Take an Exclusive Sneak Peek Inside the Renovated Freer Gallery, Reopening in October

Charles Lang Freer gifted this meditative haven for art lovers to the nation and was James McNeill Whistler’s friend and patron

At the turn of the 20th century, European art dominated the market—and the walls of world-class galleries. Although railroad magnate Charles Lang Freer appreciated the work of these Old Masters, he wanted to define a new aesthetic: high-quality art that was equally beautiful and technically masterful but far more obscure. The Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art, an eclectic cross-cultural collection housed in a Renaissance-style palace, is the result of this mission.

More than 100 years after Freer amassed his vast collection of Asian and American art, his namesake art gallery on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. retains his eclectic character. A mix of classical and Middle Eastern architecture identifies the building as an anomaly amidst the surrounding Brutalist structures. Galleries within the museum reveal a similarly distinctive philosophy.

The Freer Gallery of Art has experienced significant change over the years, most prominently the 1987 addition of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and a major renovation set to conclude this fall, but its unique nature remains intact.

This summer, Smithsonian.com reporters took an exclusive, behind-the-scenes tour of the Freer Gallery, which has been closed for renovations since January 2016. Richard Skinner, the Freer's museum project manager, shared insights about the gallery’s refurbishment, as well as its unique architectural history. Andrew Warner, a Smithsonian.com photographer, shot exclusive photographs of the building in its preparatory state.

When the Freer opens its doors on October 14 (IlluminAsia, a free, weekend-long festival of Asian art, food and culture will celebrate the reopening with food stalls, live performances and a night market), it will include improvements the founder himself would have appreciated: Gallery walls, floors and more have been restored to their original appearance, technical updates have been subtly masked, and the museum’s status as a serene haven from the bustle of D.C. remains apparent.

Charles Lang Freer was one of the Gilded Age’s archetypal self-made men. Born in Kingston, New York, in 1854, he began his career as a clerk before moving up to railroad bookkeeper and eventually manager. After moving to Detroit in 1880, Freer and his business partner Frank Hecker established a successful railroad car manufacturing company. Armed with newfound wealth, Freer turned his attention to a different passion: art collection.

Lee Glazer, the Freer's curator of American art, explains that collecting was a popular pastime for the well-to-do. Freer’s collection began as a display of status, but it transformed into a zealous fascination.

In 1887, one of Freer’s acquaintances introduced him to the work of James McNeill Whistler. The artist was a leading adherent of the Aesthetic Movement and championed beauty as art’s most important quality. Freer, captivated by Whistler’s paintings and artistic philosophy, became one of his greatest patrons. He also began purchasing the work of Whistler’s American contemporaries, thereby defining a key element of his collection: art for art’s sake, or more specifically, American Aesthetic art.

“He had an independent streak, an aesthete sensibility that really compelled him to look toward the obscure and the exceptional,” says David Hogge, head of archives at the Freer Gallery. “He was always . . . trying to stay one step ahead of the crowd.”

Freer embraced American art when others were collecting Old Masters and, in the 1890s, made another unique discovery. According to Glazer, Freer realized that Whistler’s work shared points of contact with Japanese woodblock prints. The artist explained that these prints were part of an older, rarefied tradition and made Freer promise to find more of the continent’s rare treasures—Whistler himself died in 1903 without ever setting foot in Asia.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a9/a6/a9a6b30c-9fff-4a9d-b0ca-125b523d965c/fs-fsa_a01_120151.jpg)

Spurred by Whistler’s love of Asian art, Freer made his first trip to the continent in 1894. He would make multiple return trips over the following decades, eager to expand on his collection of Chinese and Japanese paintings, ceramics and other artifacts.

By 1904, Freer owned one of the country’s most preeminent art collections, and he decided to share it with the public. Unfortunately, the Smithsonian’s response to his proposed donation was tepid at best. Pamela Henson, the director of institutional history at the Smithsonian Institution Archives, says the science-focused group was wary of devoting resources to an art museum. After two years of negotiations, plus a nudge from President Theodore Roosevelt, the Smithsonian finally accepted Freer’s offer.

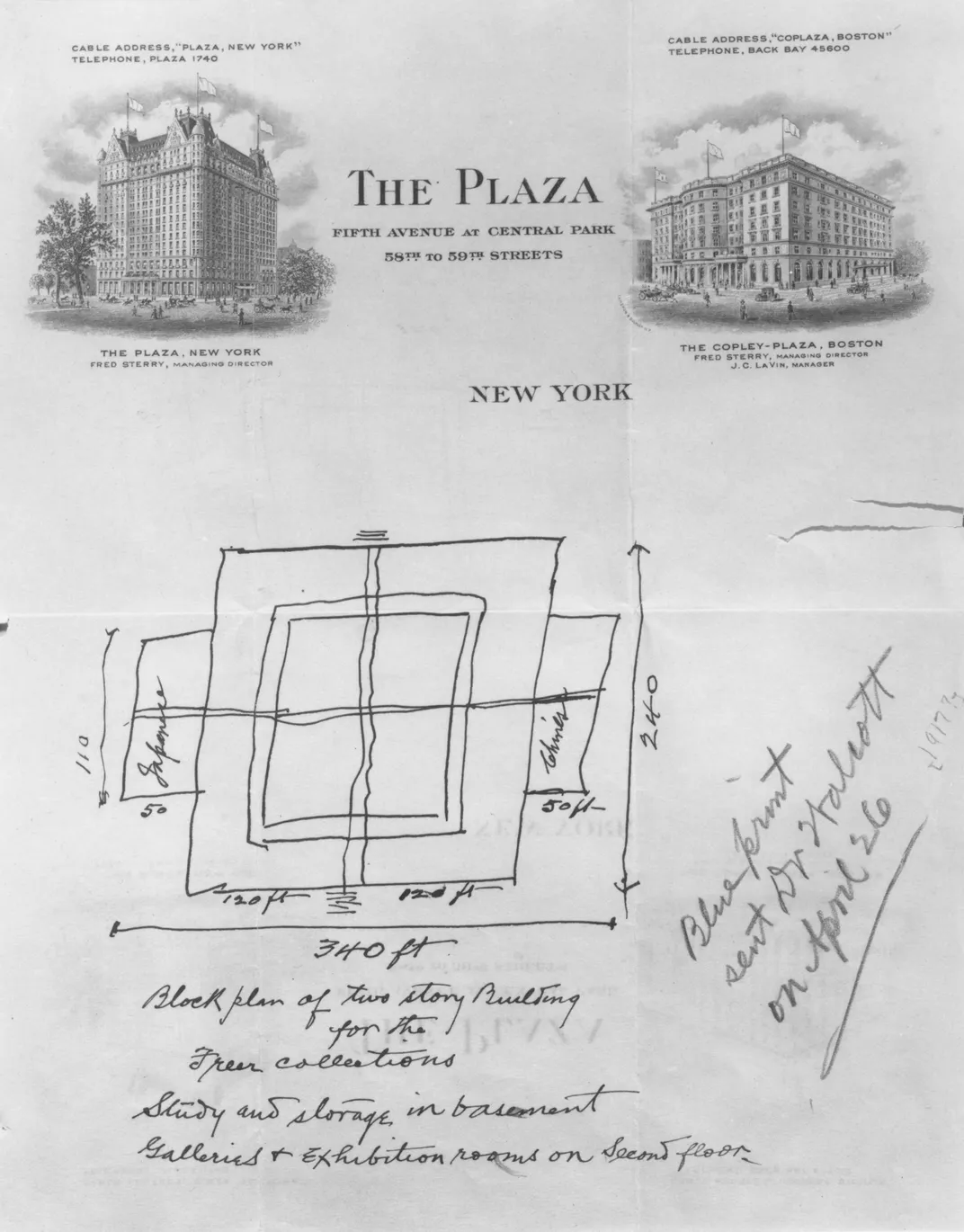

Prior to construction, Freer traveled to Europe in search of architectural inspiration. Glazer says he was largely unimpressed but settled on an Italian Renaissance design based on a palazzo in Verona. He also studied other galleries’ display techniques and, according to Hogge, filled a notebook with design suggestions. During a New York City meeting with the gallery’s architect, Charles Platt, Freer even sketched a rough floor-plan of his envisioned museum on Plaza Hotel stationery.

The relationship between Freer and the Smithsonian remained tenuous. Freer had a vision for his collection and placed limitations on its curation. The Smithsonian was slow to progress with the project despite receiving Freer's generous funding. Construction halted until 1916, and wartime delays pushed the opening to 1923. By then, the titular donor had been dead for four years.

Still, Freer’s influence is visible from the moment visitors enter the gallery. Behind the Renaissance-style exterior is a quixotically intimate yet grand environment. As Skinner explains, the building is a “unique synthesis of classical Western and Eastern sensibilities.”

An interior courtyard (once populated by living peacocks, a tribute to Whistler’s famed Peacock Room) stands in the middle of the space, encircled by exhibition galleries and vaulted corridors. Natural light enters the galleries through massive skylights, and dark floors highlight the artifacts on display. Visitors travel from one gallery to the next via the central corridor and catch a glimpse of the courtyard through towering glass panels. Refreshed by this mini-break, they are better able to appreciate the next exhibition.

William Colburn, director of the Freer House, oversees the industrialist’s Detroit mansion. (The house, currently owned by Wayne State University and occupied by the Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute, reflects its storied past through periodic public events and tours.) Until his death in 1919, Freer held his collection at his home. He carefully refined the array of artifacts, purchasing new items and removing those unworthy of a national collection, and experimented with presentation strategies seen in the D.C. gallery. As Colburn explains, Freer wanted viewers to have a meditative experience subtly guided by the design of the space.

The Freer Gallery’s architectural features are complemented by the scope of its collection. Glazer says that Freer believed in a universal art spirit, meaning “the language of art could transcend differences of time and space and culture, and the best art of the past somehow spoke a common language with the best art of the present.” He thought it was natural to display Chinese scrolls and prehistoric jade alongside Whistler paintings, as they represented the best of their respective eras.

At the time, Asian artworks were treated as ethnographic objects rather than fine art. By placing American and Asian art in conversation with one another, especially in a museum designed to resemble a Renaissance palazzo, Freer hoped to show the works were of equal quality.

Colburn says, “On one wall, he’s presenting modern American art of his own day, and on the other wall he’s presenting Asian art. In the same room, in the same space, the art is in dialogue with each other: east and west, contemporary and ancient.”

Today, the Freer Gallery is a modernized version of the building its founder envisioned. Freer placed extensive limitations on the collection—acquisitions of Asian art are carefully monitored, the American art collection cannot be expanded, works cannot be lent to other galleries and works from other collections cannot be displayed alongside Freer’s—but the 1987 addition of the Sackler Gallery gave curators some creative freedom.

The two museums are connected by an underground passageway and share a focus on Asian art. The Sackler, however, operates without the Freer’s restrictions, and Glazer says the “boundaries between the two museums have become much more porous over the years.”

Hogge adds that the modern museum is different than galleries of Freer’s time. “There’s a lot more traveling shows, a lot more need to bring art collections in comparison with other people’s collections, so we borrow and loan. The Freer bequest limited us from that, which is how the Sackler came to be.”

The Freer and Sackler Galleries of Art reopen on October 14. A free, two-day festival, IlluminAsia, of Asian art, food and culture will celebrate the reopening with food stalls, live performances and a night market.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0f/44/0f44ccf8-a4ed-4430-b273-1fdba07b5b4a/l1070525.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/dd/57ddf1a6-fbf6-403f-a660-373ab6123b85/l1070356.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)