The Story of Mexican Coke Is a Lot More Complex Than Hipsters Would Like to Admit

A nasty trade war and questionable scientific assumptions make it difficult to discern what is, and what isn’t, the real thing

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/fa/e2fad037-4480-4792-90fa-7d59a48a07e5/p164mexicancocacolajn20143580web.jpg)

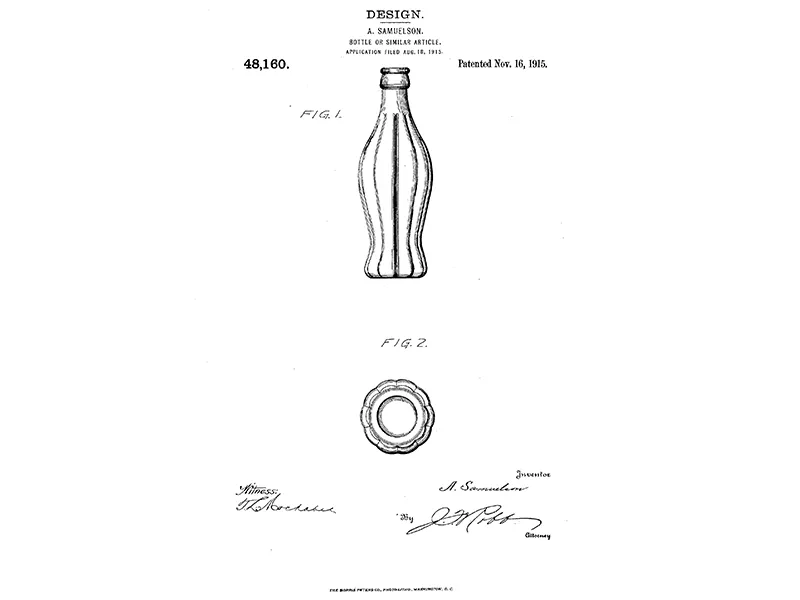

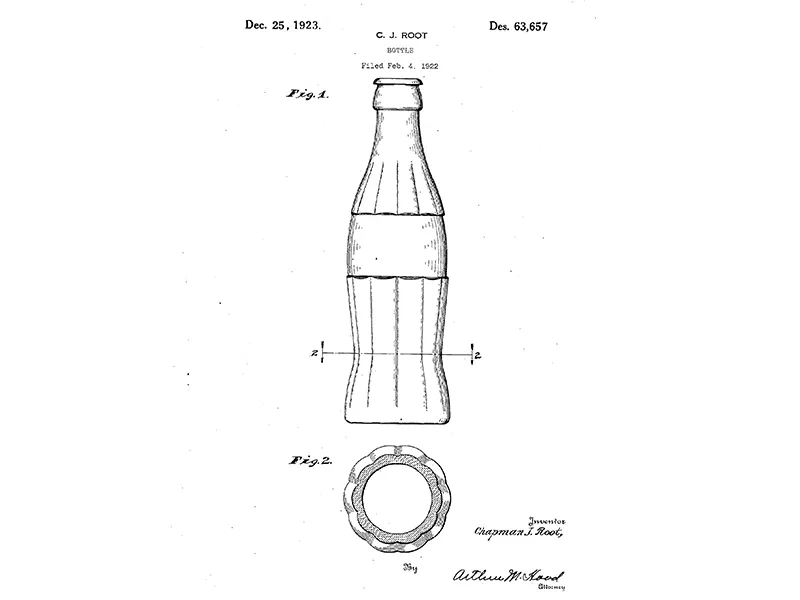

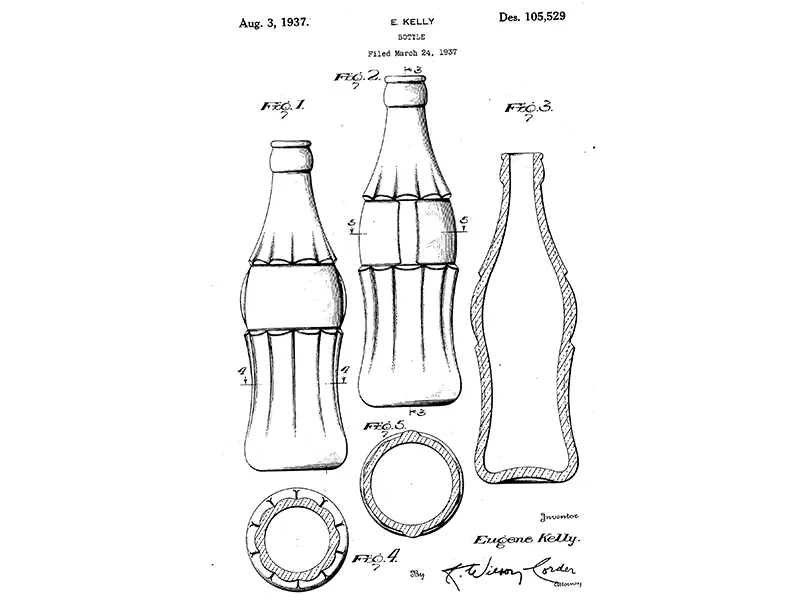

Just as lots of people wanted to buy the world a Coke, as the classic 1970s ad goes, a big chunk of the population today yearns for nothing but "Mexican Coke," seemingly the same brown fizzy liquid in the classically curvaceous bottle—but with one important difference.

Coca-Cola that is hecho en México (made in Mexico) contains cane sugar rather than high-fructose corn syrup, the current whipping boy of the food world. Hipsters and the trendy restaurants they patronize have known about Mexican Coke for some time now, and bodegas in Los Angeles have stocked it to appeal to their Mexican-American customers. But in recent years, Mexican Coke has been appearing in the wide aisles of Costco, signaling a broader interest.

American Enterprise, a new exhibition at the National Museum of American History, features the slender glass bottle, and curator Peter Liebhold says there’s more to the story of Mexican Coke than a simple preference for one kind of sweetener over another.

Mexico and the United States have long been engaged in a trade war over sugar. Sugar is big business in Mexico, as it is in many parts of the world. In an effort to protect its sugar industry, Mexico has repeatedly tried to inhibit imports of high-fructose corn syrup, which the U.S. had been exporting to Mexico and was being used in place of Mexican sugar to make Coke as well as other products.

In 1997, the Mexican government passed a levy on high-fructose corn syrup in an attempt to keep the demand—and thus the price—for Mexican sugar higher. The U.S. deemed this an unfair infringement on trade and went to the World Trade Organization (WTO) to make its case, and the WTO decided in favor of the U.S.

But in 2002, Mexico tried again, enacting a new law calling for a tax on the use of high-fructose corn syrup in the soda industry. Once again, the U.S. went to the WTO, and the organization again ruled in favor of the U.S.

While some say that cane workers in small Mexican villages are being forced out of business and shouldn’t have to compete with American prices, Liebhold says the situation is more complicated than that.

“Although there are some small landholders making a living,” he says, “Mexican agriculture today is very much a remnant of the hacienda system.”

He poses some interesting questions: “If Mexican sugar is supporting a debt-peonage system, is it better to drink a soda made with it, rather than with high-fructose corn syrup? Is it better to support paying workers a decent wage, which is what you’re doing when you drink U.S.-made Coke with high-fructose corn syrup? This love of sodas made with sugar; the more you unpack this, the more unclear it becomes.”

Many foodies and soda lovers swear there’s a discernible difference between Coke made with sugar and Coke made with high-fructose corn syrup—a truer, less “chemical-y” taste; a realer real thing. And they’re willing to pay the higher prices that Mexican Coke purchased in the U.S. commands. Trendsetting chef David Chang, who owns Momofuku Noodle Bar in New York City as well as several other cutting-edge restaurants, was involved in a social-media spat in 2011 when the gastro-sphere lit up at his charging $5 for a Mexican Coke. Chang fought back on Twitter with a simple explanation: “Mexican Coke = hard to obtain in NYC + costs $.”

One truly ironic reason for preferring Mexican Coke’s sugar to American Coke’s high-fructose corn syrup is the idea that sugar is healthier. According to health columnist Jane Brody of the New York Times, “When it comes to calories and weight gain, it makes no difference if the sweetener was derived from corn, sugar cane, beets or fruit juice concentrate. All contain a combination of fructose and glucose and, gram for gram, supply the same number of calories.” She goes on to cite Michael Jacobson of the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Science in the Public Interest, who says, “If the food industry got rid of all the high-fructose corn syrup and replaced it with sugar, we’d have the same problems we have now with obesity, diabetes and heart disease. It’s an urban myth that high-fructose corn syrup has a special toxicity.”

Another of Mexican Coke’s attractions is aesthetic—the glass bottle in which it comes, known internally at the Coca-Cola Company as the “contour bottle,” says Coke historian Ted Ryan (yes, the company has an official historian). The name caught on after a French magazine in the 1930s mentioned “the beautiful Coke bottle with the contoured curves,” amid speculation that it was modeled on a woman’s figure. But, says Ryan, that wasn’t the case: the inspiration was a cocoa pod.

A more serious lure for some Mexican Coke fans may be ideological. After all, as curator Liebhold says, “Coca-Cola is not a mere drink but a repository of cultural meaning and a political statement.” He thinks that Mexican Coke drinkers are expressing an anti-globalization position with their choice of beverage. “They’re anti-brand. Sugar is seen as more globally responsible, anti-big business. But they’re drinking Coke, a huge global brand!”

In the American Enterprise exhibition, the Mexican Coke bottle stands right next to another emblem of the globalization debates: a turtle costume that was an icon of the protests at a WTO meeting held in 1999 in Seattle, Washington. The U.S., trying to do the right thing, had banned the importation of shrimp from countries whose boats didn’t use so-called “turtle excluders.”

But the affected countries appealed to the WTO, saying that the U.S. ban was a trade barrier. The WTO, which had ruled in favor of the U.S. in the Mexican sugar spat, this time decided against the U.S., which had to drop its requirement. Environmental protesters in Seattle wore the turtle suits to express their opinion that local environmental laws should trump international trade law. Similarly, in the sugar rulings, the WTO ruled that the Mexican efforts to protect its homegrown sugar industry against the incursions of imported high-fructose corn syrup were trade barriers. It cuts both ways.

“International versus local—this is a huge issue,” says Liepold. “As you develop a global economy, local desires cease to have as much impact. When you start to have a product that is sent all around the world, the local factory in the community has no control over what they do.”

But Mexican Coke aficionados in the U.S. can control what they drink, and they’re sticking with the glass bottle of the stuff that is hecho en México.

The permanent exhibition “American Enterprise” opened July 1 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. and traces the development of the United States from a small dependent agricultural nation to one of the world’s largest economies.

American Enterprise: A History of Business in America