Studying the Climate of the Past Is Essential for Preparing for Today’s Rapidly Changing Climate

A Smithsonian scientist explains why in the new Age of Humans, we must turn from crisis management to planet management

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/95/0b/950beb3a-59fa-4220-8b5e-d9e641d0ccc8/photo_1_scottlizdino2sw0507.jpg)

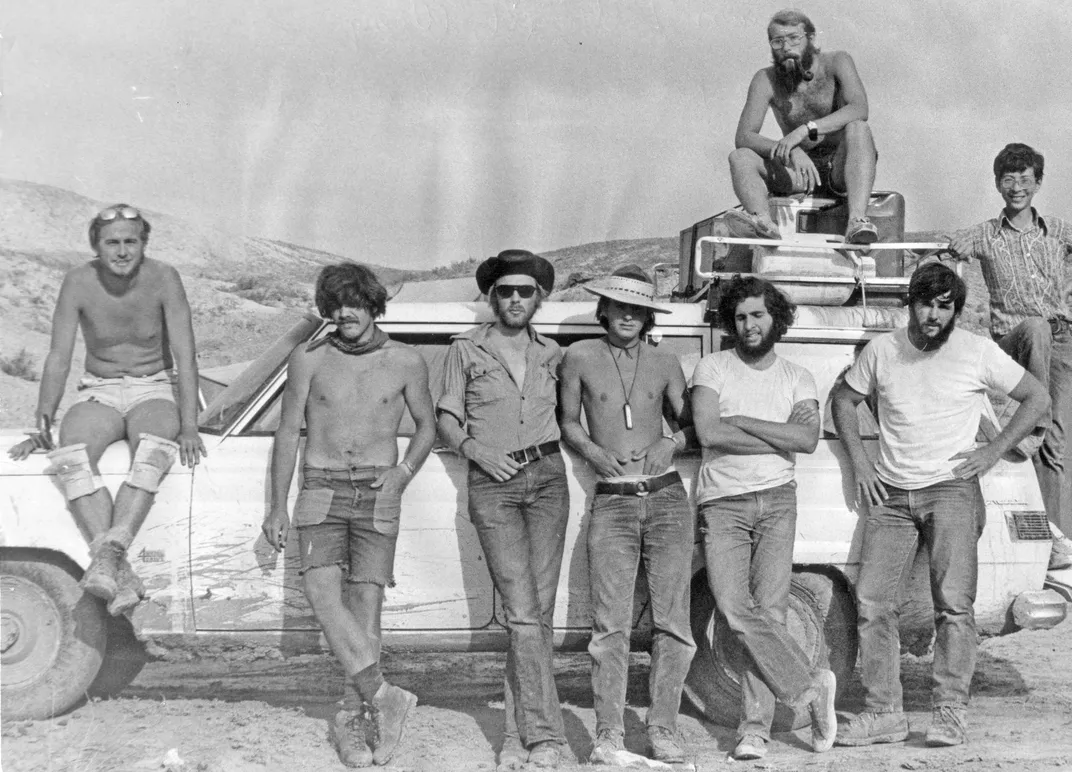

In 1942 Winston Churchill said: “The longer you can look back, the farther you can look forward.” And indeed, many cultures study history for political and military insight. I study fossils that are millions of years old because I am concerned about the future. As a paleontologist, I think it is time to establish a tradition that uses geological history to anticipate—and thus plan for—the future.

I didn’t always think this way. I became addicted to finding fossils because it was a kind of exploration, and because I loved the feeling of being transported through time simply by walking up and down the layered hillsides of Wyoming and Montana.

I continued in this happy phase of exploration through the first decade of my career. But things changed in 1990, when two climate scientists published a map—a computer simulation of global climate 50 million years ago. It showed a relatively cold world—winters that fell below freezing across northern Asia, Europe and North America.

I knew this map had to be wrong. For 100 years we paleontologists had been finding fossils that demonstrated winters were very mild in this time period, even in the Polar Regions and in the middles of continents at high latitudes.

We had found dawn redwood forests on the shores of the Arctic Ocean.

We had discovered fossil palm remains along the coast of Alaska.

In the middle of North America, where winters are bitter cold today, we had found fossils of alligators.

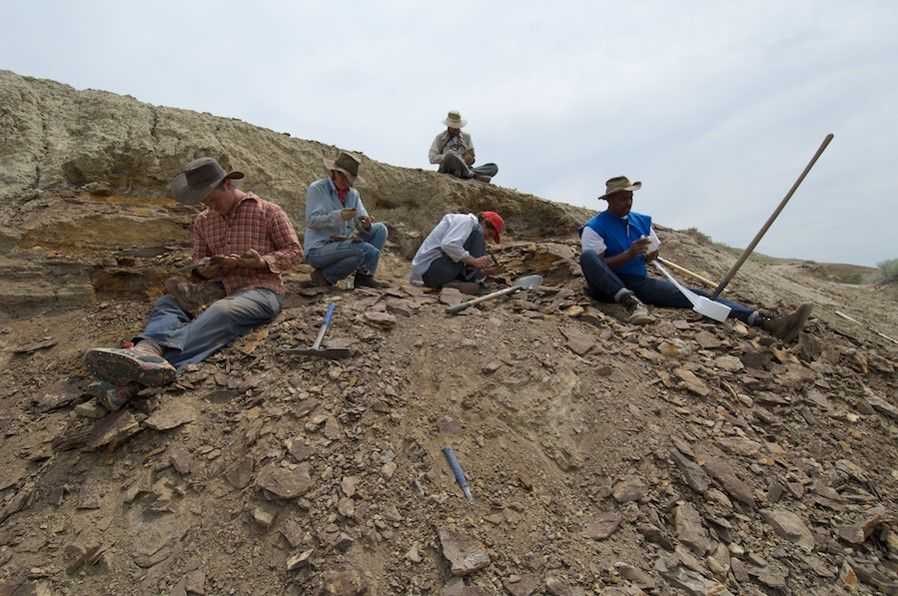

This is when it dawned on me that studying fossils was far more relevant than I had realized. Fossils test our understanding of how the planet works—they contain clues that improve our ability to predict climate, in both the past and in the future. I still loved finding fossils, but unlocking these clues became my new obsession.

For the last 25 years climate modelers and geologists have been working back and forth on this problem of how to explain the warm climates of the past. Today’s computer simulations agree better, though still not completely, with climate reconstructions from fossils and other evidence.

The result of this fertile argument between climate modelers and paleontologists is that the past has become a proving ground for hypotheses about how climate and other earth systems work. And the beauty of testing our understanding against what has already happened—the fossil record—is that we can find out if the models work, without waiting for decades or even centuries to pass. This is particularly important because the problems we face are urgent.

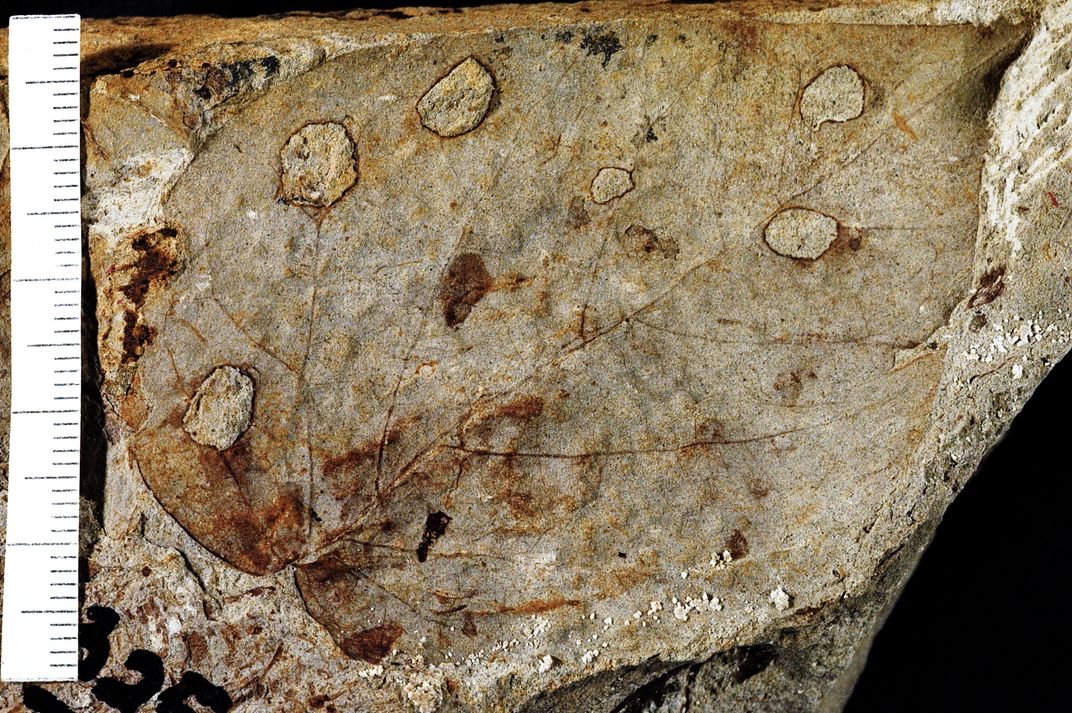

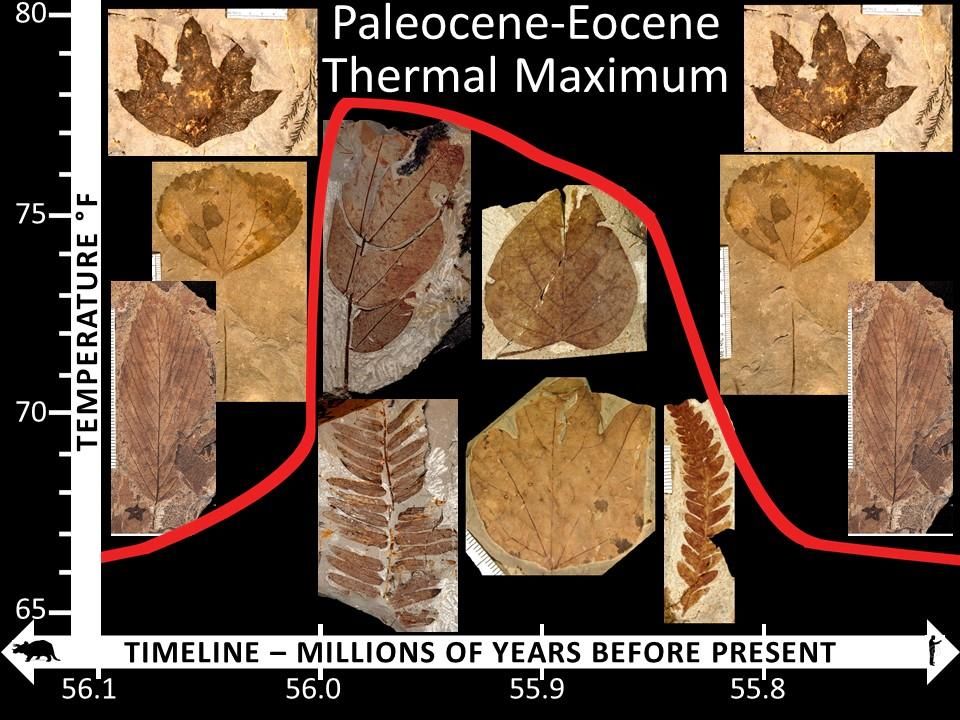

The geological record has proved to be a great place to test our ideas about Earth processes, but it also has produced surprises. Over the last few decades scientists have discovered a new kind of event in Earth’s climate history—planetary heat waves that lasted for thousands or hundreds of thousands of years.

The biggest of these occurred 56 million years ago, and it’s called the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, or PETM.

The PETM was kicked off by a release—likely from methane stored in sea floor sediments—of 5,000 billion tons of carbon into the ocean and atmosphere—the amount we would generate if we were to burn the entire known modern-day fossil fuel reservoir. The release about doubled the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere.

This triggered a host of events: global temperature rose by 5 to 8 degrees C; the ocean became more acidic; warmer climate led to warmer soils, and warmer soils to faster decay of plant matter, which released even more CO2 to the atmosphere. With the slow rate at which CO2 is removed from the atmosphere by weathering and other processes, the PETM lasted 150,000 years.

During that time, many small deep-ocean species went extinct. The Arctic warmed so much that plants and animals moved across high-latitude land bridges between the northern continents. And there were massive die-offs of local populations of plants in mid-latitudes.

The parallels between the PETM and the present are strong. Though today’s world, with its vulnerable ice caps, is probably more sensitive to a carbon release than the world of 56 million years ago. But the biggest difference between the PETM and today is that we are adding CO2 in the atmosphere. We can change it.

CO2 levels are now 40 percent higher than they were before the industrial revolution. If we go for business as usual, the rest of this century will be like the start of the PETM on steroids—a similar or larger CO2 increase happening 10 times faster. What few realize is that this rise in CO2, and the heat wave it will cause, will persist for thousands or tens of thousands of years. As we have seen, that’s the way the planet works.

The long history of our planet makes you realize that change is inevitable, but it also shows you that the changes we are causing now are very large, exceptionally fast, and mind-bogglingly persistent. The consequences of what we do in the next decades will be felt for tens of thousands of years to come. That’s the most awesome responsibility imaginable, but it comes with our power to change the global environment.

In one sense, I’m an optimist. We aren’t going to destroy the planet or drive ourselves extinct. With more than 7 billion people and 75 million more every year, human extinction is hardly our problem.

But examples of extreme environmental change from the past suggest that there is likely to be hardship and misery coming for billions of people. And we are already diminishing the diversity of life and compromising the ability of ecosystems to produce the resources we depend upon.

We are now as powerful as geological forces were in the past. So we have to learn to think on the planet’s timescale, not our own. We must turn from crisis management to planet management, but we will only do that when we realize our actions are not just for today, but for the ages. I hope people of the future will look back on us and see that we learned the lessons of deep time.

Editor’s Note: Adapted from a talk Scott Wing gave at the Annual Meeting of the New Champions 2016, the World Economic Forum’s Global Summit on Innovation, Science and Technology. The Smithsonian Institution partners with the World Economic Forum to broaden awareness of cultural heritage protection and preservation, science, health, technology, and other critical global issues. The World Economic Forum, committed to improving the state of the world, is the International Organization for Public-Private Cooperation. The Forum engages the foremost political, business and other leaders of society to shape global, regional and industry agendas. The Forum is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SLW_photo_-James_Kegley_for_Smithsonian.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SLW_photo_-James_Kegley_for_Smithsonian.jpg)