Telling the Story of 19th-Century Native American Treasures Through Bird Feathers

Famed explorer John Wesley Powell’s archive of his 19th century travels is newly examined

It’s a chilly winter day as Carla Dove loads up her Subaru Impreza with 25 or so taxidermied owls, ravens, hawks, ducks and other birds, for a short trip out to the Smithsonian’s Museum Support Center (MCS) in Suitland, Maryland.

Dove, along with Marcy Heacker, a colleague from the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History’s Feather Identification Lab, is going to meet two anthropologists, who need her help in figuring out what kinds of bird feathers have been used to decorate a variety of Native American artifacts.

When Dove gets to the anthropology lab on the MSC’s second floor, she finds an array of headdresses, deerskin skirts and leggings, bow and arrow cases and other articles of clothing neatly laid out on a long white laminate-topped workbench.

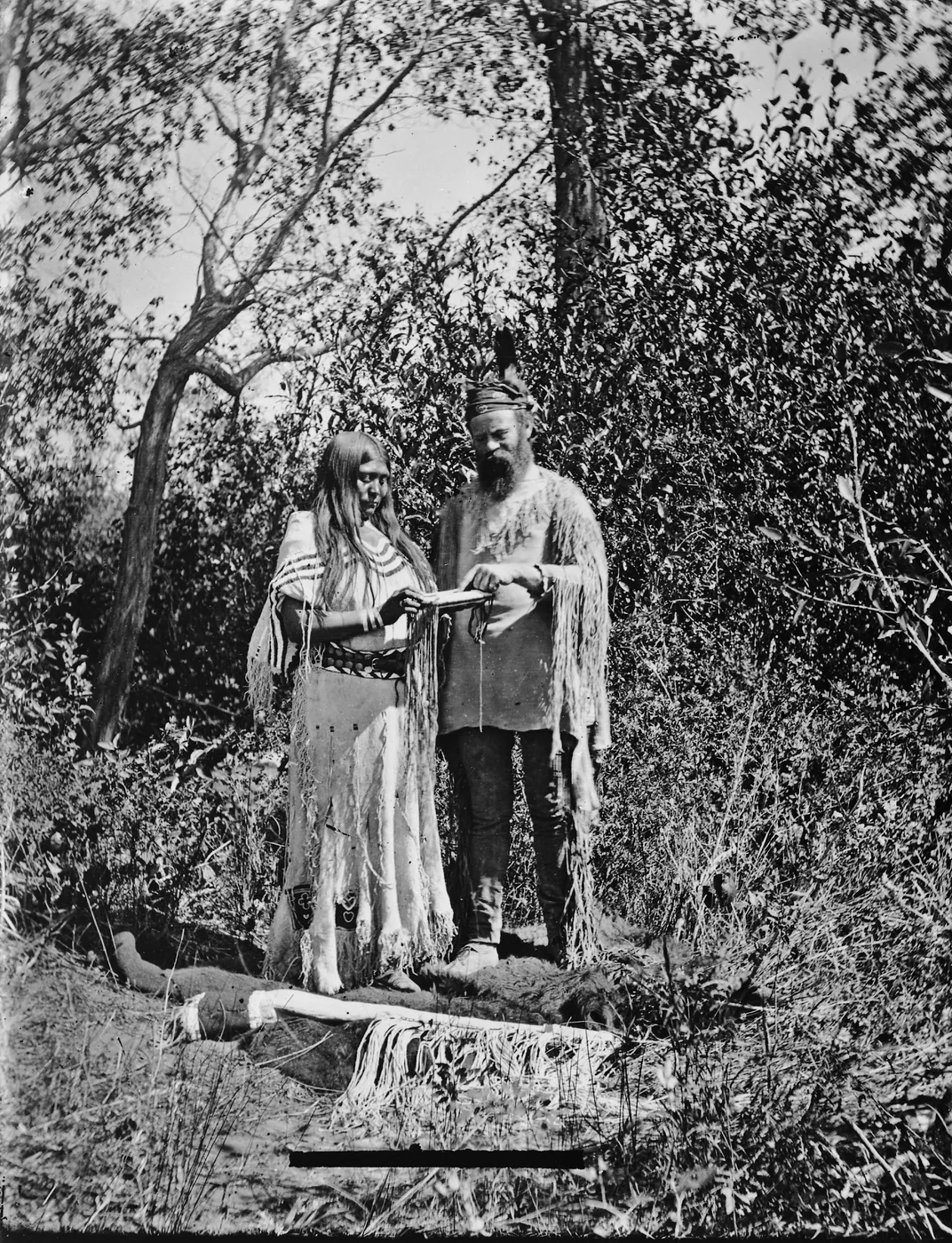

The items were collected by John Wesley Powell in the 1860s to 1880 while he was mapping and exploring the Colorado River and the Grand Canyon region. Many had appeared on Indians in photographs by Powell’s assistant Jack Hillers, who was one of the first to photographically document Native Americans, decades before the controversial but widely recognized photographer Edward S. Curtis. (Both were known to occasionally stage the Indians in activities and clothing later deemed to be inaccurate and/or historically inauthentic.)

The Smithsonian first took an interest in Powell in 1868. It was then, according to Powell biographer Donald Worster, that the Smithsonian’s first secretary Joseph Henry determined that there was both practical and scientific good to be gained from Powell’s expeditions. Henry argued in support of Powell’s request for funding from General Ulysses S. Grant, who was head of the War Department. Thus began a long relationship that would be fruitful for both Powell and the Smithsonian.

Examining the Powell collection is an exciting opportunity for the aptonymic Dove, a forensic ornithologist who runs the Feather Identification Lab and spends her time analyzing the remains of birds that have had the misfortune to fly into the path of an aircraft. She takes the blood and tissue remains—she calls it “snarge”—and using DNA, identifies the species of bird. With that information, civilian and military aircraft operations can mitigate future bird strikes with minor adjustments to avoid the birds. But Dove is also adept at identifying birds by the patterns and shapes of their feathers. Working on the Powell artifacts helps her to hone those identification skills, she says. And, it doesn’t hurt that she’s a self-identified “John Wesley Powell nut.”

Candace Greene, a Smithsonian anthropologist specializing in North American Native art and culture, and Fred Reuss, an assistant in Greene’s department at the Natural History Museum, are equally enthusiastic about what Greene calls a particularly innovative collaboration.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/ea/57eaad23-edbe-4579-93de-2c60e685adb2/_mg_8859.jpg)

It’s uncommon “to be able to revisit old collections to systematically enhance the catalog record with information on the materials used,” says Greene, noting the vast and almost incalculable size of the Institution’s collections.

The Powell collection hasn’t received a fresh investigation for decades and she and Reuss suspect that many of the earlier 19th-century identifications—including tribal affiliations and the types of animals or birds used—are simply incorrect.

The collection—which also includes baskets, seeds, weapons, tools, and other accoutrements of tribal life—has never been on display. The artifacts reside in drawers inside several dozen of the thousands of beige metal cabinets housed at the Smithsonian’s cavernous, climate-controlled Museum Support Center. A wander into the MSC’s storage area is dizzying—not just because of the rows of cabinets, known as “the pods,” that seemingly stretch to infinity, but due to the off-gassing of trace amounts of arsenic once used to preserve many museum specimens.

For scientists and Native Americans, the collection—which is available to be viewed online—offers a raft of information. Tribes can recover lost knowledge of traditional ways and their history. Biologists can use the flora and fauna to gauge climate change, environmental change and species adaptation.

The collection is also essential to the history of the Native American culture of the Great Basin (which includes the Colorado plateau) and the history of anthropology in the U.S., says Kay Fowler, emerita professor of anthropology at the University of Nevada, Reno and an expert on Great Basin cultures. “It was the founding collection for the Southwest,” says Fowler.

Powell is considered a pioneer in American anthropology, says Don Fowler, Kay’s husband, who is also emeritus at UN Reno. Noting that Powell established the Bureau of Ethnology at the Smithsonian, Fowler says, “That puts him in the premier spot, or one of the premier spots as a founder of American anthropology,” he says.

It seems astounding, but the Fowlers were the first to try to fully catalog and describe Powell’s artifacts—and that was in the late 1960s, when Don Fowler arrived at the Smithsonian as a post-doctoral researcher. Kay Fowler, who also was at the Smithsonian, recovered Powell’s manuscripts from 1867-1880 at the ethnology bureau, and the two then collated, annotated and published them in 1971. During that process, they discovered the artifacts in the attic of the National Museum of Natural History, says Don.

He and John F. Matley then catalogued the collection—to the best of their ability—in Material Culture of the Numa, published in 1979. Powell called the hundred or so tribes he encountered in the Canyon Country and Great Basin area “Numa” because their dialectics shared common roots with Numic, a branch of the Uto-Aztecan language, according to Worster, the Powell biographer.

Now, Dove, Greene, Reuss and other scientists at the Smithsonian hope to combine their expertise to bring further accuracy to the descriptions of the items in the catalog.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f4/2d/f42dfd58-e55d-41ad-9edd-2f35e8737b14/192442_1a.jpg)

The beginning of American anthropology

John Wesley Powell is perhaps best known as having been the first white man to successfully navigate the Colorado River from start to finish, mapping the river and the region, including the Grand Canyon, in the process. But there was so much more. Raised by devout Methodist immigrants from the British Isles (who named their son for church founder John Wesley), Powell wanted more than the agrarian future his parents envisioned for him.

He spent his childhood and teenage years alternating between farm life in the Midwest and pursuing an education—especially in the natural sciences. Like so many thousands of men of his age, Powell went off to war to defend the Union, losing the lower part of his arm at the Battle of Shiloh in 1862—which gave rise to his Paiute nickname Kapurats, “he who is missing an arm.” After the Civil War ended, he returned to his studies and to teaching. But a wanderlust and his passionate curiosity drove him. He could not stay put.

“In the decades following the war Powell became one of the country’s leading experts on the West—its topography, geology, and climate, as well as indigenous peoples,” writes Worster, in A River Running West, The Life of John Wesley Powell.

With U.S. government funding, Powell was among the first to document the practices, language and culture of Native Americans who lived in the Canyon Country and Great Basin areas. His acute interest in Native American culture was driven in part by the knowledge “that these cultures were threatened with extinction and were rapidly changing,” says Reuss.

But he was conflicted. Powell knew the Indians he befriended and documented “were terrified by what was happening around them,” writes Worster. “They needed a friend to help them make a transition. Powell saw himself as such a friend but one whose job it was to bring bad news where necessary and insist that the Indians accept and adapt.”

Powell was a man of his times and viewed Indians as “savages,” in need of assimilation and civilization, but his careful documentation of the languages, traditions, religious beliefs, and customs of the Paiutes, Utes, Shoshone and other area tribes was unprecedented.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a7/78/a778d894-8e82-4660-9236-2eb1fd2bab65/sia200210682web.jpg)

By the time Powell encountered the Indians in 1868, say the Fowlers, the tribes had had only intermittent contact with whites over the past century. But their cultural practices were rapidly changing. “Steel and iron began replacing chipped stone for tools; pots and pans were replacing baskets and some pottery vessels; and castoff whitemen’s clothes were being substituted for bark skirts and rabbit-skin robes,” write the Fowlers in John Wesley Powell and the Anthropology of the Canyon Country.

But Powell made sure that those artifacts and languages and customs were not completely lost. Not only did he document them, but he gathered what he could for repository. Just one meeting alone in late 1872 with several bands of Paiutes resulted in a shipment of 20 cases of material to the Smithsonian, according to Worster.

When Powell stopped collecting and went back to Washington, D.C.—which he had made his home by 1873—he did not have time to sift through and study his Native American artifacts. His western surveys and stereopticon photographs, including of the canyons and Native Americans—which he and his brother sold to the general public—had made him famous and brought him considerable renown as a scientist.

Powell was the face of the West, a man who had achieved on multiple platforms, delivering valuable topographic, geologic and hydrologic information to expansion-minded politicians. He was rewarded in Washington fashion—with a top federal post. With money from his government backers, in 1879 he began the Bureau of Ethnology. In 1881, while still running the Bureau, he took on the added responsibility of chief of the U.S. Geological Survey, which had also been established in 1879, primarily as a result of his expeditions. Powell remained director of the Bureau (later the Bureau of American Ethnology) until his death in 1902.

Feathers tell a story

By the time Don and Kay Fowler got to the Smithsonian, the Powell collection was disorganized, they say. Now, being able to draw on modern science and studies of Native culture that have been conducted since the 70s, the Smithsonian scientists should be able to improve the collection’s identifications, says Kay Fowler.

The bird feathers attached to various artifacts are of interest, as they can give anthropologists further insight into customs and trade. Feathers that might seem out of place might not be. “We tend not to think of indigenous people as trading very widely, but they did,” says Kay Fowler.

“Then there are the studies that were not envisioned by John Wesley Powell when he was collecting,” says Green, such as climate change and species adaptation.

Birds are integral to Native American culture—they are connected to the spiritual because of their ability to move throughout the earthly and heavenly (sky) realms, says Greene. Thus their feathers, attached to clothing or other items can impart particular meaning, she says. Tribal use of certain feathers can also reflect which birds were dominant in a given area.

Much was already known about the birds used in the Powell collection, but some of the artifacts had little-to-no information recorded about the bird or mammal materials employed. That led to the call to Carla Dove and the Feather Identification Lab.

Dove had an inkling of what she’d be looking at that day at the Museum Support Center, as she’d previously toured the Powell collection briefly with Greene and Reuss and made notes and took photos. When she came back, she was armed with her study specimens, like taxidermied red-tailed hawks and Swainson’s hawks and others that could validate identifications she’d made mentally, but needed to confirm with a visual feather-to-feather comparison.

She did not anticipate needing to use microscopic or DNA-based technology to come up with identifications. Sometimes, all Dove needs to see is the very tip of a feather or a disembodied beak to identify a species. But some artifacts proved to be more of a challenge.

One fringed deerskin dress was adorned on the back yoke with several bird heads, with a clutch of feathers attached to each. Using a specimen she’d brought, Dove quickly identified the heads—which had curved, pointed black beaks—as those of a particular brown-feathered woodpecker. But she was uncertain about the blue feathers, which clearly had not originally accompanied the heads. Eventually she settled on bluebird, marveling at the dressmaker’s artistic choice.

The Fowler catalog identified the dress as being made by the Goose Creek band of Shoshone, but there was nothing about the birds. “The only materials that are listed in the catalog are dressed skin and horn or hard keratin,” says Reuss. “This gives you a sense of why identifying the birds might be helpful to somebody, some future researcher, because there’s really no other data to go by,” he says.

At the end of the day, Dove and Heacker examined 45 items from the collection, charting 92 identifications. Of those, 66 identifications were corrections of what had previously been noted in the catalog. Five of the items had never been studied for bird species identifications, so those were newly added to the catalog.

Twenty-four different species of birds were included, ranging from the Western Bluebird to the Golden Eagle, says Dove. “The birds were obviously not selected at random, and it appears that eagle and hawk were preferred species, but woodpeckers and grouse were also present,” she says. “The amazing thing that I noticed when we had the items and the birds together on the table was the overall color theme—it all looked so natural with the browns, buffs and oranges.”

Greene says the collaboration has been a huge success so far. “We’ve already learned that species use is highly selective on these objects, with some types of birds favored over others,” she says. “We also see that species use is much richer than has been reported in the literature, revealing relationships between native people of the Great Basin and elements of their environment that are recorded only in these objects,” she says.

That’s fertile territory for researchers, which is why the scientists are doing so much of the leg work—to make the collections ready for anyone to start down their own avenue of inquiry. By making the collection “research ready,” it will help scientists get answers faster. “They can’t all be bird experts,” Greene says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)