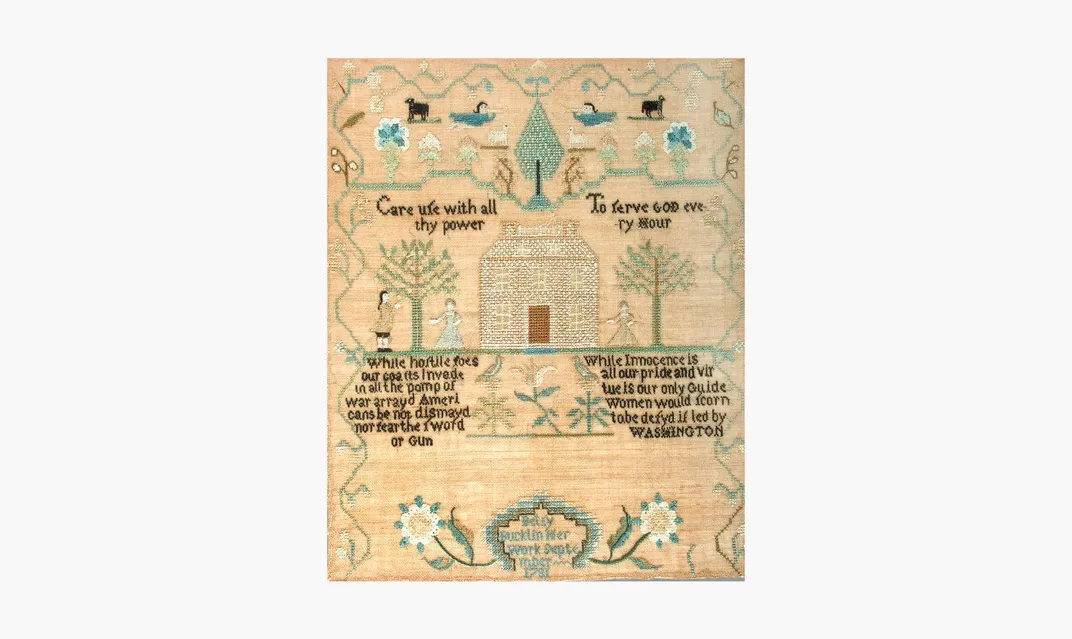

Historians remember September 1781 as the month the Continental Army began its last major land battle, bolstering the rebel Americans’ morale and breaking Britain’s will to fight. But something more prosaic happened that month when 13-year-old Betsy Bucklin sat down with needle and thread to work on her sampler. She was not alone: Countless girls of the era stitched samplers to show off their most advanced needlework skills. As Bucklin sewed in her Rhode Island home, she worked the delicate silk threads into the shapes of animals, trees, flowers and people.

Upper-class girls like Bucklin did not go to war. Instead, the war came to Bucklin’s sampler as she stitched. “While hostile foes/our coasts Invade/in all the pomp of war arrayd Americans be not dismayed nor fear the sword or Gun,” she sewed. “While innocence is all our pride and virtue is our only Guide Women would scorn to be defyd if led by WASHINGTON.”

Did Bucklin write the patriotic verse herself, or did she stitch it at the behest of her sewing teacher? The answer is lost to history. But Bucklin’s sampler still exists today, a testament to past girlhood and the passionate sentiments held by women during the Revolutionary War.

Bucklin’s handiwork is one of the hundreds of artifacts featured in Smithsonian American Women: Remarkable Objects and Stories of Strength, Ingenuity, and Vision from the National Collection, out now from Smithsonian Books.

Packed with ordinary objects made and used by American women, the book considers their contributions to the nation’s history through the lens of the things they invented, created and owned. It’s a sampler unto itself, taking a wide-ranging tour through the Smithsonian Institution’s massive collections and pulling out everyday items with extraordinary tales to tell.

An axe, a cup and saucer, a charm bracelet and a tea-length gown might seem ho-hum if not for their origin stories. But the book provides context that justifies their inclusion in the national collection and casts them in a new light—as part of American women’s legacies of agitation, resistance, struggle and change.

The axe was carried by a reform-minded member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, a coalition that thrust women into political activism on an anti-alcohol platform, in the 1870s. The cup and saucer were created in the 1930s by Belle Kogan, a pioneer of industrial design. The charms were chosen by suffragist and Equal Rights Amendment author Alice Paul, who added a new one to the bracelet each time a state ratified the ERA during the 1970s. And the gown was worn at the 1959 high school graduation of Minnijean Brown, one of the Little Rock Nine, when she accepted her diploma.

Smithsonian American Women: Remarkable Objects and Stories of Strength, Ingenuity, and Vision from the National Collection

Smithsonian American Women is a deeply satisfying read and a must-have reflection on how generations of women have defined what it means to be recognized in both the nation and the world.

Brown was among the nine black students who were the first to attend all-white high schools during the desegregation battles that roiled the South after Brown v. Board of Education declared school segregation unconstitutional in 1954. But she didn’t graduate from Central High School; after being expelled for defending herself against the attacks of racist students, she completed her high school education in New York. (A suspension notice from one of the times Brown fought back against white students’ sustained harassment is included, too.)

“With its sheer white overlay and delicate floral pattern, the dress belies the difficult—and at times ugly—journey of attending and graduating from an integrating high school in the 1950s,” writes curator Debora Shaefer-Jacobs of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Synthesizing more than 400 years of American women’s history into 248 pages is an ambitious and nearly unachievable task. Curator and historian Michelle Delaney, the project’s director, acknowledges the challenge. “Curators and archivists suggested over two thousand objects for this volume,” she writes. “We are seeking to restore a history too frequently ignored.”

A focus on historical resistance, reform, protest and backlash helps break through what might otherwise be a historical logjam. So does the book’s attempt to give women of color their due. The compendium goes beyond a focus on famous women of color (think: Sojourner Truth and Oprah Winfrey) to incorporate the lives of less-celebrated women, like Mississippian artisans who created clay effigies of divine women between 1400 and 1600 and Natalia Flores, a Mexican American Chicagoan whose quinceañera gown is included.

Designed to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, the volume is crammed with 135 essays by 95 Smithsonian authors and images of 280 artifacts from 16 Smithsonian museums and archives. But the collection, produced by the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative, “Because of Her Story,” goes beyond statistics. Taken together, the artifacts and essays breathe life into ordinary and extraordinary moments in American women’s lives.

At first, Delaney says, the question of how to do justice to American women’s lives in a single volume seemed overwhelming. “It took us a long time to break free of a really patriarchal chronology,” she says. Instead of focusing on American wars and politics, says Delaney, the book’s editors tried to tell a story through the lens of American women’s everyday lives—stories that intersected and ran parallel to the nation’s unfolding story. “We talked a lot about how the personal is political,” says Delaney. “There is something to be said for how each personal life is affected by the state of the nation.”

Tellingly, the book’s most powerful pages are the ones that show women in their most personal pursuits: the activism of a grieving mother, the labor of an entrepreneurial cook, a persecuted sculptor’s masterpiece, a marginalized midwife ready to roll up her sleeves and get to work. Mundane, world-changing and everything in between, each artifact speaks to lives that, stitched together, track the trajectory of American women and the nation they shape, serve and sometimes struggle against.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erin.png)