It’s not what you’d expect from an art show. At the end of a long corridor, beyond a pulled-back heavy burgundy brocade curtain, a full-scale mastodon skeleton fills much of the rotunda-like space of the gallery. The fossil is the centerpiece of “Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture,” a much-anticipated exhibition that was poised to open at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) with much fanfare earlier this year just as the COVID-19 crisis shuttered the museum.

The show with its stately mastodon will now open to the public Friday, September 18, as the museum reopens, ready to receive ticketed visitors, who follow the new Smithsonian health guidelines, wearing masks and practicing safe social distancing.

The museum's senior curator Eleanor Jones Harvey purposely placed the 11-foot tall, 20-foot long elephant ancestor in the gallery as an uber statement on what polymath Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) meant to the American politicians, scientists, artists and writers who fawned over him during his brief six-week visit to the United States in 1804, and who became a part of his global network of admirers for a huge chunk of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The mastodon was a coup for SAAM—it is the first time the fossil will be back in America since 1847, when it made its way through Europe and ultimately ended up at The Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt in Germany. A video shows the disassembly in Darmstadt and three-day reassembly at the museum.

Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture

A Prussian-born geographer, naturalist, explorer, and illustrator, Alexander von Humboldt was a prolific writer whose books graced the shelves of American artists, scientists, philosophers, and politicians. Humboldt visited the United States for six weeks in 1804, engaging in a lively exchange of ideas with such figures as Thomas Jefferson and the painter Charles Willson Peale.

The mastodon—exhumed under the guidance of artist Charles Willson Peale and cobbled together with wood by a leading sculptor of the day—represents the intersection of art, culture and science, says Harvey. Similarly, Humboldt studied multiple disciplines and believed that “artists need to have enough scientific background to know what they are painting, and scientists should maintain a sense of aesthetic wonder to appreciate as they are collecting,” Harvey says.

Almost 300 plants and 100 animals are named after the Prussian-born naturalist. Have you heard of the Humboldt penguin? The Humboldt Squid, which swims in the Humboldt Current? How about the Humboldt lily, found in California, which also has a Humboldt County? Forests, rivers, peaks, mountain ranges and even a patch of plains on the moon have been named for him. Humboldt, who published 36 books, including his five-volume masterpiece, Cosmos, was a man of many interests—so many that it’s hard to catalog them all.

He mentored many young scientists and accumulated a vast network of admirers and collaborators through some 25,000 letters, often beseeching others to share findings from their explorations as a means of accumulating data to prove his “unity of nature” theory: that everything on the planet is interconnected, says Harvey. Humboldt may have been one of the first to warn about climate change, noting that the devastation of forests in Venezuela had changed the local climate.

Read more about Alexander von Humboldt in this article by Eleanor Jones Harvey

“He’s really one of the last great enlightenment scientists and one of the first great modern scientists,” Harvey says, noting that his work was grounded in meticulously analyzed data.

Humboldt’s holistic perspective—and his desire to make people understand nature’s importance to humanity—is more relevant than ever, notes Hans-Dieter Sues, chair of paleontology at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, in the preface to the exhibition catalogue.

Most present-day scientists “tend to focus on specific ecological changes without considering the complex web of interactions between humans and the environment,” writes Sues. Environmentalists also concentrate too much on the preservation of a particular species, “rather than taking a more integrated approach that also considers humans.”

“There is an urgent need for a Humboldtian perspective if we are to understand and address the unparalleled crisis now facing our species,” Sues writes.

It’s hard to overstate Humboldt’s popularity during his heyday—the late 18th and early-to-mid-19th centuries. Widely traveled and broadly known in Europe, he was able to secure backing from the King of Spain to travel throughout South America, Mexico and Cuba between 1799 and 1804, documenting plant life, geology, climates, peoples and discovering the location of the magnetic equator, allowing him to “recalibrate his equipment and take the most accurate readings to that point of longitude and latitude in the Americas,” according to Harvey.

His book, Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent during the Years 1799–1804, and other writings, excerpted in newspapers, gained him fans in the United States. Humboldt arranged a stopping over in America at the end of the southern hemisphere journey, primarily to meet President Thomas Jefferson, who “he suspected was his intellectual equal,” but also to get a close-up look at democracy and to possibly explore the Louisiana Territory, says Harvey.

He was greeted like a rock star by Peale when he disembarked in Philadelphia and feted by other intellectuals during his visit. He arrived in America at an auspicious time, says Harvey. Humboldt believed that the nation should capitalize on its natural wonder—that places like Niagara Falls and Natural Bridge in Virginia (on land owned by Jefferson) were just as monumental as European castles and cathedrals.

The Peale mastodon—exhumed in upstate New York in 1801—fed into the mythology Jefferson hoped to create: that everything in America was bigger and better. Mammoth mania took over America after Peale displayed the fossil at his Philadelphia museum in late 1801. The unearthing of the bones is magnificently recalled in Peale’s 1806 painting, Exhuming the First American Mastodon.

Humboldt had written to Jefferson hoping to finagle an invite to the White House by mentioning that he’d found some mammoth teeth in the Andes. It worked, and he soon found himself hobnobbing with a network of American politicians, painters, writers and scientists. Among those who became a part of the Humboldt Hive: James Fenimore Cooper, Edgar Allan Poe, John Muir, Henry David Thoreau, Frederic Church, Walt Whitman and Samuel F.B. Morse.

The Prussian eventually came to consider himself half-American. Though he never visited the U.S. again after the 1804 trip, American luminaries frequently came to his Paris residence to bask in his presence. By 1847, Humboldt had been made a member of seven American scientific and cultural organizations.

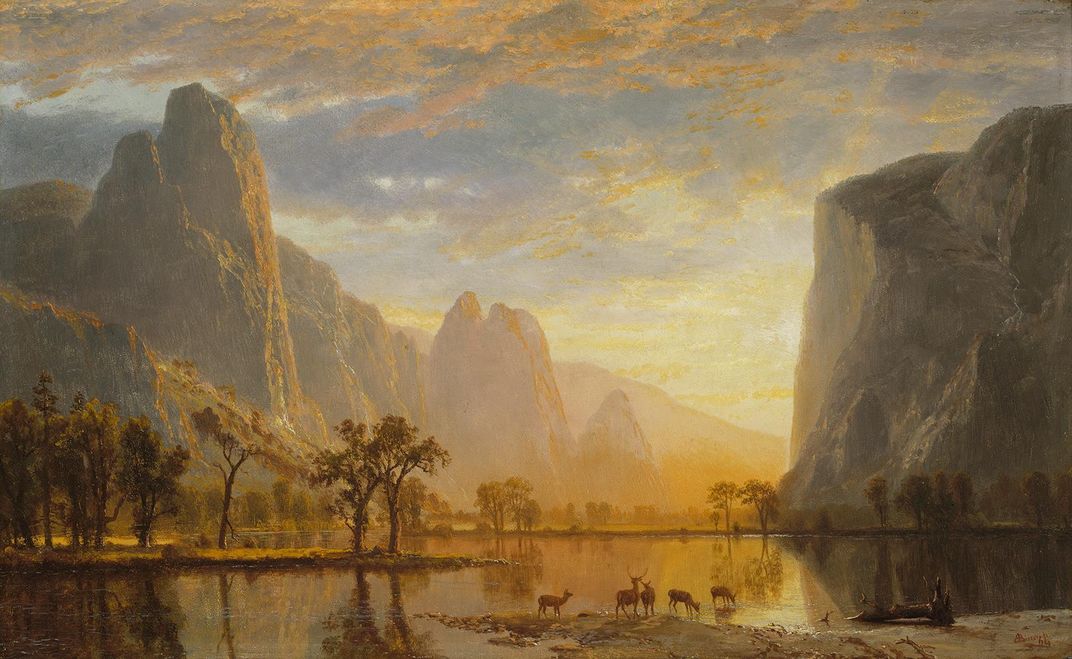

Humboldt inspired a bevy of artists to ground their work in nature, including some of the greatest landscape painters of the time, Albert Bierstadt and Church. Twenty works by Church and two of Yosemite by Bierstadt are featured in the exhibition. Church’s paintings of Niagara Falls, Natural Bridge, and several Andean peaks, which he visited during a trip that recreated, step-by-step, Humboldt’s expedition through the same region, transport the viewer into a towering vision of nature.

Throughout his travels and his life, Humboldt was an advocate for social justice. “He thought the one flaw in American democracy was that it would not abolish slavery,” says Harvey. He urged James Madison to consider ending slavery, telling him that “nature is the domain of liberty.” Humboldt backed the anti-slavery 1856 presidential candidacy of John C. Fremont—who, during earlier explorations of the American west that were inspired by Humboldt, paid tribute to the scientist by naming various features after him, including a river in Nevada.

The plight of Native Americans also concerned Humboldt, especially in the wake of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. He convinced Prince Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied, a protégé, and artist Karl Bodmer, to replicate part of the Lewis and Clark expedition to document the tribes of the Upper Missouri River. The exhibition features excerpts from the Prince’s journals and finely detailed watercolors of tribe members executed by Bodmer.

Humboldt also became friends with artist George Catlin, who had begun immersing himself in the documentation of America’s vanishing tribes starting in 1830. They meet in Paris, where Catlin has brought his portraits of Native Americans and a group of people from the Iowa tribe to educate the French—and shore up his dwindling finances. “It is the first and only time Humboldt will meet North American Indians,” says Harvey. Humboldt ends up touring the Louvre with some members of the tribe, one of whom kept a diary of the events of that trip.

A number of original Catlin portraits are on display, as is an 1845 painting depicting the visit to France, Karl Girardet’s Danse d’indiens Iowas devant le roi Louis-Philippe aux Tuileries (Dance of the Iowa Indians before the King Louis-Philippe at the Tuileries).

Not surprisingly, Humboldt is even connected with the founding of the Smithsonian Institution. When the Prussian traveled to England in 1790 to connect with a mentor there, he also ended up being introduced to a young chemist, James Smithson—the same Smithson whose bequest eventually created the Smithsonian in 1846.

The two reconnected in Paris in 1814, and spent a year in friendship, hanging out with liberal pro-American and pro-Democracy factions—making Smithson a bit of an outlier among his British compatriots. Humboldt and Smithson shared a love of collecting and analyzing, and spreading knowledge.

Well before the Smithsonian was established, Peale had already envisioned a national institution dedicated to the arts, sciences and American ideals and asked Humboldt to convince Jefferson to buy his museum collection as the foundation. Jefferson wasn’t interested in purchasing Peale’s materials. But the idea of a national institution continued to be discussed in Washington and elsewhere for decades. In 1835, Smithson's last heir died and the estate was then, as directed by Smithson, bequeathed to the U.S. After much debate, Congress decided to accept the money. American attorney Richard Rush was dispatched to London to bring the dollars home, to, as Smithson put it, "found at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an Establishment for the increase & diffusion of knowledge among men.”

Those words “are a Humboldtian credo,” writes the museum’s director Stephanie Stebich in the introduction to the exhibition catalog. Most of the men ultimately involved in setting up the Smithsonian Institution had either known Humboldt, corresponded with him, or admired him, says Harvey.

“The entire Smithsonian is in some ways the bricks and mortar realization of everything that Humboldt cared about,” she says. The Institution’s 19 museums, the National Zoo, and 21 research centers and programs encompass Humboldt’s vast interests.

To make that point, the final gallery in the show features nine ongoing Smithsonian projects “that reflect Humboldtian enterprise,” says Harvey.

Though Humboldt was celebrated throughout the 19th century—with big parties in American cities every decade starting in 1869—the rise of Germany as a hostile power in the early 20th century caused Americans to stop teaching about the great scientist. Essentially, the lights went out on Humboldt, says Harvey.

“I’m trying to turn the lights back on and dust for his fingerprints, and say, ‘hey, he was here, and here and here,’” she says.

The exhibition “Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture” was on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum September 18, 2020 through January 3, 2021.

Listen to Sidedoor: A Smithsonian Podcast

It took a zealous Prussian explorer to show the colonists what they couldn’t see: a global ecosystem, and their own place in nature. Check out this season five episode, "The Last Man Who Knew It All," about Alexander von Humboldt.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8b/db/8bdb714b-8035-4881-b491-187214c50018/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/13/55135988-d21d-4b8c-8302-68b7f13bc38c/social_media_dimensions.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)