The Story Behind Those Jaw-Dropping Photos of the Collections at the Natural History Museum

The images capture only a fraction of the millions of creatures and objects that are stored away from the public eye

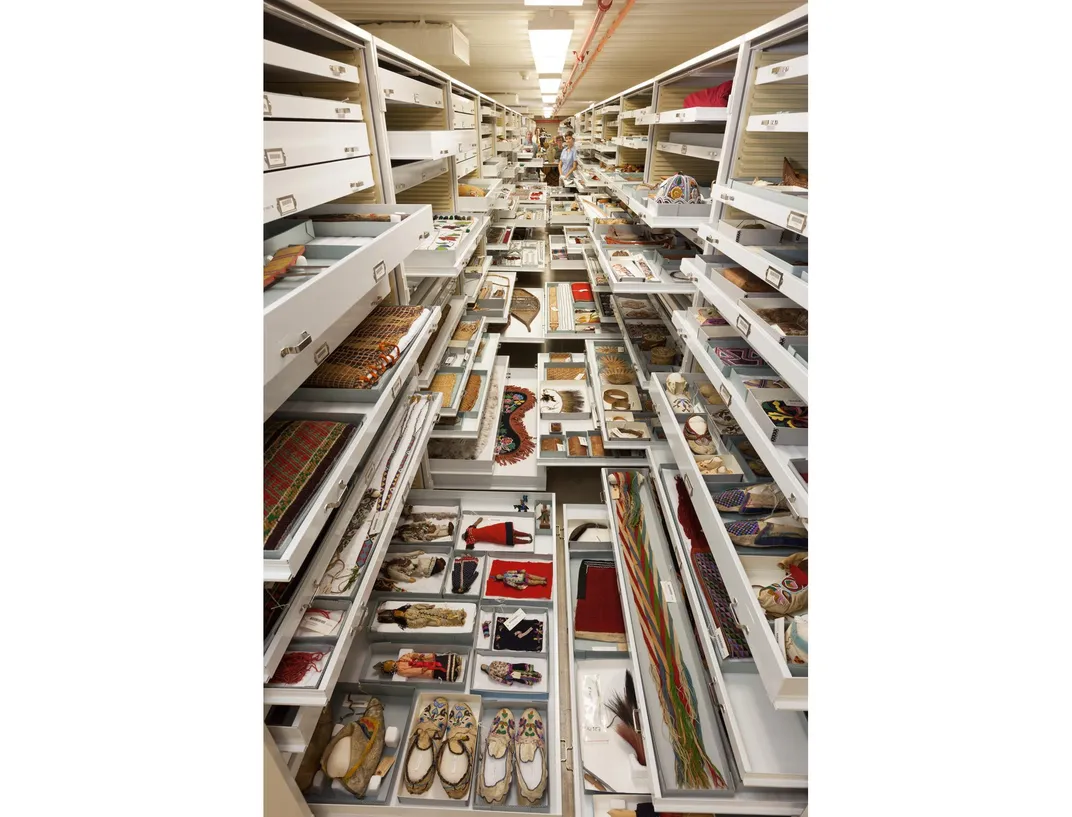

Wandering the warren of collections facilities and scientific laboratories that the public rarely sees at the National Museum of Natural History is like peeking into a reconstruction of Noah’s Ark. Filling every drawer, cabinet and shelf in sight are millions of taxidermic birds and mammals, preserved worms and fishes, skeletons and fossils, and so much more.

Seen all at once, the assemblages of creatures and objects make for a brilliant visual image. It's no surprise, then, that photographs of the museum's collections, one of the largest in the world went viral on Reddit and elsewhere. Every few years, it seems, someone else discovers the photos captured by the museum's acclaimed photographer Chip Clark, and they are seen anew by hundreds of thousands of people. The images highlight the diversity of samples as well as some of the researchers, field scientists and specialists that work with it.

The Natural History museum's collections are so large that despite the sprawling three levels of the building open to the public, less than one percent of them are on display at any given time, says Carol Butler, the assistant director of the museum’s collections. But they do form the wellspring of the scientific research that informs the exhibitions on view.

“[Clark] thought the collections were fabulous and he wanted to show the inner life of the museum and the richness of the collections,” says Butler.

The earliest photo is of the striking avians. The diversity and brilliant color of birds makes them a natural choice for that first image, Butler explains. “It’s a famous image within the Smithsonian and some science museums because it encapsulates so much information about museums and collections.”

The remaining images were staged and created over the course of nearly 20 years, says Kristen Quarles, digital collections specialist at the museum. Before his passing in 2010, Clark orchestrated the last few images of the set for use in the museum’s centennial celebration.

We talked with Butler to get more information about the pictures and the importance of the museum's collections.

How long did it take to create these pictures and what was involved in the process?

There’s one image of the bird collection. And what I remember [Clark] told me was that it took about eight hours to set up that shot. The collections are stored taxonomically according to the tree of life. But to get beautiful colors and good artistic composition, they had to move some drawers to different positions.

It took an artistic eye, a lot of patience, and probably a certain amount of flexibility to shimmy under drawers or to move sideways past pulled-out drawers. It also took an understanding of what science needed to be expressed through the photographs.

So they’re beautiful but they're also an example of museum practice, collections management and science. I think that's why they appeal to so many people.

Museums are an important resource for many scientific studies, but the public doesn’t often get to see this side of the collections. Could you tell us a little bit about how these collections are used?

Museums document what we observe about the natural world and how our connectedness with it changes through time. So in a sense, portions of the collection are a snapshot of what was living in a certain place at a certain time.

They can help us reconstruct the environment, the ecosystem, look at how animals and plants interacted and help us think about how the climate influenced the existing plants and animals.

Just as we wouldn't want to say one human being represents all of humanity, one bird doesn’t represent all of the birds of a certain species. We need lots of individual birds because part of what we are looking at in understanding a species is its’ variability.

[The collections allow] you to ask detailed questions, ask broad questions, ask comparative questions—and it’s that good science that museums are here to support.

After the specimens are each studied and documented, why is it valuable to keep them?

The specimens are like the raw data [of a study]. If we don't keep the raw data, we can't go back and validate an interpretation or a result. An essential element of good science is to be able to reproduce a finding, an interpretation or a result.

We also use them in new ways over time. Who knew in the 1930s that you can do molecular work with collections? Who knew that we would develop the kinds of imaging and chemical analyses that we can do now? As technology changes, old collections get new uses.

What are some other reasons for keeping so many samples from each site?

You could look at our invertebrate collection—animals without backbones—and you could ask: Why do you have so many of these worms or these crustacea from the Gulf of Mexico?

In part because if they were collected at different points in time, we can learn something about how the environment is changing in the Gulf of Mexico. That information became particularly important after the Deep Horizon oil spill that occurred a couple of years ago.

So if you look at the picture and just see a whole bunch of jars of crustacea, you [are missing part of the story]. Behind every one of those specimen is a lot of data and a lot of very careful record keeping.

An old collection might [alternatively] be from a place that no longer exists. Think about islands that are at close to sea level in the Pacific. When the island goes away, [the museum’s specimen] could be the only representation we have of the biodiversity or the geology of that island. And the world is changing all around us, very rapidly.

What we have in museum collections are sometimes the only ones, like specimens of extinct species—the passenger pigeon, the dodo.

With such extensive collections, how much work goes into upkeep and maintenance?

Taking care of collections is an ongoing activity and at the Smithsonian. I am thankful that we have both trust funds and federal funds that help us with this.

Going into the field is expensive, so taking care of what we have is a wise and prudent move. And that begins with a good building that has a sound structure and doesn't let in water, wind, pests, dirt or particulates in the air. It’s also important to have a good container and [for some specimen] the appropriate preserving liquid.

So it's environment, it's building, it's appropriate containers. It's maintaining temperature and relative humidity and light control. Everything is in a process of decay, even rocks. And what we are trying to do is slow that down.

Scientists travel from all over to work with your specimen, does that affect preservation?

We are very careful and we're always trying to find the right balance between preservation and supporting access and use because the collections need to be used. But each time you use something, you hasten its deterioration. So we use careful handling practices, we use good environments, and we try to use the best preservation methods available.

Was the museum impacted by the National Science Foundation’s recent announcement that they are suspending funding for the Collections in Support of Biological Research?

We were not directly impacted because we are not eligible for National Science Foundation funds from that program. But caring for collections doesn't just happen at this museum—it happens at museums and collections across the country, and many organizations are probably going to be impacted by it.

If funding decreases at a university, for whatever reason, then a collection may become what we call orphaned. As a community of museums, we try to make sure that collections aren't lost to science and public education and enjoyment. Sometimes these orphans become incorporated into the collection of a different organization or museum. We all band together informally to try to make sure that collections are kept safe, secure, preserved and accessible for use.

For anyone interested in working with museum collections, what kind of degree do you need?

It's helpful to have a degree in science—biology, anthropology, geology, paleontology. But there are also ways that people can get training in a museum studies program to learn about collections management and other skills we use like creating databases or taking and processing images.

There are many ways to get a museum job, and to do the kind of work that some of the people in the images do.

Do you have any other thoughts to add about the images?

These images come from a motivation to show people, in a beautiful and interesting way, a view into the richness of the collections. These are America's collections—so we want to give people a view into the collections even though we can't invite every single person to walk through the storage areas.

We want people to see how cool it is and hopefully be inspired.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/e7/81e7e394-6c2b-49ec-80bd-44a59c019557/birds_staff_lg.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Wei-Haas_Maya_Headshot-v2.png)