Medicine Creek, the Treaty That Set the Stage for Standing Rock

The Fish Wars of the 1960s led to an affirmation of Native American rights

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/36/2936cd33-4d3b-4e7a-9c8e-9deed65593ea/nmai-000004.jpg)

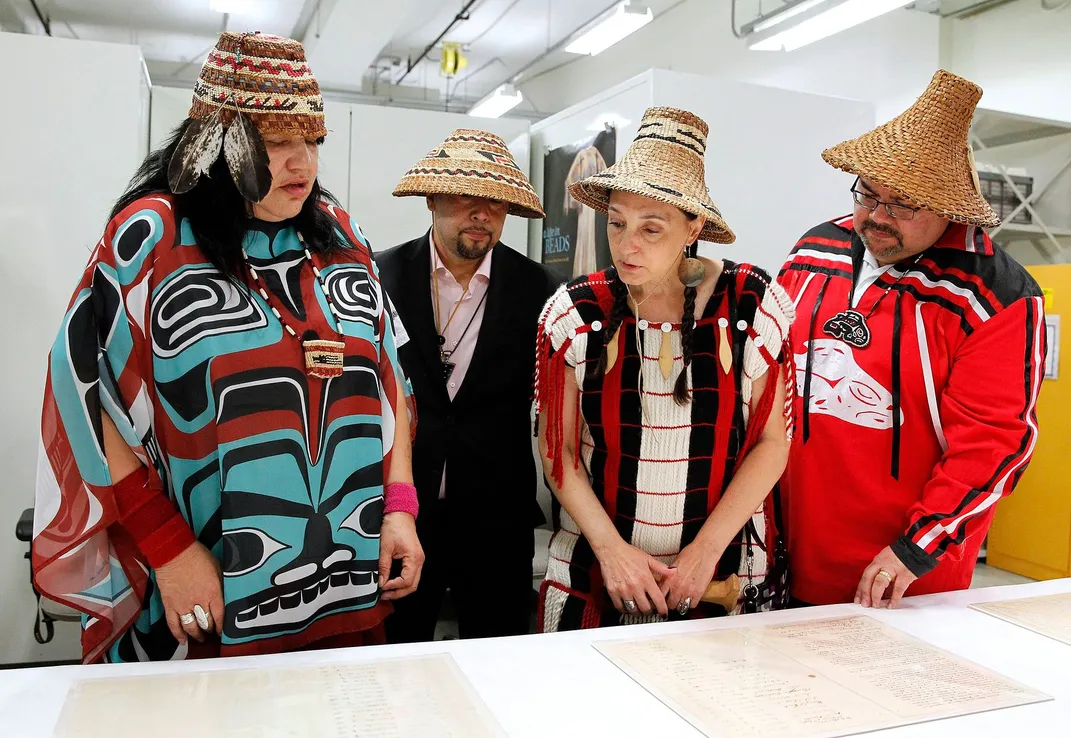

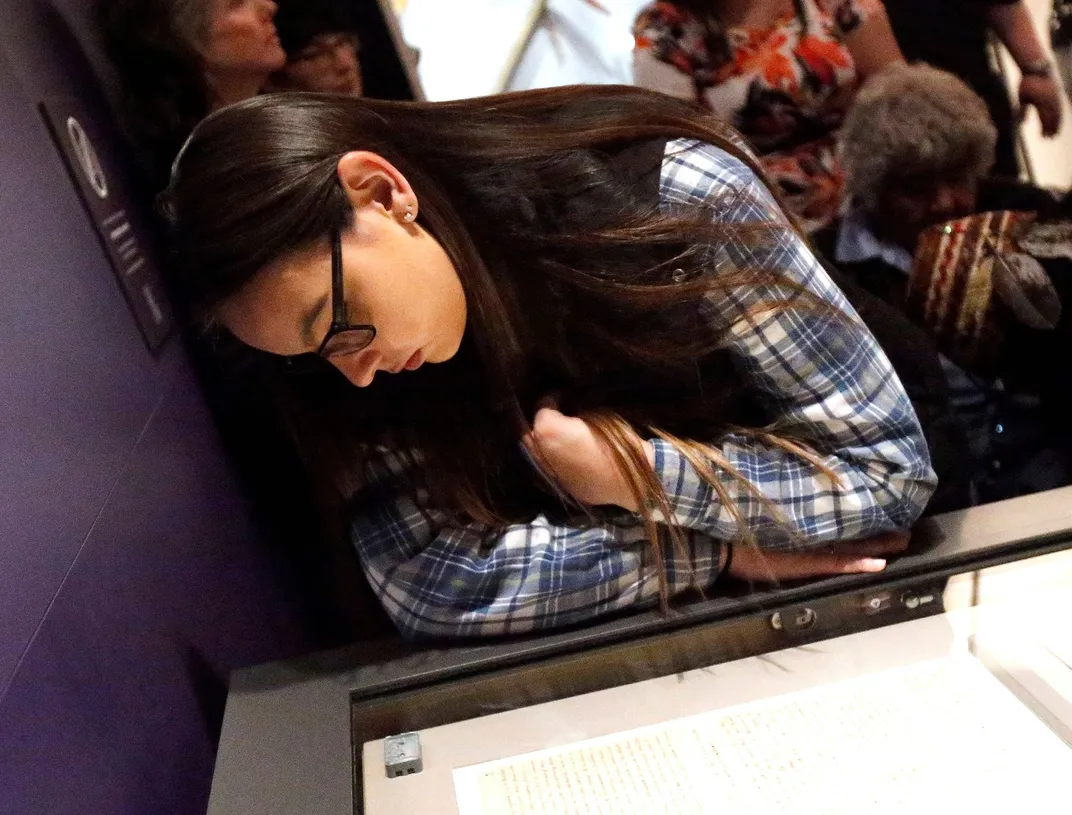

In a darkened gallery at the National Museum of the American Indian, Jody Chase watched from her wheelchair as the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek—illuminated in a sealed wooden box topped with glass—was officially unveiled to a gathering of representatives from some of the signatory tribes. Songs and chants were performed, and speeches made.

Then, as the group was about to break up, Chase, a member of the Nisqually tribe, which is currently located near Olympia, Washington, stood up and walked over to the box, leaned in and began singing softly; periodically her arms made sweeping motions over the glass. Soon, she was weeping quietly, still singing and moving her arms.

“I was asking for prayer for the protection of it so that when it’s out to the public’s eye it will be protected,” says Chase.

“Our ancestors fought for these rights,” she says. “We have to continue to fight for these rights. We have to teach our children and our grandchildren of the history, so that they will know what they need to respect and honor.”

It seemed like a fitting end to the solemn ceremony, which marked the first time the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek has been on public view. This treaty is the sixth in a series of nine important treaties made with Indian nations to go on display as part of the “Nation to Nation” exhibition at the museum. The Treaty of Medicine Creek, one of 370 ratified Indian treaties held at the National Archives and Record Administration, will remain on view through September 19. The brittle pages of the six-page handwritten document, on loan from the National Archives, recently underwent conservation measures for display, and is protected behind UV glass in a specially constructed, secured case.

Like the majority of U.S. government treaties with Native Americans, Medicine Creek allowed for the “purchase” of tribal lands for pennies on the dollar. But unlike the majority, Medicine Creek guaranteed nine nations, including the Nisqually, Puyallup and Squaxin Island nations of the Puget Sound area in western Washington the rights to continue to hunt and fish in their “usual and accustomed grounds and stations.”

The Nisqually, Puyallup and Squaxin Island nations view those six handwritten pieces of paper as sacrosanct.

The Medicine Creek treaty arose out of a series of treaty councils in the winter of 1854 held by the new governor of Washington Territory, Isaac Stevens. As in other areas of the West, white settlers and prospectors wanted the land occupied by the Indians. Stevens was negotiating the terms and eyeing some 4,000 square miles of fertile lands around Puget Sound and its tributaries, tribal home to the native Indians.

Scholars are somewhat divided on who came up with the idea of offering fishing and hunting rights in exchange for the land. Mark Hirsch, a historian at the museum, says it is clear that a month before any sit-downs with the tribes, Stevens’ notes indicate he had decided that guaranteeing traditional hunting and fishing rights would be the only way the Indians would sign an agreement. The language was drafted before the treaty councils, says Hirsch. “They’ve got it all written out before the Indians get there,” he says.

It is an agreement that is continuously tested. Today, the Medicine Creek treaty rights are under threat again from a perhaps an unforeseen enemy: climate change and pollution, which are damaging the Puget Sound watershed and the salmon that breed and live in those rivers, lakes and streams.

“It’s tough because we’re running out of resources,” says Nisqually tribal council member Willie Frank, III, who has long been active in the modern-day fishing rights battle. “We’re running out of salmon, running out of clean water, running out of our habitat. What we’re doing right now is arguing over the last salmon,” he says.

The history of Indian treaties is littered with broken promises and bad deals. And even though Medicine Creek was disadvantageous in many ways, “it’s all we’ve got,” says Farron McCloud, chairman of the Nisqually tribal council.

Medicine Creek was selected for display at the museum in part because of the rights it guaranteed—and because of the fierce battles that have been fought to preserve those rights, says the museum’s director Kevin Gover, a Pawnee. “These rights are not a gift. They are rights that are hard-won, and they are rights that are well-defended,” he says.

“We recently saw at Standing Rock the activism around protecting tribal rights, protecting treaty rights,” he said at the unveiling. “Those of us who are my age remember the treaty fight in the Pacific Northwest. The tribes there did defend a quite obvious proposition—that these treaties remain in effect,” he says. “The rights they give are perpetual. And that the Indian Nations continue to exist.”

A treaty is a living, breathing document. And, like the U.S. Constitution, it sets the foundation for the laws of the Indian nations, which are one of the three sovereign entities in the United States—the others being the federal government and state governments.

“We’re conditioned to think of treaties as being bad,” says Hirsch. But they are critical for the signatory tribes. “They recognize tribes as nations—sovereign nations,” and treaties give those tribes nation-to-nation rights, says Hirsch. “That’s one of the elements that makes native people fundamentally different than anybody in the U.S.,” he says.

“Tribes make their own laws and state law may not interfere with that tribal political society,” says Robert Anderson, director of the Native American Law Center at the University of Washington. Meanwhile, the state has always tried to impose its will on Indian communities, and Congress has, over the years, authorized many of the incursions, he says. The Supreme Court, however, has “repeatedly recognized that tribes have aspects of sovereignty that have not been lost,” says Anderson.

But it’s primarily been up to the tribes to remind the state and federal governments about their special status, he says.

“We have to teach right here in this town,” says McCloud, referring to Washington, D.C. Administrations come and go, so it’s a never-ending educational mission. Now, he says, the Indian nations have to teach President Trump.

An agreement forged out of necessity

Hank Adams, an Assiniboine-Sioux and civil rights activist, writes in the exhibition catalog, Nation to Nation, that during the 1854 negotiations of Medicine Creek and the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott, Native Americans vigorously supported keeping their traditional hunting and fishing rights.

Anderson thinks that Stevens was not the originator of the rights idea, but that he was well aware the tribes would never agree to the treaty without being able to continue fishing and hunting on their traditional lands.

The tribes were paid a total of $32,500 for their land, about $895,000 in today’s dollars. Article 3 of the treaty states: “the right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations, is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary houses for the purpose of curing, together with the privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries, and pasturing their horses on open and unclaimed lands.”

They were not pushed off the land altogether, but were given several tiny parcels to live on: a small island called Klah-che-min (now known as Squaxin, on the southern reach of Puget Sound near present-day Olympia); 1,280 acres on Puget Sound, near the mouth of what was then called the She-nah-nam Creek (to the east of Olympia); and 1,280 acres on the south side of Commencement Bay, which is where the city of Tacoma is now.

The Nisqually tribe Chief Leschi reportedly refused to sign. Though his “x” is on the treaty, some historians and tribe members dispute its authenticity. By 1855, a war was raging between the local residents and the Nisqually, aided and abetted by Stevens. Leschi was eventually a casualty. Accused of murdering a U.S. soldier, he was hung in 1858. (Exoneration came 146 years later in 2004.)

Fish wars

Clashes over treaty rights came periodically over the ensuing decades.

By the mid-20th century, states, including Washington, began to claim that tribal members were depleting the fisheries. And they argued that Indians should be subjected to state licensing and bag limits, says Anderson. Even though “treaties are the paramount law of the land,” the states argue otherwise, he says.

Washington State did what it could to hamper and harass the Indians who attempted to fish anywhere outside their reservations. Nisqually member Billy Frank, Jr. became the leader of the resistance movement. In 1945, as a 14-year-old, he was arrested for the first time for fishing. By the 1960s, with the civil rights movement in full swing, Frank—who had been arrested some 50 times at that point—joined other minority groups in demanding full rights.

Thus began the “Fish Wars,” which pitted Native American activists—who wanted to exercise their treaty-given rights—against non-Indian anglers and the state, who believed that the Indians had an unfair advantage. Arrests were frequent, as were racist, anti-Indian actions.

It was often a raucous and rough scene. In the exhibition catalog Nation to Nation, Susan Hvalsoe Komori describes what it was like during the 1970s, when families attempted to fish on the Nisqually River, off the reservation. Washington State Department of Game officers “would come swaggering down with their Billy clubs, their macho holsters, and their lots-of-vehicles—they had boats, too—and they would go out, ‘get’ the Indians, and they would haul them back to their vehicles,” says Komori, who said that those arrested were often dragged by their hair and beaten.

The Department of Justice intervened in 1970, filing suit against the state of Washington to enforce the Medicine Creek Treaty. It did not go to trial until 1973. When the judge—George Boldt—issued the decision in United States v. Washington in 1974, it was a massive victory for the Washington tribes, but also for all Indian nations.

“It really made it very clear that the U.S. government was upholding the treaty rights of Native American people,” says Hirsch. It sent a message to non-Native people, and gave tribes notice that they could go to court—and that their rights would be affirmed, he says.

The state appealed, but the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Boldt decision in 1979.

Billy Frank, Jr. received numerous accolades for his work in asserting the treaty rights, including the Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism in 1992 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015.

Conservation and preservation—the next battleground

Frank, Jr. died in 2016, but his son, Nisqually tribal council member Willie Frank, III, who has long been active in the fishing rights battle, has taken up the fight.

Some in the state and some non-Indian fishermen continue to question the rights of the Nisqually. Contrary to perception, “it’s not our goal to catch every last fish,” says Frank, III. “I would rather stay off the river and bring our habitat back than fish every last fish.”

In January, the tribe did just that—they decided not to fish for chum salmon during the usual season. It was the first time anyone could remember in the Nisqually history that chum fishing had not occurred, says Frank, III.

The Nisqually and some 19 other western Washington tribes co-manage the Puget Sound salmon fisheries with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife—a result of the 1974 decision. The arrangement has mostly worked, but bumps are not uncommon, says Frank, III.

In early 2016, the co-managers were struggling to come to an agreement on catch limits before the season started—in the face of forecasts of a vastly depleted stock due to loss of habitat, problems at hatcheries and pollution. A federal waiver allowed the tribes to do some ceremonial fishing—essentially just taking a small catch in concordance with the treaty rights—but that rankled many non-Indians. According to a report in Indian Country Today, about 20 protesters—waving signs that said “Fair Fisheries for Washington,” and “Pull the Nets,” among other slogans—gathered on a bridge over the Skagit River while members of the Swinomish tribe—one of the co-managers of the fisheries—used gill nets to catch salmon.

“It got kind of ugly last year,” says Frank III, who believes that some of the anger at tribal anglers would be lessened with better knowledge of treaty rights.

The tension between Washington State and tribal nations over treaty rights is ramping up again. In May, a panel of judges on the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a lower court’s decision that Washington must fix some 800 culverts that carry streams beneath state roads that tribes say are interfering with the salmon habitat.

The state has been, and will likely continue fighting the decision, and not just because of the expense—an estimated $2 billion—says Anderson. Officials “don’t want the treaty rights dictating their conservation policy,” he says.

But Frank, III says, “We’re saying as co-managers you need to be responsible”—and that means practicing environmental stewardship.

For the tribes, it’s not about making money from fishing. “You can’t anymore,” he says. “It’s more about being out on the water—getting out and enjoying ourselves. As long as we’re getting our nets in the water and teaching our youth,” says Frank, III.

McCloud, the Nisqually chairman, believes that perhaps everyone needs to stop fishing for a year or two to allow the fish stocks to recover. “That’s important for our future—that’s our way of life, spiritually, culturally. That’s what our ancestors did,” he says.

And he doesn’t think it’s too much to ask. “We’re not a greedy race. We try to stick with what we know,” says McCloud.

"Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations," on view at the National Museum of the American Indian, has been extended through 2021.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)