The Smithsonian Wants You! (To Help Transcribe Its Collections)

A massive digitization and transcription project calls for volunteers at the Smithsonian

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3c/48/3c48f707-6763-45a3-b98e-d364c13882e4/williamdalldiaryedit.jpg)

Many myths surround the Smithsonian Institution’s archives—from legends of underground facilities hidden beneath the National Mall to rumors of secret archaeological excavations. One underlying truth persists amid these fallacies: the Institution’s archives are indeed massive. Preserving these collections in a digital age is a gargantuan task, especially when it comes to handwritten documents. Ink fades with time, and individual scrawls sometimes resemble hieroglyphics. It could literally take decades.

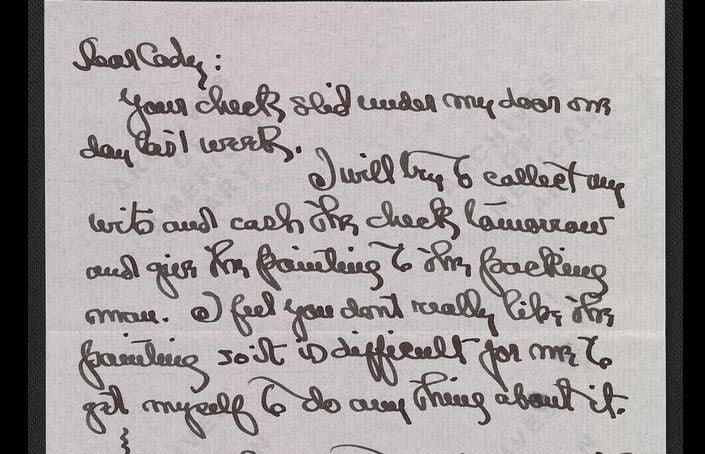

The Smithsonian, instead, aims to shorten that timeframe with the help of anyone with an Internet connection. After about a year of testing with a small group of volunteers, the Smithsonian opened up their Transcription Center website to the public last month. Today, they issued a called for volunteers to help decipher everything from handwritten specimen tags to the personal letters of iconic artists to early U.S. currency. “For years, the vast resources of the Smithsonian were powered by the pen; they can now be powered by the pixel,” Smithsonian Secretary Wayne Clough said in a statement.

Though many specimen and documents have been digitized, handwriting can be tricky. The goal is to crowdsource the transcription of material that a computer just can’t decipher. By opening the transcription process up to the public, they hope to make those images not only accessible, but searchable and indexable to researchers and anyone else who’s interested across the globe. “These volumes open a window on the past and allow those who lived in the past to speak directly to us today,” says Pamela Henson, a historian in the Smithsonian’s Institutional History Division.

During the project’s year of beta testing that began June 2013, 1,000 volunteers transcribed 13,000 pages of archived documents. But crowdsourcing can come with a potential for human error. To avoid any typos or discrepancies, multiple volunteers work on and review each page, and a Smithsonian expert verifies the work for accuracy. Transcription is a team effort, as project coordinator Meghan Ferriter has found. “We have a community that’s developing,” says Ferriter. “Volunteers talk to us and to each other on the transcription site and on social media.”

The move is part of a trend among archive facilities. The New York Public library crowdsourced the digitization of its extensive restaurant menu collection. The U.K. National Archives asked for help earlier this year in transcribing diaries of World War I soldiers. It’s not necessarily new to the Smithsonian either. “The Smithsonian has relied on the kindness of strangers to assist with its work since the 1840s, when volunteer weather observers began to send climate data to our Meteorological Project,” notes Henson. “In some ways we are continuing that tradition.”

Volunteers have completed a total of 141 projects, including Mary Anna Henry’s Civil War-era diaries (which include the moment she heard of Abraham Lincoln’s death). The speed that crowdsourcing facilitates has already generated some impressive results: 49 volunteers transcribed 200 pages of correspondence between the Monuments Men in a week.

For those interested in immersing themselves in a bit of history, ongoing transcription work spans a wide variety of fields:

- A project launched today aims to transcribe a report by archaeologist Langdon Warner, one of the Monuments Men and the inspiration for Indiana Jones. It already has 39 people willing to help tackle the 234-page document.

- Mary Smith’s Commonplace Book Concerning Science and Mathematics offers a look inside the mind of a virtually unknown female amateur scientist from the late 1700s. Smith’s work is handwritten and features summaries of scientific discoveries of the day, as well as her own experiments and data collections.

- Those looking for a challenge might try their hand at transcribing the English-Alabama and Alabama-English dictionary. Compiled from 1906 to 1913, the massive work includes thousands of vocabulary terms. Volumes three and four still need some work.

- Renowned 19th-century clockmaker Edward Howard’s astronomical regulator is housed in the National Museum of American History. A transcription project focused on his business ledgers show the far reaches of the Boston clockmaker’s business.

- Another project is in the process of photographing and deciphering the tags on 45,000 bee specimen. Volunteers enter metadata for each bee imaged on where and when the specimen was collected. Such a massive dataset could prove useful to researchers studying bee populations today.

Once finished projects get the Smithsonian’s stamp of approval users can download them through the collections website or the transcription center. As the Smithsonian digitizes more and more of its collections, the plan is to make them available online for volunteers to transcribe and historical scholars and enthusiasts to enjoy.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2014-01-27_at_12.05.16_PM.png)