The Storied History of Giving in America

Throughout American history, philanthropy has involved the offering of time, money and moral concern to benefit others, but it carries a complicated legacy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06/98/0698fec4-7287-4b3f-b6a2-68feb7e1f711/gettyimages-1224827407.jpg)

People moved quickly to the water’s edge that September day in 1794. A boy, around eight years old, was in the ocean and in distress. Alerted to the crisis by a young child, old Captain Churchill called out for help. A few people came running, but the tide was rising and the boy slipped beneath the water’s surface—until, all of a sudden, he rose again. Immediately, one of the bystanders, Dolphin Garler, an African American man who worked in a nearby store, dove into the water and pulled the child out. Although worse for the wear when he was pulled out, the youngster survived and was given over to his panicked mother.

The Plymouth, Massachusetts, incident would spark a townwide philanthropic effort to recognize Garler for his bravery. Four townsmen lobbied a statewide lifesaving charity, writing up an account of the rescue and before long Garler was awarded a sizeable award of $10 from the Humane Society of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, an organization established in 1786 to promote the rescue and resuscitation of victims of drowning and other near-death circumstances. It was the organization’s single largest award given that year.

Like other humane societies in Europe, the Caribbean and North America, the Massachusetts group disseminated information on resuscitation techniques and rewarded rescuers whose actions were verified by respectable and well-to-do men. At a time when white Americans assumed that free blacks were a threat to the health of the republic, the charities were giving rewards to black rescuers and for rescuing black drowning victims at the same rate as they did to and for white people. An outgrowth of the humane society supporters’ commitment to an expansive moral responsibility in a maritime world, this approach reflected the humane society movement’s commitment to aiding people regardless of background.

Beyond tangible rewards, in an era when many believed that acts of benevolence were evidence of civic responsibility, this attention from prominent charities representing the nation’s elite given to Garler and other African Americans signaled that they were worthy members of society in the new republic. The recognition of African Americans by the Humane Societies highlights how philanthropy—at an optimistic moment in the early United States—contributed to conversations about inclusion.

Today, philanthropy often refers to large financial gifts, typically given by very wealthy people, but throughout American history philanthropy has involved giving time, money and moral concern to benefit others. At the National Museum of American History, scholars and curators from the Smithsonian’s Philanthropy Initiative are exploring the topic of giving and its culture in American life by collecting and displaying objects, conducting research, including oral histories with notable people in philanthropy and hosting programs.

To encompass the breadth and diversity of giving in American history, philanthropy can best be defined as “recognizing and supporting the humanity of others.” Studying its history offers a lens for looking at how people have cared for one another and in what sort of society they have aspired to live. Objects in the Smithsonian’s collection show that Americans practicing the act of giving have tackled prejudice and racism, economic disparities, and the human suffering they cause—sometimes tentatively, and sometimes head-on.

On the flip side, the history of philanthropy also reveals how the practice can reflect and reinforce inequity. The work done by the Initiative requires being sensitive to the inspiring, complex and at times divergent perspectives of people throughout the charitable ecosystem—donors, leaders, staff, recipients and critics. The history of this diverse, empowering American tradition belongs to all of them.

Like the well-off white men in the humane society movement, a group of African American women in the mid-1800s also turned to philanthropy to pursue equality—their own, in this case. It began with another dramatic rescue. This time, the rescuers were white, the endangered people were black, and fire, not water, threatened lives.

The year was 1849, and the trouble started in an all-too-familiar pattern when a crowd of white men and boys attacked an African American neighborhood in Philadelphia. In the 1830s and 40s, white rioters periodically terrified black Philadelphians by assaulting them, destroying their property, and setting fires. A group of white volunteer firefighters crossed racial lines to help and give aid to the endangered black neighborhood. The firefighters were under no legal obligations to help, but did so at their own peril.

To honor the firefighters, a group of black women presented the group with a handsomely embossed silver trumpet, now held in the the Smithsonian collections. It bears a lengthy but powerful inscription, which in its distilled form, certainly resonates with today’s Black Lives Matter movement.

Presented to the Good Will Engine Co.

By the Colored women of Philad.a

as a token of their appreciation of their manly

heroic, and philanthropic efforts displayed

upon various trying occasions in defence

of the persons’ rights and property of

their oppressed fellow citizens.

The women chose words for the inscription that both praised the firefighters and asserted their community’s own humanity. The word “philanthropic” in that era meant “love of humanity.” By calling the men “philanthropic” for aiding black Philadelphians, the women were underscoring the inclusion of African Americans in the circle of humanity.

Everyday philanthropy also sustained Americans whose grueling labor fashioned the fine goods that wealthier countrymen would collect for their estates and in turn, deem worthy of being donated the Smithsonian.

Silver-mining, for instance, was perilous work. “Scalding water, plummeting cage elevators, cave-ins, fiery explosions, toxic air,” incapacitated miners, widowed their wives, and orphaned their children, writes historian and material culture scholar Sarah Weicksel in her examination of Nevada silver-mining communities in the late 1800s. Women in mining towns such as Virginia City and Gold Hill led the way in creating charitable institutions and raising the funds to care for those in need.

The winter of 1870 saw the Ladies’ Mite Society of Gold Hill organizing a “Grand Entertainment . . . Expressly for Children” with games, dancing, refreshments and more to help fill the group’s coffers. The special event not only provided fun for the children, but also included them in the community of philanthropy, imparting a lesson on its value. Families’ support for the event, joined with the contributions of many miners’ families, enabled the Ladies’ Mite Society and the Catholic Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul to meet local needs.

These women of Philadelphia and Nevada lived in a world where women’s involvement in philanthropy was familiar; that hadn’t always been the case. In the 1790s and early 1800s, women in the United States were new to organized benevolence. Although they faced some initial skepticism and even outright opposition from some quarters for violating gender norms with their organizational leadership, women carved out public roles caring for other women and children, supporting missionary efforts, and, in time, advancing a range of causes.

By the late 1800s, not only was philanthropy a widely accepted way for women to influence public life, it also led some Americans to embrace the idea that women should also have the right to vote. For Emily Bissell, however, the possibility of suffrage threatened the power she saw women exercising through philanthropy. Her lifelong career of social activism began in the 1880s when she was troubled about the limited recreational opportunities for working-class young men in her hometown of Wilmington, Delaware. Industrialization was changing the city and not for the better for working people. Skilled jobs were disappearing, and neighborhoods were becoming crowded. As Bissell and other middle-class residents saw it, with little to do, young men fought, loitered about, and generally behaved rowdily.

Only in her early 20s, Bissell led the creation of an athletic club based on a top-down approach common among many white well-to-do reformers in this era. Along with sports and exercise facilities, the club included a reading room, heavy on religious literature, for neighborhood boys and young men. In time, it expanded its programs to serve girls too. Launching the athletic club also launched her philanthropic career that would, in time, involve creating the powerhouse Christmas Seals fundraising effort to fight tuberculosis, advocating in favor of child labor laws, and more. The success of women activists came from being, as Bissell saw it, apolitical. Women's civic inequality and inability to vote, she believed, enhanced women’s philanthropic clout. In her view, having the vote would threaten their influential role.

If Bissell saw disenfranchisement help shape the nation through philanthropy, Mexican American physician Hector P. Garcia viewed his giving as an opportunity to confront the hardship and discrimination his community faced in south Texas and the United States during the mid-1900s. “[T[hey had no money, they had no insurance” is how Garcia’s daughter, Cecilia Garcia Akers, remembered many of her father’s patients. They were also discriminated against.

Schools were segregated. Military cemeteries were, too, in spite of a strong tradition of service among Mexican Americans. Garcia himself knew discrimination firsthand. Because of racist admissions restrictions, he was the only student of Mexican origin in his medical school, and no Texas hospital would take him for his residency. At the start of World War II, Garcia was not yet a citizen when he enlisted in the Army, seeking to serve in the medical corps despite his commanders’ doubts that he was even a doctor. His experience spurred him to fight for Mexican-American veterans’ and civil rights by establishing the American GI Forum, a group to advocate for Latino veterans, as historian Laura Oviedo has explored in the larger context of Latino communities’ philanthropy.

Some white residents, Garcia’s daughter remembered, opposed his activism. After moving his family to a white community, neighbors routinely pelted their home with eggs, spit on the children and harassed them in other ways. Besides his activism, Garcia sustained his community by providing free medical care to thousands of impoverished patients.

A few decades later and thousands of miles away, a group of young activists in New York’s Chinatown also understood the connections between access to health care and equal citizenship. In the 1970s, Chinatown residents faced a range of barriers to medical care, as Weicksel writes, including language gaps and prejudice. Few health care providers spoke Chinese languages and many residents didn’t speak English. At city hospitals, Chinese Americans experienced dismissive treatment. Inspired by the free clinic movement then burgeoning in California, and by the civil rights movement, Asian American activists Regina Lee, Marie Lam, Tom Tam, and others aligned with the cause volunteered to organize health fairs to survey community needs.

Without fully understanding what they were getting into, as Lee remembered, they next established a basement health clinic. Funds were so tight that one of the doctors built a homemade centrifuge for testing blood. That was then. Nearly 50 years later, the small basement clinic is now a federally qualified community health center with multiple locations in New York City and a leader in providing culturally appropriate health care to underserved communities.

Before they could reach such great heights, however, the young activists first needed the community to recognize the vastness of the problem at hand. Tulsa, Oklahoma, teacher Teresa Danks Roark likewise sought with her philanthropic engagement to gain recognition for a community challenge.

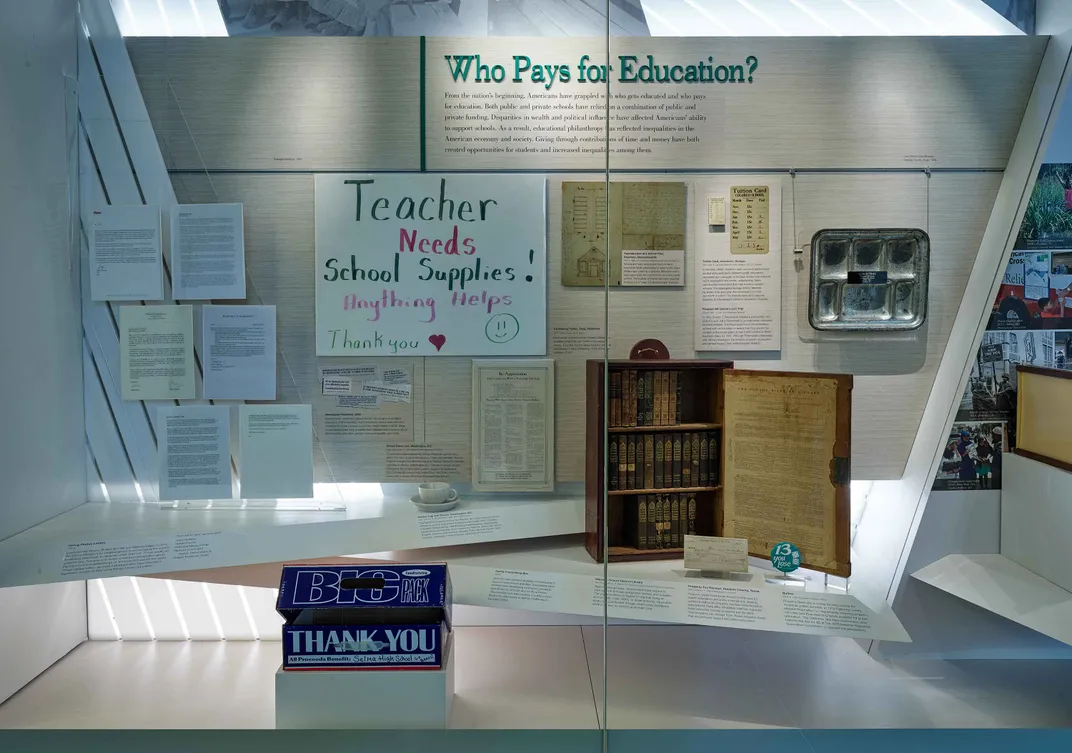

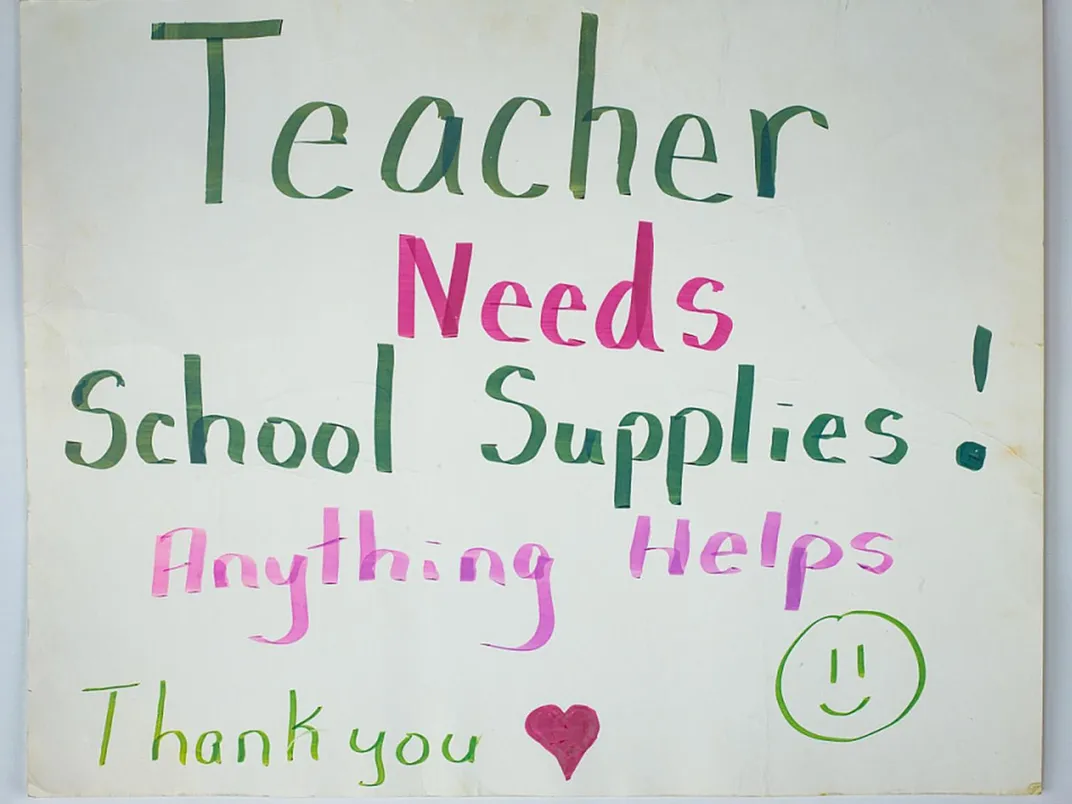

A cut in school funding led Roark to take to panhandling. Most public school teachers use some of their own funds each year to buy school supplies, and many use online platforms (such as Donors Choose) to solicit donations from family, friends and concerned strangers. (During the Covid-19 pandemic, some educators have also raised funds for personal protective equipment for classroom teaching.)

In July 2017, Roark was fed up with having to struggle for adequate school supplies and, spurred by a joking suggestion from her husband, stood out on the street with a homemade sign asking for donations. A photo of her roadside fundraising went viral and contributed to an ongoing national debate about who pays for education and who sets educational priorities. Raising much more money than she had sought, Roark and her husband set up an educational nonprofit, Begging for Education, and have been learning the ins and outs of making change through philanthropy. Roark’s poster, meanwhile, is now in the Smithsonian’s collections.

Like Roark, everyday philanthropists from the early republic to today have recognized that pursuing the country’s promise was not just the work of formal politics. Engaged philanthropy is vital to democracy. The museum’s collections reveal that many Americans, whether they’re prominent or unsung, know this well.

The online exhibition "Giving In America" at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History is complemented by the museum's Philanthropy Initiative.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ABM_head_shot.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ABM_head_shot.jpg)