A Territorial Land Grab That Pushed Native Americans to the Breaking Point

The 1809 treaty that fueled Tecumseh’s war on whites at the Battle of Tippecanoe is on view at the American Indian Museum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/3c/813c7173-9788-474d-ac5c-899106ce92e7/170919dckw107_1.jpg)

It was one treaty too far. William Henry Harrison, at the time, governor of Indiana territory (covering present-day Indiana and Illinois), had for years repeatedly squeezed Native Americans, shrinking their homelands and pushing them further west through treaties that gave little compensation for the concessions. In just five years—1803 to 1808—he had overseen 11 treaties that transferred some 30 million acres of tribal land to the United States.

But Harrison’s 1809 Treaty of Fort Wayne—which ceded about 2.5 million acres for two cents an acre—ignited a resistance movement.

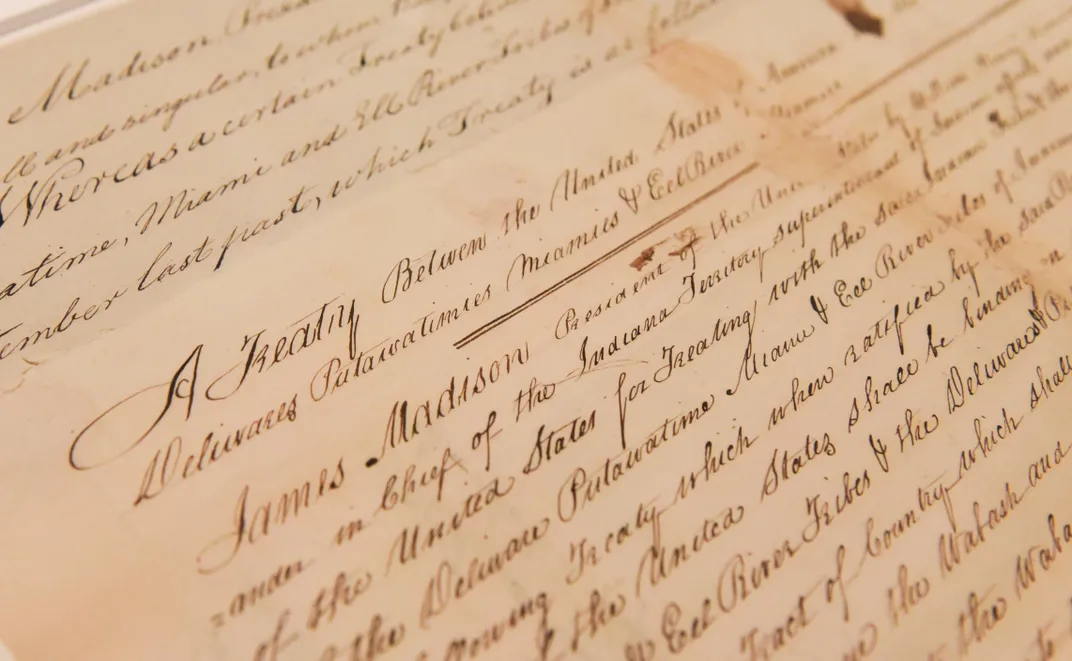

The Fort Wayne document—a somewhat ignominious piece of American history that many might want to see buried forever—has been kept in storage along with 370 other treaties at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian has brought it out for all to see and study, and reflect upon. The fragile paper is purposely under dim light and encased in a box like the one used to display the Constitution. That is “meant to show both their importance and the reverence we should have for the treaties,” says the museum’s director Kevin Gover (Pawnee).

The 1809 Fort Wayne treaty is the seventh to be displayed as part of Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations. It will be on view until January 2018.

Four tribes—Delawares, Potawatomis, Miamis and Eel River—signed the treaty, which is also known as the Treaty with the Potawatomis. But they did so with a reluctance that reverberated through the Indian nations of the region, known as the Old Northwest. Some of the Miamis said it was time to “put a stop to the encroachment of the whites,” wrote Dennis Zotigh (Kiowa/San Juan Pueblo/Santee Dakota Indian), a cultural specialist at the museum in a recent blog post.

The sense of betrayal was strong—especially among the non-signatory Shawnee, led by Tecumseh. He began staging attacks on white settlers, which escalated the response from Harrison and his armed forces. By the outbreak of the War of 1812, Tecumseh and his backers had joined with the British to help defeat the Americans.

Today’s Potawatomis have tried to come to terms with what their predecessors faced—and the 1809 treaty was just one of 40 the tribe entered into with the U.S. government.

John Warren, chairman of the Tribal Council of the Dowagiac, Michigan-based Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, and several other members of the Pokagon council attended the unveiling ceremony at the museum. For them, seeing the treaty in person was a spiritual undertaking, says Warren.

“That treaty brought up a lot of emotion in everybody today, because touching something from the past or seeing something from the past and where we are today—I thank those individuals for signing this because I think they really had the best intent of trying to make sure we survived,” he says.

“And we have survived because of the steps that they took in the best interests of the future,” Warren says.

Zotingh says, he too, felt the connection. “I can’t help but have a feeling that your ancestors are here right in this room,” Zotingh said to the assembled Potawatomis. He drummed and chanted a “Chief’s song” to commemorate the bringing of the treaty into the light.

Divide and conquer

The Fort Wayne treaty—most likely, by design—seemed to pit tribe against tribe—a typical divide and conquer strategy, says Warren.

The 2.5 million acres ceded to the U.S. cut across a large swath of present-day Michigan, Indiana, Illinois and Ohio.

The Miamis and the Delawares were given equal rights to use the White River region—as long as they consulted with each other and gave each other consent. Each tribe received the same “annuity,” a payment of $500 a year for the land they gave up. The Eel River tribe was given $250 a year, and the Potawatomi $500 a year. Another article of the treaty awarded $300 a year to the Wea tribe, whose consent was needed for the land purchase. The Kickapoo were roped in through a side treaty, and given $400 a year to sign the Fort Wayne treaty.

It’s a simple, short document, but also somewhat confusing, even in English. Warren thinks much of what was written was lost in translation—in particular because of the different languages (English and the many native tongues), and the vastly different viewpoints of the American colonizers and the Native Americans.

“This whole thing was completely foreign to native peoples,” says John Low, associate professor of comparative studies at Ohio State University, Newark, and an enrolled citizen of the Pokagon band. “The idea of land as a commodity that could be sold or held singularly, or ceded or traded away—in 1800, that was something they were still wrapping their heads around,” says Low about the Indians.

A 1915 article written by Elmore Barce, an attorney and historian, and published by Indiana University Press, describes the meetings held to hammer out the agreement and reports that the gathering quickly devolved into bickering amongst the tribes, and various demands to Harrison.

Barce's article can only be described as racist, but the descriptions of the pre-treaty council meetings and some of its other facts are corroborated by other accounts. About 1,379 members of the signatory tribes participated, while Harrison led a 14-man delegation. At times, different tribes threatened to pull out. The negotiations took two weeks, and at the end, 23 tribal leaders signed their x mark.

Low says it’s more important to look at who didn’t sign. Topinabee, the leader of the St. Joseph River area band (which later became the Pokagon band), was not a signatory. Winemek, a tribal leader, but not one of note, was the lead Potawatomi signer.

Barce claimed the treaty was negotiated in good faith and that the Indians knew what they were doing. “The articles were fully considered and signed only after due deliberation of at least a fortnight. The terms were threshed out in open council, before the largest assembly of red men ever engaged in a treaty in the western country up to that time. No undue influence, fraud or coercion was brought to bear—every attempt at violence was promptly checked by the governor—no resort was had to the evil influence of bribes or intoxicants. When agreed upon, it was executed without question,” he wrote.

A line in the sand

Tecumseh, who had been suspicious from the start, felt otherwise. To him, the Fort Wayne treaty was the line in the sand, says Low.

Even Barce acknowledges Tecumseh’s displeasure. In 1810, according to Barce, the Shawnee went to Vincennes (the capital of Indiana territory) and met with Harrison. Speaking to the Governor, Tecumseh said, "Brother, this land that was sold and the goods that were given for it were only done by a few. The treaty was afterwards brought here, and the Weas were induced to give their consent because of their small numbers. The treaty at Fort Wayne was made through the threats of Winnemac (sic); but in future we are prepared to punish those chiefs who may come forward to propose to sell the land."

It was essentially a declaration of war. Some Potawatomi, including Topinabee, and Leopold Pokagon (who later assumed leadership of the band after Topinabee’s death), allied with Tecumseh and his resistance movement, says Low.

Things came to a head in mid-1811, with Tecumseh threatening to unify tribes of the southwest to add to his northwestern tribes in his battle against the land concessions. Harrison in response mobilized 900 men and marched to Terre Haute, where in October 1811, he built Fort Harrison as a staging area for attacks on the Indians.

In November, some of Harrison’s force left the fort and camped near Tippecanoe, the village of Tecumseh and his brother The Prophet. Led by The Prophet, the Indians attacked the white men at their camp and killed or wounded a quarter of the force. But they were not able to drive them off. A day later, Harrison and his troops went to the now-deserted village—as the Indians had fled—and destroyed it. Harrison proclaimed victory at this so-called “Battle of Tippecanoe” and talked up his prowess in communiques back to Washington.

Tecumseh and his allies had not given up, however, and renewed their attacks on white settlers. When the War of 1812 began, the Indians threw in their lot with the British—an almost equally-repugnant enemy—eventually capturing Fort Detroit. Tecumseh—a wanted man—was later forced to flee to Canada, where he died in the Battle of the Thames in 1813.

Decades later, in 1841, Harrison rode his war hero status into the White House. He would die just 32 days later, making him the shortest-serving President in U.S. history.

Forgiveness, not scorn

Harrison’s suppression of Native Americans was celebrated by white culture and reviled by Tecumseh and his allies, but the tribal descendants are more forgiving of those ancestors who chose to sign the treaty.

“At that time, that was a concession to try to stay in our homeland, live our lives, and hopefully our future generations would have a good quality of life,” says Warren.

The Pokagon band was the only Potawatomi band that was allowed to stay anywhere near its original territory along the St. Joseph River in Michigan. They lost 5.2 million acres, but otherwise stayed put, says Warren.

Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations

Nation to Nation explores the promises, diplomacy, and betrayals involved in treaties and treaty making between the United States government and Native Nations.

Other Potawatomi bands—through the 1833 Treaty of Chicago—and other actions were eventually forcefully removed west. In 1838, 100 Potawatomi died on a march now known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death.

The Indians’ acceptance of treaties could be viewed as a kind of cowardice or passivity.

“I want those people to put on our shoes or our moccasins,” Warren says. “How would they feel if someone came and wanted the title to their house today? And their way of life was threatened by that. What would they do? Would they sign an agreement in the hopes that it would be honored? And give concessions of their freedom? Of the way of life that they’ve enjoyed?”

As flawed as the treaties were, they still represent a contract that Indian nations can use to hold the U.S. government accountable, says Low. “Our right to self-determination is that nation-to-nation relationship,” he says.

The treaties with Native Americans “are foundational documents in the history of the United States,” says Gover. “Without these treaties, nothing that followed would have been possible,” he says, adding that all Americans—Native and non-native—“inherit their obligations, we inherit their responsibilities, and we inherit the rights that are exchanged in these treaties.”

The obligations have never ended. “What happens next is really up to us,” Gover says.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)