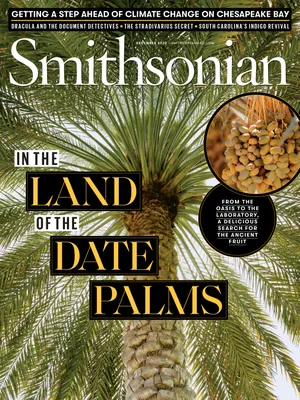

When It Comes to String Instruments, Stradivariuses Are Still Pitch Perfect

Even after three centuries of their existence, the violins spark debate over what makes their sound special

:focal(1307x990:1308x991)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0d/3d/0d3decf7-51ac-4341-9eea-74b660ec3857/novdec2022_e01_prologue.jpg)

More than 4,500 years after an enterprising Mesopotamian stretched a few cords of catgut over a hollow wooden vessel to create the first lute, the craft of building string instruments reached a state of near-perfection in a humble workshop in Cremona, Italy. The craftsman’s name is still known around the world more than 300 years later, though his life story remains something of a mystery: Antonio Stradivari, maker of incomparable violins, cellos and more.

Among the violin virtuosos who play a Stradivarius today are Itzhak Perlman, Akiko Suwanai and Joshua Bell. “I can’t think of anything else that has been frozen in time and stands as the holy grail for modern use,” says Gary Sturm, curator emeritus at the National Museum of American History’s Division of Musical History.

It’s generally agreed that Stradivari was born in Cremona around 1644, and that he began his career around the age of 12. He was long believed to have apprenticed with the famous Amati family, though recent scholarship finds little evidence for this account. Regardless, the Amati designs were the ones to beat, and Stradivari spent nearly 70 years doing just that, creating a prodigious number of instruments—1,200 or so in all, of which some 500 violins, 55 cellos and a dozen violas survive today.

Stradivari began selling instruments around 1665, building his business steadily until Nicolò Amati, the last great artisan in that family, died in 1684, leaving an opening in the growing market for Cremonese violins. Stradivari’s instruments became so coveted that he received commissions from the likes of the Medicis and King James II of England. He married twice and worked out of his house, and unlike other luthiers in this city of musical innovation, he was notable for never using apprentices, teaching his craft only to two of his sons.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/93/ac/93ac6f55-06ff-4edc-b912-4fc6ca8949ef/novdec2022_e28_prologue_copy.jpg)

This “Ole Bull” Stradivarius, made in 1687, is one of five Strads in the Smithsonian collections. It takes its name from its most illustrious owner, Ole (pronounced “oo-luh”) Bornemann Bull, a 19th-century Norwegian concertmaster whom Robert Schumann called the equal of Paganini. It is one of only 10 or 11 decorated violins that survive from Stradivari’s shop. The inlaid and painted designs along the front edges offer a gently mesmerizing geometry, and the sides are decorated with painted foliage. The sound is “sweet” and “flexible,” according to Ken Slowik, the curator of musical instruments at the National Museum of American History. The violin—which came to the Smithsonian on loan in the mid-1980s and entered the permanent collection in 2000—represents “a big step forward in Stradivari’s search for a more powerful concert instrument,” says Rainer Cocron, a violin expert at Ingles & Hayday, a rare instrument auction house.

There’s a longstanding theory that Europe’s Little Ice Age, which lasted from the 14th century until around 1850, is what made Stradivari’s creations special: As the theory goes, slower tree growth created denser woods with narrower grains that conveyed a richer sound. But Stewart Pollens, former conservator of musical instruments at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and author of two books about Stradivari, says, “I’m not a big believer in the Little Ice Age business,” mainly because when you inspect Stradivari’s wood today, you’ll find all manner of different densities: “Sometimes the grain is quite broad, and sometimes it’s very narrow.”

Scholars have argued that the secret might be in Stradivari’s mode of treating his wood, including his varnishes. This line of thought was energized by a 2006 study in Nature by Joseph Nagyvary, professor emeritus of biochemistry at Texas A&M University. Using nuclear magnetic resonance and infrared spectroscopy to analyze the instruments’ wood, Nagyvary found that metallic salts may have played a role in these instruments’ nuanced tones. Another study released last year bolsters the idea that varnishes and oils contributed to the Stradivarius magic.

Pollens and Cocron say the truest explanation is the simplest: Stradivari was a fastidious craftsman who undertook smart experiments with geometry and wood thickness, perfecting flatter arching on the front and back to create violins with much more power than any before. Indeed, Stradivari’s instruments made it possible for the music to reach every corner of large concert halls and thereby helped usher in the symphonic age of Mozart, Beethoven and Tchaikovsky. Stradivari “anticipat[ed] the growing role of the violin as a solo instrument and brought violin-making to new heights,” says Cocron, who marvels at “how attuned [Stradivari] was to musical trends.”

By the time Stradivari died in 1737, his skill and foresight had made him a rich man. His instruments are still valuable commodities—in June, a 1714 Strad sold for $15 million—and today’s top players are still drawn to them. “There’s a bottomlessness to the possibilities,” says renowned cellist Evan Drachman, who played his first Stradivarius cello at 18 and whose grandfather was the celebrated Ukrainian-born cellist Gregor Piatigorsky. James Ehnes—a violin soloist who serves as artistic director of the Seattle Chamber Music Society and visiting professor at the Royal Academy of Music in England—estimates he has played more than 150 Strads. He describes the experience as a cinematic epiphany: “It really was a bit like The Wizard of Oz, everything being in black and white and then in color.””