Steven Young Lee Crafts Perfectly Imperfect Pottery

Rigorously trained, this artist makes works that look woefully broken

When artist Steven Young Lee shows one of his peculiar works to those unfamiliar with his “deconstructive” approach to pottery, it sometimes requires an explanation.

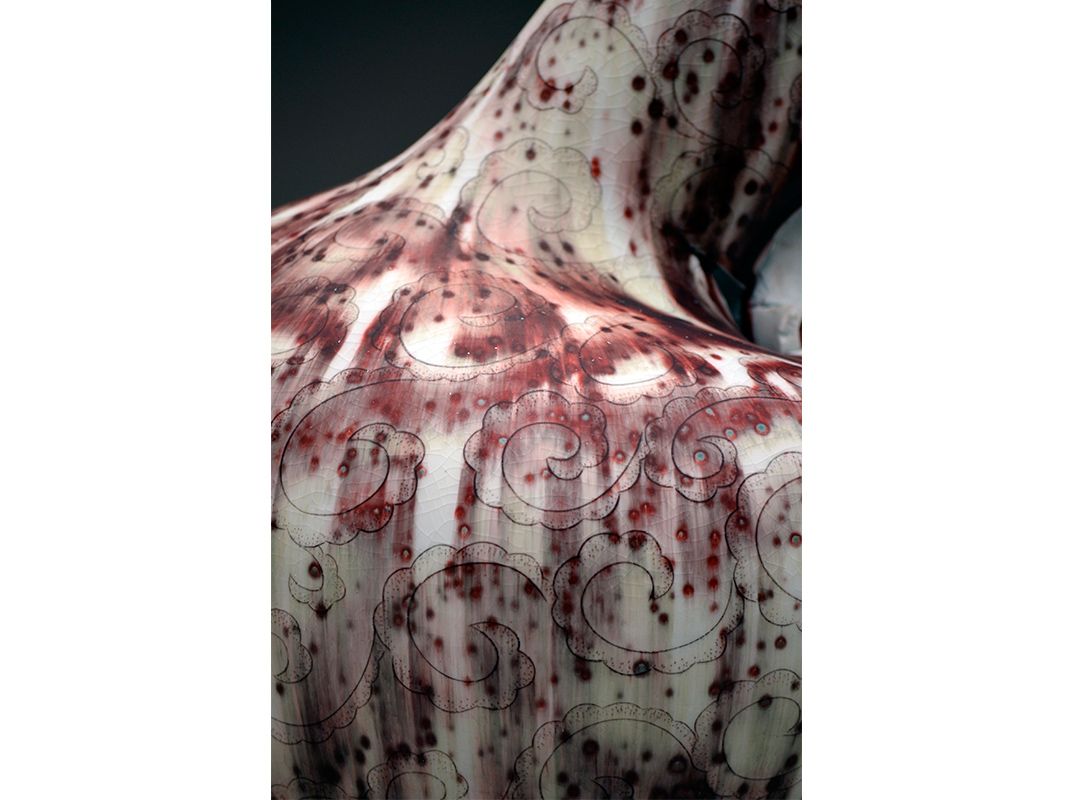

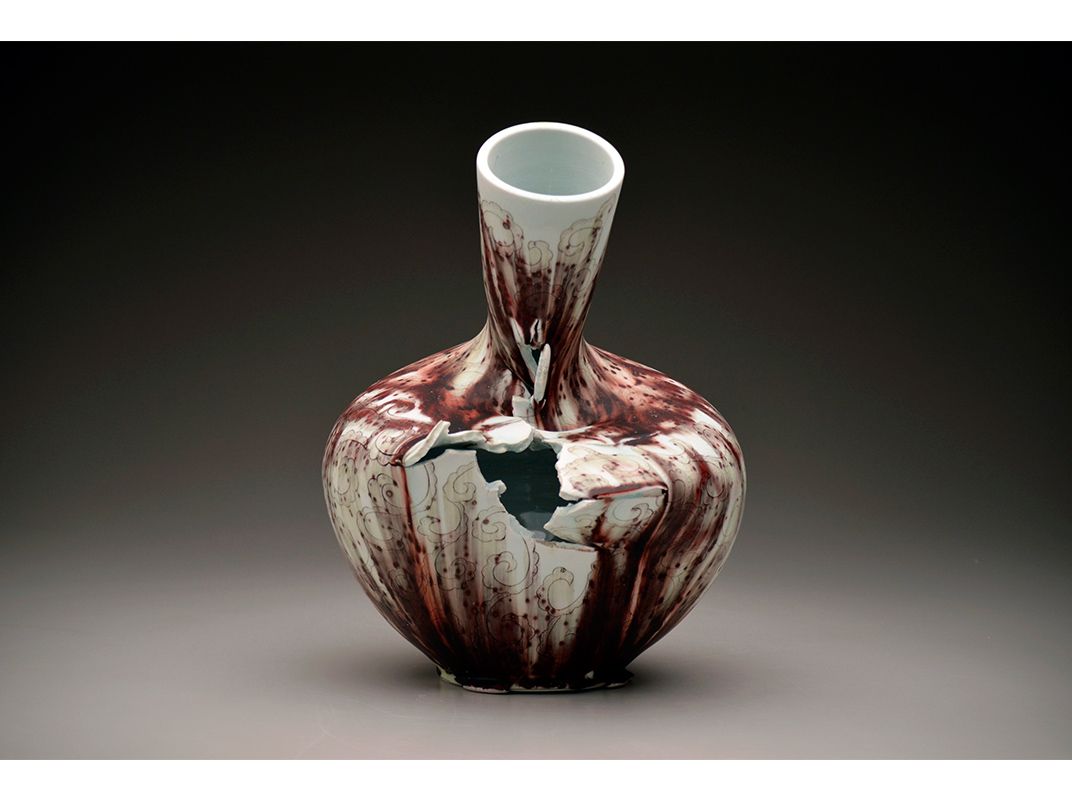

“I have to explain to them, ‘No, I meant to do this,’” says Lee, referring to the cracks or wide fissures that mark his vessels. His artwork Peonies Vase looks torn open while the surface of his Vase with Scroll Pattern looks as if a hand has been punched through it. “That’s part of what’s interesting to me: Trying to use the material in a way that most people in ceramics are trying to avoid.”

While ceramics is an artistic field associated with perfection and symmetry, Lee, whose work is on view as part of the 2016 Renwick Invitational, Visions and Revisions, is interested in exploring “clear failures” and the viewer’s response to it.

“People have visceral reactions to it—but if you meant to do that, it changes the value versus if you didn’t mean to do it,” he says. “In craft-based mediums, mastery of materials or your ability to execute it has an impact on how people create value. If it was happenstance, it changes how people perceive the work.”

Contemporary imagery also comes into play in his works, such as the 2010 Another Time and Place, which features a Chinese landscape with dinosaurs roaming about. In his 2008 Granary Jar, a traditional Japanese landscape of pine trees shares space with the cereal-box characters Toucan Sam and Count Chocula.

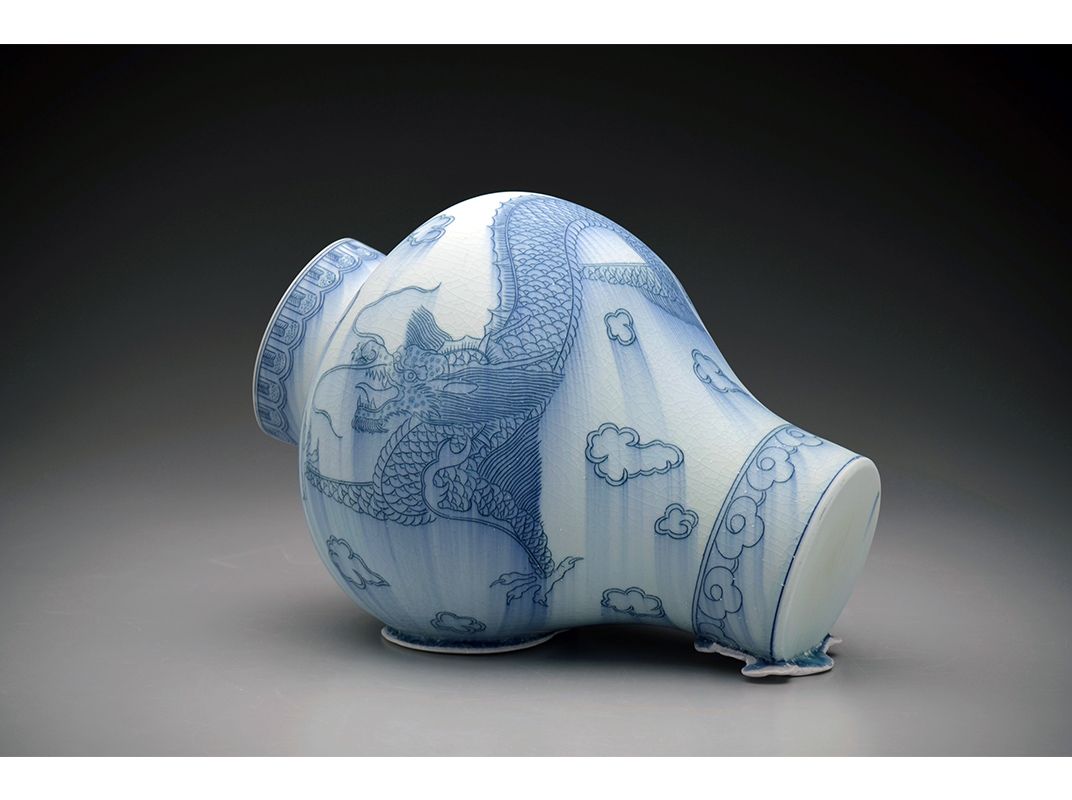

Lee’s exploration of failure grew out of his early studies, which immersed him in functional pottery at New York’s College of Ceramics at Alfred University, as he spent his time trying to avoid these mistakes. His 2009 Landscaped Jar lost its foot and ended up on its side during firing, but Lee was pleased with the result.

“I’d create a crack and assume certain things would happen, but much different things would happen,” says Lee. “It became a process of letting go of expectation.”

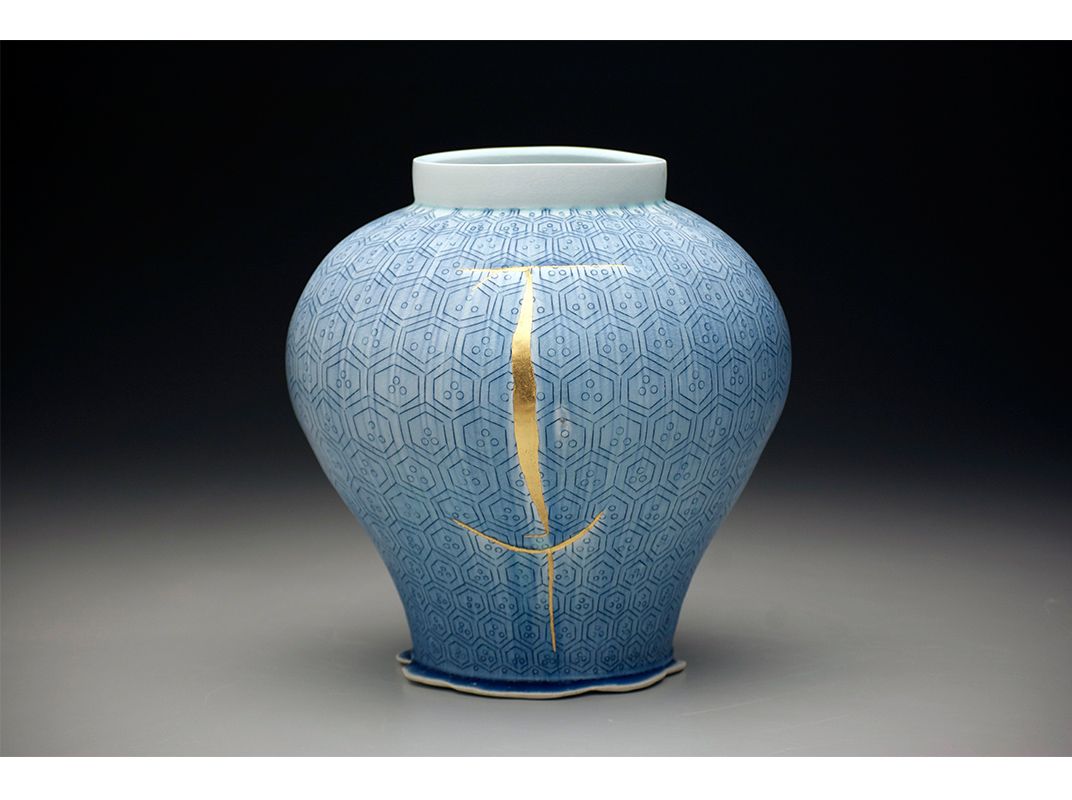

While his art upends traditional expectations of ceramics, the centuries-old history of porcelain fascinates Lee and informs his sculptures. He has studied the rise and decline of porcelain manufacturing, as well as its distribution throughout the world, as it originated in China and was then imitated in Europe and elsewhere. This knowledge informs themes in his work, such as comparing mass-produced to handmade pieces, or perfect versus flawed.

“One of the things that I think is simplest is using something that is so recognizable and familiar as a ceramic vessel or pottery form,” he says. “These are things that people universally understand or know what it represents,” which provides him with fertile artistic soil in which to work.

Lee traveled to Jingdezhen, China—the reputed birthplace of porcelain—in 2004 for a fellowship at the Sanbao Ceramic Art Institute, learning of the rigorous training and pursuit of perfection (and distaste for innovation) expected of the potters there. He also traveled to South Korea, where the tradition is based more in utility than refinement. Lee would later draw inspiration from Asia, with materials such as blue and white ceramics. He was drawn to the buncheong ware tradition of Korea, which uses copper inlay and white slip glazing, and would later incorporate this into his own sculptures.

This deeper appreciation of pottery informed Lee’s work from this point on, as he began creating his Spirit Vessels series, including the 2007 In the Name of Tradition, a porcelain vessel featuring butterflies atop brick beehive kilns, meant to resemble those used at the Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts in Helena, Montana (where he began working in 2007, and today serves as resident artist director).

The “perfection” that pervades ceramics, which Lee suspects grew partly out of the industrial production of ceramics and the standard of acceptability, is both his muse and his point of departure. He infuses his works with references both ancient and modern, looking at different forms across different cultures, whether European or Asian. And he explores how form can travel from one part of the world to another, having studied objects in museums and reference books, extracting different patterns, motifs, forms, and glazes, pulling them together to create a kind of collage.

“A lot of it is cutting and pasting reference points,” says Lee.

Seeing such an extensive collection of his work gathered in one room has been a particular treat for Lee of the show at the Renwick Gallery.

“It doesn’t feel like I’ve been making it that long,” he says. “It feels that I’m at the beginning of a long journey.”

"Visions and Revisions: Renwick Invitational 2016" is on view on the first floor of the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Renwick Gallery through January 8, 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)