The Story of Brownie Wise, the Ingenious Marketer Behind the Tupperware Party

Earl Tupper invented the container’s seal, but it was a savvy, convention-defying entrepreneur who got the product line into the homes of housewives

:focal(594x182:595x183)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/00/b30099b4-ef17-4069-b89d-bbe8f4d489ef/tupperware-party.jpg)

Today, Earl Tupper and Brownie Wise are remembered for their acrimonious split, but neither of the two entrepreneurs of 1950s America would have been able to create Tupperware alone.

Together, the inventor and saleswoman made Tupperware a household name—and there’s nowhere their shared legacy is more visible than the Wonder Bowl.

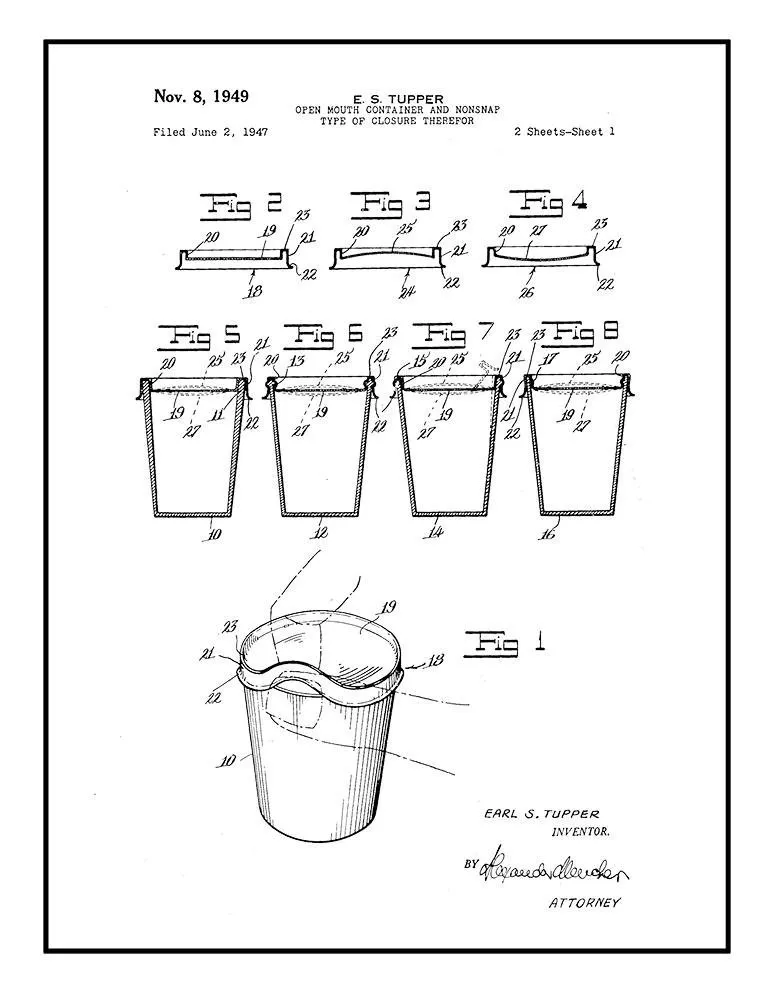

The Wonder Bowl has always been “the linchpin of Tupperware,” says Smithsonian curator Shelley Nickles, who frequently works with the National Museum of American History’s extensive Tupperware collection, which includes more than 100 pieces made between 1946 and 1999. The bowl was translucent like milk glass but more durable than any container before it. It was air- and water-tight as well, thanks to Tupper’s double sealed lid, patented in 1947, but could be sealed and unsealed just by pressing. As Tupperware dealers would tout to their clients a few years later, it was perfect for the fridge or for outside entertaining.

In the years following World War II, plastics inventor Tupper designed novel products intended—unlike most plastics to date—for the consumer market. Before this, plastic goods were manufactured for use in the war as everything from insulation for wiring to truck parts, but not for home use. Tupper created a new kind of plastic from oily polyethylene slag: called “Poly-T,” it was easy to mass-produce in a myriad of colors and form in a mold, giving it the clean modern look that set the Wonder Bowl apart.

When it was first released in 1946, the bowl—Tupperware’s very first product—was widely praised by the burgeoning plastic industry, says Nickles, which wanted quality plastic products in consumer hands. “It was also featured as an icon of modern design,” she says. An article in House Beautiful described its sleek, translucent, green-and-white lines as “fine art for 39 cents.” That was the original cost of the bowl, which translates to about $5.50 in today’s money. Now, a three-piece set of the Wonderlier bowl, its successor, goes for $35.00. Elsewhere, Tupperware products were described as “featherweight,” “pliable” and “modern.”

But even though the Wonder Bowl earned design and industry accolades, it wasn’t selling in department stores, and neither were Tupperware’s other products. They were too different: plastic was an unfamiliar material in the home. The patented Tupper seal had to be “burped” before it would work: it was difficult for people accustomed to glass jars and ceramic containers to intuit how to use the seal.

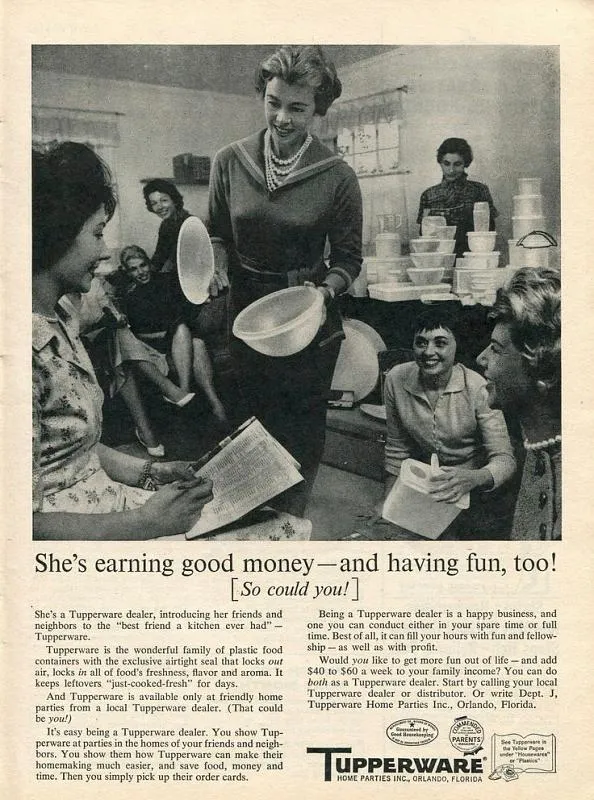

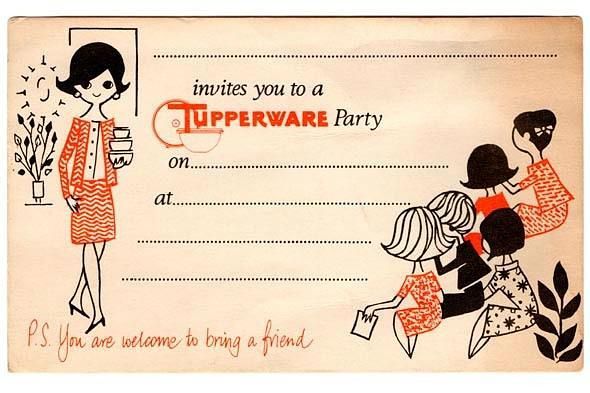

Wise, a former advice columnist and a secretary who lived with her mother, Rose Humphrey, and her young son Jerry Wise in Miami, Florida, however, saw potential. She started her own Tupperware-selling business, Patio Parties, in the late 1940s and recruited women to sell for her. The sales strategy was rooted in the home selling model pioneered by companies like Stanley Home Products, which used home sellers to demonstrate novel products, but Wise put women front and center as sellers at parties, then known as “Poly-T parties.” Instead of just a product demonstration, a Tupperware party was a party, whose hostess was supported by a Tupperware dealer—an honored guest who could demonstrate the products and sell. Hostesses received merchandise as a thank-you for providing their homes and social networks. By 1949, Wonder Bowls were flying out of the hands of Wise’s sellers: one woman sold more than 56 bowls in a week.

At this point, however, Tupper himself was just catching on to the idea of home selling. “In 1949, Tupper published a mail-order catalogue illustrated with product settings in his own New England home and featuring a range of 22 standard Tupperware items,” writes historian Alison J. Clarke in Tupperware: The Promise of Plastic in 1950s America. The products came in delicious-sounding fruit colors like raspberry and orange or expensive-sounding gem tones like sapphire and frosted crystal. But despite these appealing images—and the fact that unbreakable, sealable, leak-proof Tupperware was several steps above what people were using at the time to keep food in the fridge—consumers weren’t buying it. Tupperware was too high-tech and unusual to appeal to shoppers who weren’t used to having plastics in the home.

Wise’s innovation lay in figuring out how to make a plastic bowl familiar. The life of this divorced breadwinner was different from those of the married suburban housewives who Tupper was targeting, but she understood that they could be both the ideal market and the ideal salespeople for this new dishware, and she was able to create a Tupperware empire.

In 1951, Tupper hired Wise as his vice president of marketing, an unprecedented position for a woman, says Bob Kealing, author of Life of the Party: The Remarkable Story of How Brownie Wise Built, and Lost, a Tupperware Party Empire. She took charge of the newly created division of the company centered around what Kealing calls “the home party plan.” At the iconic Tupperware party, a well-dressed dealer with practiced demonstration skills would show the hostess and her friends how to use this high-tech, colorful new kitchenware. She’d lead the group in dramatic party games, like tossing a sealed Wonder Bowl full of grape juice around the room to demonstrate the strength of its seal. Dealers had the support of the Tupperware company and their regional dealer network, who would manage and encourage them to develop their demonstration skills. In return, they were able to earn income and recognition: they sold products at retail prices, but Tupperware only took the wholesale price of an item. Husbands, as the titular holder of the family money, often stepped in to deal with distribution, Kealing says, but the selling belonged to the dealers.

At Patio Parties, Wise had motivated her dealers by asking them to share their successes and expertise with one another. She ran a weekly newsletter for them and touted the idea of positive thinking, making Tupperware-selling as much a lifestyle as a job and empowering women who didn’t get recognition for doing household chores or caring for children. “She really could speak to her dealers’ dreams,” Kealing says. She listened to the women who worked for her and made marketing decisions based on their feedback. The saying she was known for: “You build the people and they’ll build the business.”

In the 1950s, as Tupperware sales soared, hitting $25 million in 1954 (more than $230 million in 2018’s money), products like the Wonder Bowl, Ice-Tup popsicle molds and the Party Susan divided serving tray came to represent a new post-war lifestyle that revolved around at-home entertaining and, yes, patio parties. More and more women (and some men) became dealers and distributors, and not just white suburbanites. In 1954, there were 20,000 people in the network of dealers, distributors and managers, according to Kealing. Technically, none of these people were employees of Tupperware: they were private contractors who collectively acted as the infrastructure between the company and the consumer.

Tupperware’s marketing model relies on social networks, Nickles says, which means it’s highly adaptable to a specific dealer’s social circle and needs. That meant dealers included rural women, urban women, black and white women. A lot of these women were attracted not just by the opportunity to make money, writes Clarke, but for the self-help rhetoric Wise used to work with dealers. She held pep rallies for her sales force and an annual retreat where the country’s top sellers received awards and gifts. The network of dealers and distributors also acted as a support network for those within it, Kealing says. If someone in the network needed help to succeed, such as someone to pick up their merchandise, the culture of the network meant they could ask.

In these years, Wise became the public face of Tupperware, appearing in women’s magazines and business publications to tout Tupperware and the business culture she created. Tupper himself didn’t like making public appearances, so Wise stood solo in the limelight. Among other press appearances, she became the first woman to appear on the cover of Business Week. Tupperware in this period has been compared to a religion, with Wise its chief priest. She even carried a black chunk of polyethylene known as Poly around to sales rallies. Wise maintained that it was the original polyethylene slag that Tupper had gotten to begin his experiments with, and encouraged dealers to rub Poly, “wish, and work like the devil, then they’re bound to succeed,” writes Clarke.

Although she was a prominent figure, Wise was also a woman in business at a time when “she really didn’t have any [female] contemporaries,” Kealing says. She had to make up her own way of doing things, without peers or mentors, and she made mistakes along the way. She may also have been overconfident in handling Tupper, he says, believing her own great press and not making him feel valued for continued innovation on the product side, he says. As time went on, she and Tupper fought frequently over company strategy and management. By the late 1950s, Tupper was looking to sell the company, and “his gut told him it would be less attractive to sell with an outspoken woman at the helm of the sales end,” he says. In January 1958, he and the board of directors fired Wise, who did not have a formal contract. After taking them to court, Wise received a one-time payout of a year’s salary, which was around $30,000. She went on to found and work at cosmetics companies that used the same kind of home party techniques, but none of them did all that well. Tupper sold the company in early 1958.

The modern Tupperware company has since worked to recognize Wise, donating $200,000 to an Orlando park near the company’s headquarters in 2016, so it could be renamed Brownie Wise Park, and adding her to the company’s official history. Her larger legacy, of course, is in creating the model for a whole field of home party businesses, from Mary Kay onwards. The home party model she pioneered at Tupperware has ensured the company’s continued success: it now does most of its sales abroad. But it’s also the basis for a burgeoning field of “side hustle” direct sales businesses that have found a new kind of meaning in our age of precarious labor, particularly for women. So-called “mom blogs” are full of companies like LuLaRoe, Pampered Chef and DoTerra, all of which rely on multi-level marketing and direct sales.

Kealing did a large portion of the research for his book in Smithsonian collections: though their relationship fractured in life, the papers of Tupper and Wise, including company memos between the two, as well as physical objects donated from their private collection by descendants, rest together in peace in the Smithsonian archives and the National Museum of American History.

Having both collections shows the two sides to the Tupperware story, Nickles says: the innovative product (which is sold by more than 3.2 million people today) and the ingenious marketing strategy. Referencing both record troves is “like putting the jigsaw puzzle together.”