Sounds of 1950s New York City and More from Folkways Magazine

Under a new editor, the latest issue features a day in a dog’s life, audio postcards from around the world and more

![]()

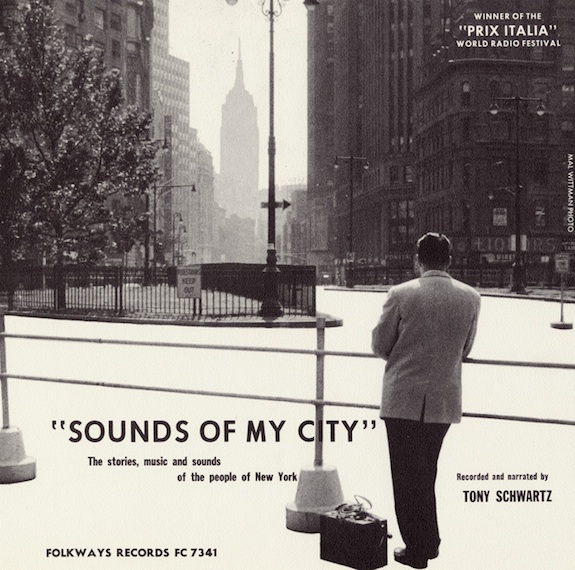

A cover for a 1956 album of recordings by Tony Schwartz. Photo by Mal Wittman, courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways

Ever wondered what New York City sounded like in the 1950s–from the point of view of a dog? So did Tony Schwartz, a sound recordist living in the city who sought to capture all the many sonic fragments that made up his every day experience. His piece, centered on his own dog, Tina, aired as part of a CBS radio workshop and eventually found its way to the Smithsonian Folkways label. Now Meredith Holmgren, who recently became editor of Smithsonian Folkways Magazine, has highlighted the charming bit of audio in her first issue, “Sounds and Soundscapes.”

“We have a great collection of sounds and soundscapes that have not been highlighted,” says Holmgren. “In fact, Folkways is one of the earliest labels in history to start gathering these recordings; we have office sounds, train sounds, a whole science series.”

Organized around that idea, the Fall/Winter issue includes a feature on sound recordist Tony Schwartz, an opinion column about the idea of a common sound space and a piece about the first time museum content was paired with sound. There’s also an artist profile about Henry Jacobs, who Holmgren describes as, “one of the early pioneers in using technology to imitate sounds and to create synthetic rhythms and to work in ethnomusicological broadcasting.”

All of this comes from the riches of the Folkways collection, the gift that keeps on giving. Moses Asch first founded the label in 1948 in New York City with the mission to “record and document the entire world of sound.” His efforts, as well as those of his colleagues, helped create an invaluable database of recordings that continues to provide the raw material for new releases for the Smithsonian Institution Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage in Washington D.C. , which acquired Folkways Records in 1987 after Asch’s death.

Established in 2009, Smithsonian Folkways Magazine is meant to bridge the space between academic journals and music journalism. Holmgren says, “Often scholarly music journals, you can’t actually listen to the music. You’ll read hundreds of pages about the music but you can’t hear it. It’s the same with music journalism, although music journalism tends to be a little more photo or image-friendly and so we thought that an online only multimedia publication was really the way to go.”

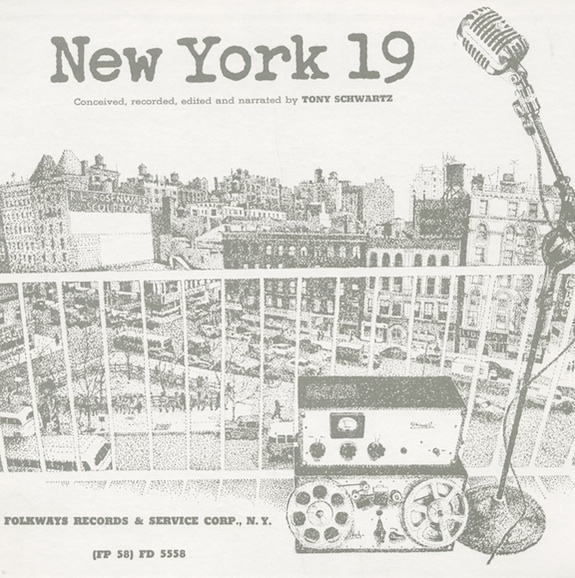

Another Schwartz album from 1954. Illustration by Robert Rosenwald, courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways

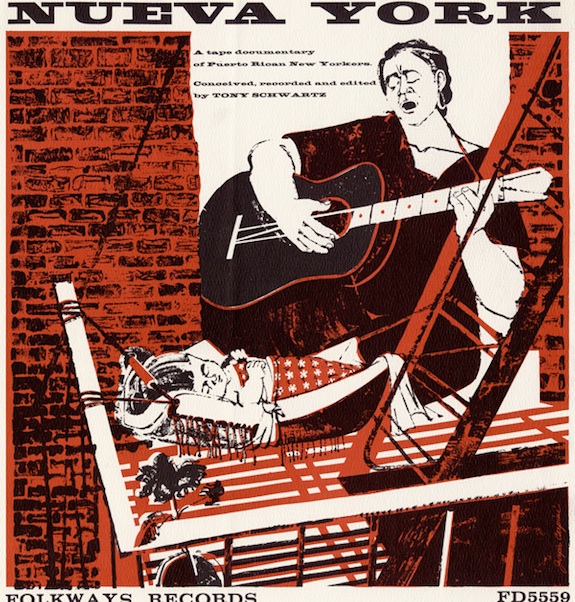

From the 1955 Nueva York album. Cover by Joseph Carpini, courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways

The World in My Mail Box, from 1958. Cover by Wim Spewak and Joseph Carpini, courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways

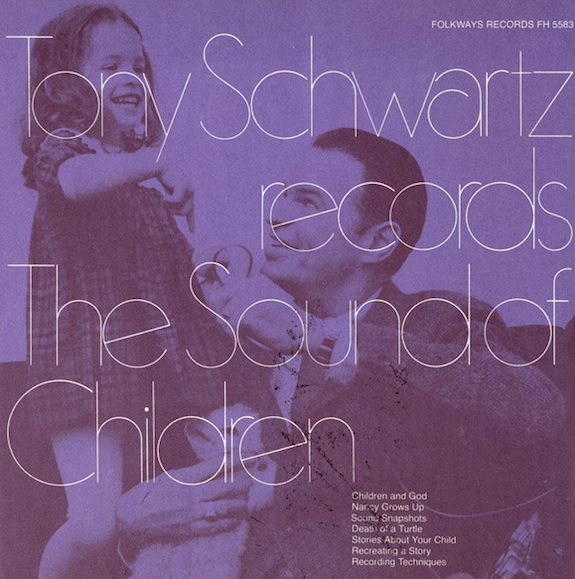

Children were the subject of this 1970 album. Design by Ronald Clyne, courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways

It also gives her a chance to publish unreleased material, including Schwartz’s Out My Window, a collection of sounds heard from his new York City apartment as he sits by his back window. “Looking at it in the present,” she says, “it’s a very unique documentation of cityscapes and human interaction only a few decades ago. He was documenting things that were underrepresented or neglected.”

Projects like his The World In My Mail Box looked beyond the city as well. Collecting sounds sent to him from all around the world, Schwartz became “the best pen pal ever,” says Holmgren. “He didn’t travel much because he had agoraphobia, which he spun in a way that became an advantage to him actually; looking in great detail to things that were around him,” she explains. “World In My Mailbox is this kind of interesting collection of sharing recordings with people and places where he knows he will never go.”

Avid sound collectors like Schwartz and Folkways Records founder Moses Asch, provide the perfect analogy for the magazine’s mission as well: to highlight the sonic diversity of the world we live in and share it with as many people as possible. Holmgren says, “I really hope that the magazine can contextualize our collection, talk a little bit about the history of the recordings, the context in which they were made, but also highlight new music that other people may not know about.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)