Smithsonian Scientist and a Reef-Diving Grandmother Team Up in Discovery of New Hermit Crab

A new species of hermit crab is named to honor her 7-year-old granddaughter Molly

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d5/d2/d5d2f1bc-7faa-4e51-9d17-264c66a4dd55/oo_118855.jpg)

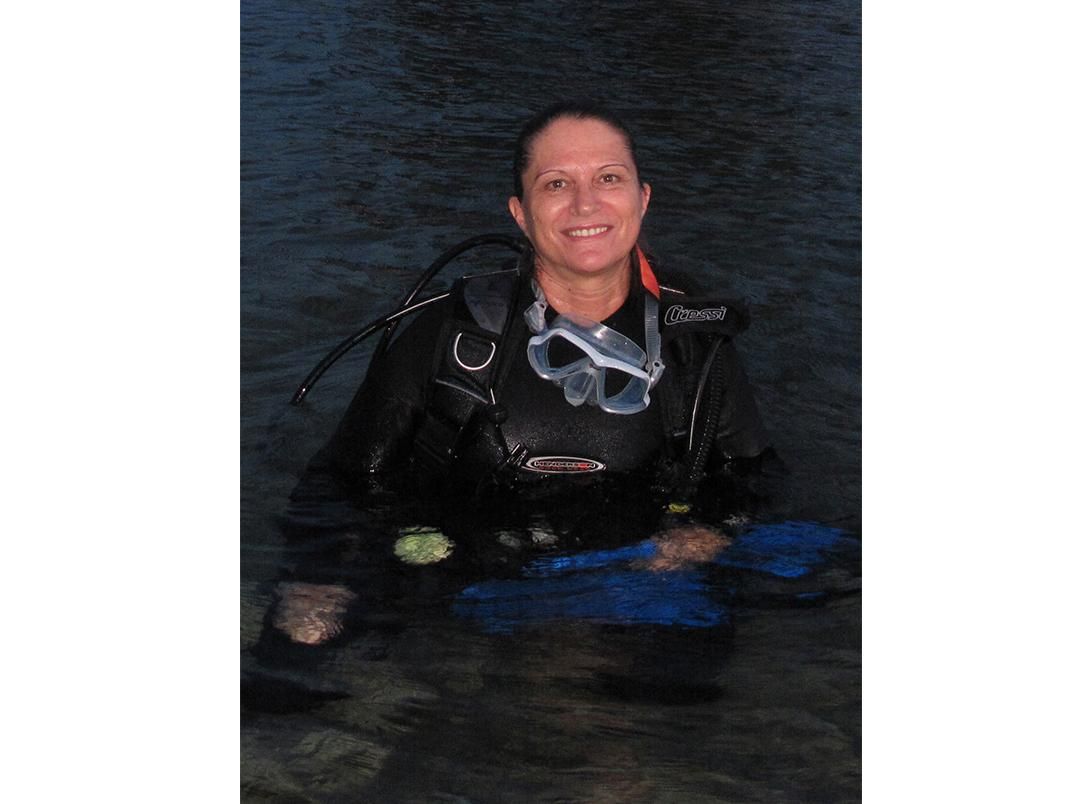

On a nighttime SCUBA dive in waters off of the Caribbean island of Bonaire, Ellen Muller moved in close to photograph a flaming reef lobster with a red light that wouldn't scare animals the way that a standard white light might. Little did she realize at the time that besides expertly framing and lighting her picture of a brightly colored lobster, she had discovered a completely unknown species of hermit crab lurking in the background of her photograph.

After her dive, Muller looked at the image of the lobster on her computer screen and realized that the tiny crab behind it wasn't a species that she recognized from her many other dives in the area. She hadn't even noticed it while taking the picture.

The new species, which Muller has given the common name of “candy-striped hermit crab” due to its red and white stripes, has just been described in a paper by Rafael Lemaitre, a research zoologist at Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History and the curator of decapod Crustacea. The new species has been given the Latin name, Pylopaguropsis mollymullerae. At Muller's request, Lemaitre named the species after her granddaughter, Molly, “to inspire her to appreciate and protect the marine life once she grows up,” Muller says. “She's seven so she doesn't quite understand it all but she's very happy about it.”

“Ellen Muller sent me the first photograph and I realized right away it was something that had not been reported,” Lemaitre says. “The morphology was something that was not common.”

The colors and the claw shape of this thumbnail-sized crab were unlike anything that Lemaitre, a hermit crab expert, had ever seen before. He realized that this was probably a new species but in order to be certain, he would need better photographs and then physical specimens.

Muller is an American ex-pat who has lived since 1980 on Bonaire, a popular tourist destination in the Dutch Antilles, where thousands of divers each year take underwater photos and videos of creatures living among the easily accessed coral reefs. In 2001 Muller took up SCUBA diving and underwater photography. What sets Muller apart is her willingness to dive at night and look very closely for the tiniest creatures.

“I love looking for unusual and cryptic creatures that most people would go right by,” Muller says. “I dive with a magnifying glass. I dive a lot at night to see things that most people don't see.”

Trying to find the exact same spot with the exact same lobster den and the same tiny hermit crab seemed to be an order of magnitude more difficult than finding a needle in a haystack. But Muller pulled it off and then started to find the candy-striped crabs in other places as well.

“I saw some last night,” Muller says. “I found them at a couple of different dive sites. I've gone back many times to see the first ones that I found. A whole colony was there.”

Typically, Muller has seen the hermit crabs in crevices within underwater dens shared by lobsters and moray eels. The animals seem to tolerate each other and may benefit from each others presence.

“I did see one with a spotted moray eel once that was injured,” Muller says. “It seemed like the candy-striper was picking something off the skin of the spotted moray eel, which was interesting.”

Lemaitre and Muller have speculated that the candy-striped hermit crab may be working in a mutually beneficial partnership with the other species, perhaps removing parasites from the larger creature. There is not enough evidence yet to say for certain.

“They may benefit from these little droppings of things,” Lemaitre says. “Hermit crabs will eat anything. They are scavengers. I wouldn't be surprised if they are hanging around the moray eels because there is food available to them.”

The strangest thing about this crab is the unusual shape of its dominant claw. Lemaitre says that a lot of hermit crabs have strangely shaped claws but “this one is particularly odd because it looks like a scoop.”

“You usually have a lot of features on the top of a pincher or claw, but the bottom, not so much,” Lemaitre says. “Because the bottom is close to the body when they retract. . . It could be used as a scoop but it's hard to say. It's one of those intriguing things in nature.”

As part of the process of documenting the new species, Lemaitre needed Muller to obtain legal permits to collect six specimens and mail them to him in the U.S. He chose one as the type specimen, which becomes a sort of official definition of what a given species looks like and to which other species will be compared. Lemaitre then wrote a careful description of the unique features of the crab, especially of the unusual claws.

None of the hermit crabs have been dissected yet. New species of bacteria and parasites may still be waiting inside of them for another taxonomist to discover.

Ellen Muller already has another species named after her. Astoundingly, this is the second species that Muller has personally discovered as an amateur diver. In 2007 she identified Trapania bonellenae, a type of nudibranch commonly referred to as a sea slug.

Lemaitre is excited about the new species but this isn't his first time, either.

“Over my career I've described maybe a hundred, probably,” Lemaitre says. “One of my main jobs here is to study biodiversity. This is what collections are all about. . . . Because you can look at everything that has been collected in the world right in front of you.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)