In the 18th century, French naturalist George-Louis Leclerc, Comte du Buffon (1706-1778), published a multivolume work on natural history, Histoire naturelle, générale et particuliére. This massive treatise, which eventually grew to 44 quarto volumes, became an essential reference work for anyone interested in the study of nature.

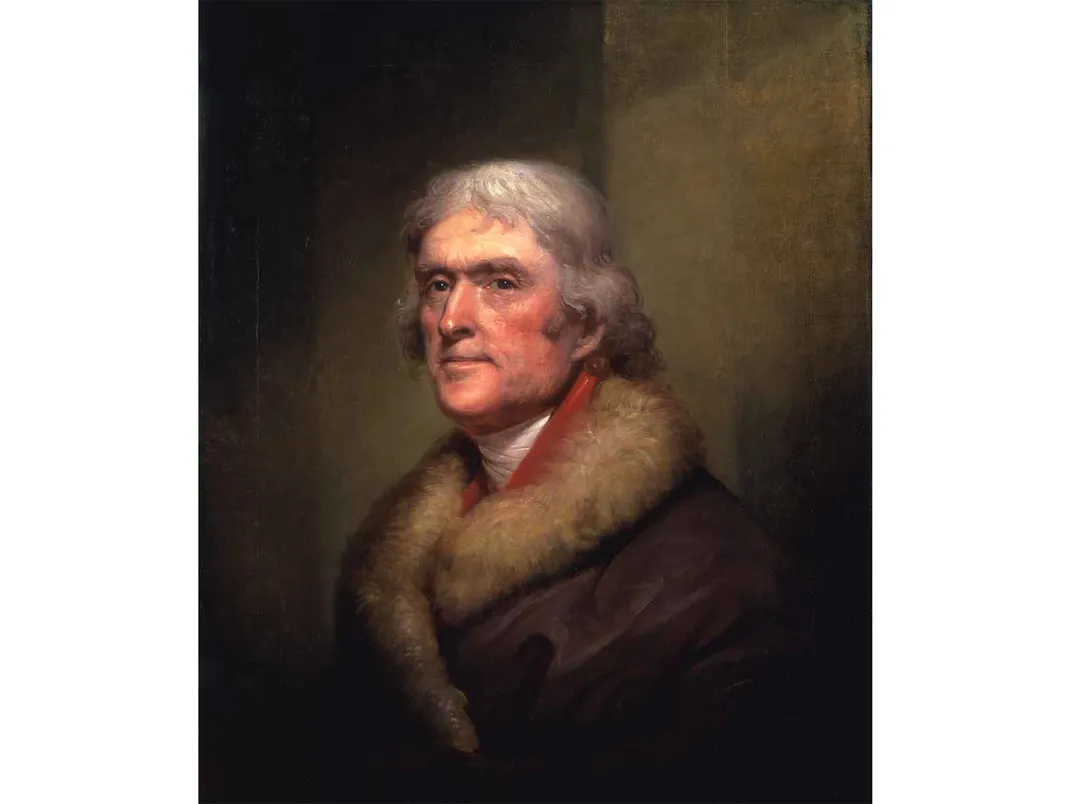

The Comte de Buffon advanced a claim in his ninth volume, published in 1797, that greatly irked American naturalists. He argued that America was devoid of large, powerful creatures and that its human inhabitants were “feeble” by comparison to their European counterparts. Buffon ascribed this alleged situation to the cold and damp climate in much of America. The claim infuriated Thomas Jefferson, who spent much time and effort trying to refute it—even sending Buffon a large bull moose procured at considerable cost from Vermont.

While a bull moose is indeed larger and more imposing than any extant animal in Eurasia, Jefferson and others in the young republic soon came across evidence of even larger American mammals. In 1739, a French military expedition found the bones and teeth of an enormous creature along the Ohio River at Big Bone Lick in what would become the Commonwealth of Kentucky. These finds were forwarded to Buffon and other naturalists at the Jardin des Plantes (the precursor of today’s Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle) in Paris. Of course, the local Shawnee people had long known about the presence of large bones and teeth at Big Bone Lick. This occurrence is one of many such sites in the Ohio Valley that have wet, salty soil. For millennia, bison, deer and elk congregated there to lick up the salt, and the indigenous people collected the salt as well. The Shawnee considered the large bones the remains of mighty great buffalos that had been killed by lightning.

Later, the famous frontiersman Daniel Boone and others, such as the future president William Henry Harrison, collected many more bones and teeth at Big Bone Lick and presented them to George Washington, Ben Franklin and other American notables. Sponsored by President Thomas Jefferson, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark also recovered remains at the site, some of which would end up at Monticello, Jefferson’s home near Charlottesville, Virginia.

Meanwhile in Europe, naturalists were initially at a loss of what to make of the large bones and teeth coming from the ancient salt lick. Buffon and others puzzled over the leg bones, resembling those of modern elephants, and the knobby teeth that looked like those of a hippopotamus and speculated that these fossils represented a mixture of two different kinds of mammals.

Later, some scholars argued that all the remains might belong to an unknown animal, which they called “Incognitum.” Keenly interested in this mysterious beast and based on his belief that none of the Creator’s works could ever vanish, Jefferson rejected the notion that the Incognitum from Big Bone Lick was extinct. He hoped living representatives were still thriving somewhere in the vast unexplored lands to the west.

In 1796, Georges Cuvier, the great French zoologist and founder of vertebrate paleontology, correctly recognized that Incognitum and the woolly mammoth from Siberia were likely two vanished species of elephants, but distinct from the modern African and Indian species. Three years later, the German anatomist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach assigned the scientific name Mammut to the American fossils in the mistaken belief that they represented the same kind of elephant as the woolly mammoth. Later, species of Mammut became known as mastodons (named for the knob-like cusps on their cheek teeth).

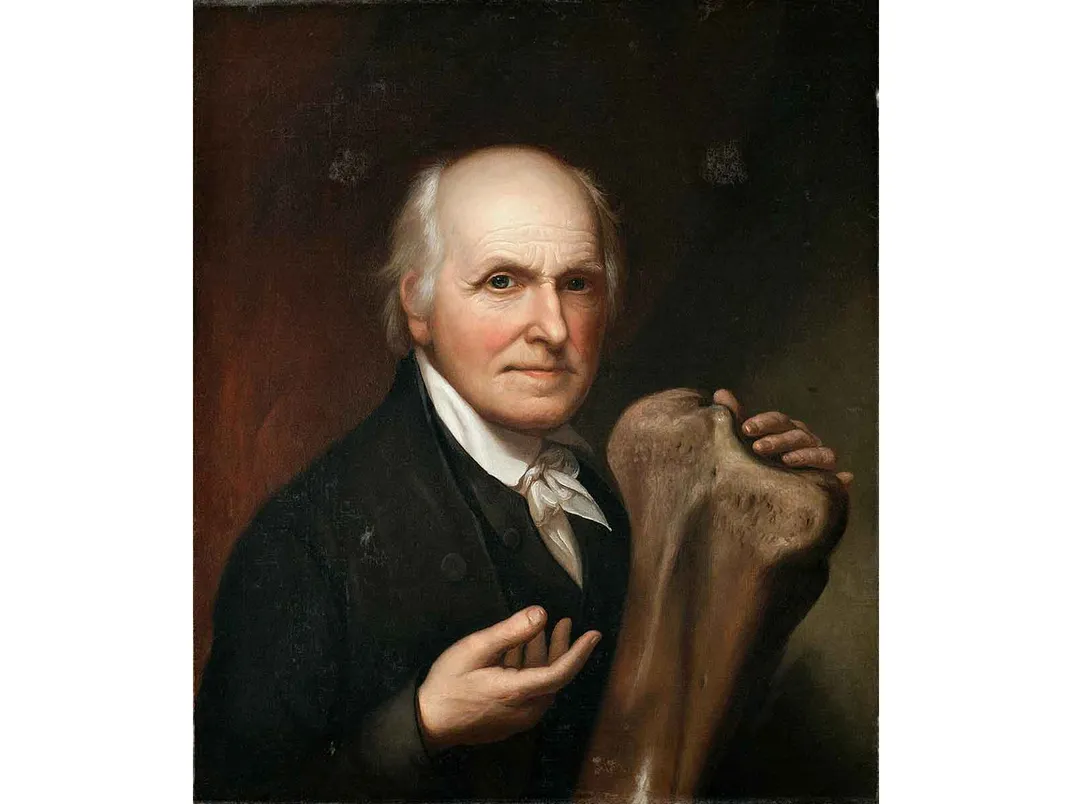

By the second half of the 18th century, there were several reports of large bones and teeth from the Hudson Valley of New York State that closely resembled the mastodon remains from the Ohio Valley. The most noteworthy was the discovery in 1799 of large bones on a farm in Newburgh, Orange County. Workers had uncovered a huge thighbone while digging up calcium-rich marl for fertilizer on the farm of one John Masten. This led to a more concerted search that yielded more bones and teeth. Masten stored these finds on the floor of his granary for public viewing.

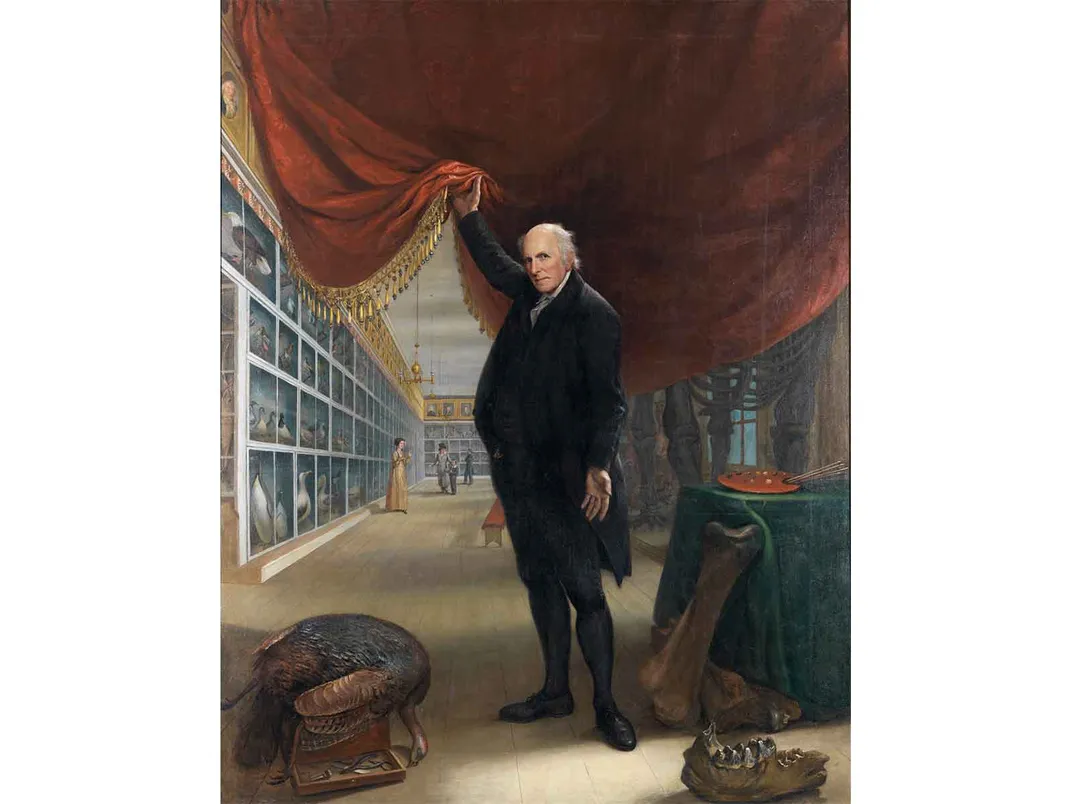

News of this discovery spread fast. Jefferson immediately tried to buy the excavated remains but was unsuccessful. In 1801, Charles Willson Peale, a Philadelphia artist and naturalist, succeeded in buying Masten’s bones and teeth, paying the farmer $200 (about $4,000 in today’s dollars) and tossing in new gowns for his wife and daughters, along with a gun for the farmer’s son. With an additional $100, Peale secured the right to further excavate the marl pit.

To remove water from the site, a millwright constructed a large wheel, so that three or four men walking abreast could provide the power to move a chain of buckets that bailed out the pit using a trough leading to a low-lying area of the farm. Once the water level had dropped sufficiently, a crew of workers recovered additional bones in the pit. In his quest to get as many bones and teeth of the mastodon as possible, Peale acquired additional remains from marl pits on two neighboring properties before shipping everything to Philadelphia. One of these sites, the Barber Farm in Montgomery, is today listed as “Peale’s Barber Farm Mastodon Exhumation Site” in the National Register of Historic Places.

Peale, well-known for the portraits he had painted of several of the Founding Fathers as well as other prominent individuals, had a keen interest in natural history and so he created his own museum. A consummate showman, the Philadelphia artist envisioned the mastodon skeleton from the Hudson Valley as the star attraction for his new museum and set out to reconstruct and mount the remains for exhibition. For the missing bones, Peale crafted papier-mâché models for some and carved wooden replicas for others; eventually he reconstructed two skeletons. One skeleton was exhibited at his own museum—marketed on a broadside as “the LARGEST of Terrestrial Beings”—while his sons Rembrandt and Rubens took the other on tour in England in 1802.

Struggling financially, Peale unsuccessfully lobbied for public support for his museum where kept his mastodon. After his passing in 1827, family members tried to maintain Peale’s endeavor, but ultimately they were forced to close it. The famous showman P. T. Barnum purchased most of the museum’s collection in 1848, but Barnum’s museum burned down in 1851, and it was long assumed that Peale’s mastodon had been lost in that fire.

Fortunately, this proved not to be the case. Speculators had acquired the skeleton and shipped it to Europe in order to find a buyer in Britain or France. This proved unsuccessful. Finally, a German naturalist, Johann Jakob Kaup (1803-1873), bought it at a greatly reduced price for the geological collection of the Grand-Ducal Museum of Hesse in Darmstadt (Germany). The skeleton is now in the collections of what today is the State Museum of Hesse. In 1944, it miraculously survived an air raid that destroyed much of the museum, but which damaged only the mastodon’s reconstructed papier-mâché tusks.

In recent years, Peale’s skeleton has been conserved and remounted based on our current knowledge of this extinct elephant. It stands 8.5 feet (2.6 meters) at the shoulder and has a body length, measured from the sockets for the tusks to the base of the tail, of 12.2 feet (3.7 meters). It has been estimated to be about 15,000 years old.

Mammut americanum roamed widely through Canada, Mexico and the United States and are now known from many fossils including several skeletons. It first appears in the fossil record nearly five million years ago and became extinct about 11,000 years ago, presumably a victim of changing climates following the last Ice Age and possibly hunting by the first peoples on this continent. Mastodons lived in open forests. A New York State mastodon skeleton was preserved with gut contents—pieces of small twigs from conifers such as fir, larch, poplar and willow—still intact.

Peale’s mastodon returned to her homeland to become part of the 2020-2021 exhibition “Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Alexander von Humboldt had collected teeth of another species of mastodon in Ecuador and forwarded them to Cuvier for study. He also discussed them with Jefferson and Peale during his 1804 visit to the United States. The three savants agreed that Buffon’s claim concerning the inferiority of American animal life was without merit.

The exhibition, “Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture,” was on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum September 18, 2020 through January 3, 2021.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/04/f504747a-32a8-496a-9b47-2549e387dcc6/longform_mobilemastodon.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/99/669900e1-d28a-47d0-bfe4-59ed80f942ba/longform_desktop-mastodon.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/HansDS2018.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/HansDS2018.jpg)