The Battle in Our Backyard: Remembering Fort Stevens

Historian David C. Ward recounts the short but unprecedented Civil War attack on Washington, D.C. at the Battle of Fort Stevens on July 11, 1864

Company F, 3d Regiment Massachusetts Heavy Artillery assembled at Fort Stevens. Photo by William Morris Smith, courtesy Library of Congress.

On July 11, 1864, Lieut. Gen. Jubal Early stood contemplating the outline of the Capitol on the horizon as he prepared to launch an attack on Washington, D.C. The Confederate army had suffered a series of losses and Early was left with an exhausted but determined army looking to claim a significant victory. Remembered as the only time a president has ever been shot at in combat, The Battle of Fort Stevens is typically recalled as a small skirmish, if recalled at all. But it was a moment of panic for the Union as federal workers awaiting reinforcements were forced to arm themselves against invading troops.

The small plot of land where Fort Stevens stood is fewer than five miles from the White House, but it is easy to overlook. Historian David C. Ward of the National Portrait Gallery admits he has yet to visit. “I was looking at the map and the aerial views and it’s right down the road,” says Ward, “And I’ve never been!”

Though the two-day campaign seems inconsequential compared to other Civil War engagements, it was an electrifying shock to the Union at the time.

Abraham Lincoln’s top hat made him an easy target for Confederate sharpshooters. From the American History Museum.

“It’s a huge scare for the Union,” explains Ward. “The Union strategy had always been that you have to protect the capital and they always had a lot of troops stationed here. Lincoln and the politicians were very fearful about leaving the capital unguarded.”

Early and his troops spent the night in Silver Spring, drinking stolen wine and anticipating the next day’s events. But when morning came, so did the steamboats of veteran Union soldiers. Early’s brief window to catch the capital unprepared, armed only with a ragtag team of convalescences and panicked federal workers, had passed.

According to Thomas A. Lewis writing for Smithsonian magazine in 1988, “The citizens of Washington regained their courage. Ladies and gentlemen of society and rank declared a holiday and swarmed out to picnic and cheer the intrepid defenders.”

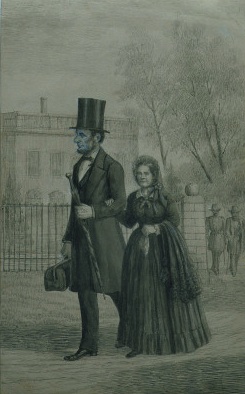

Among those watching the battle unfold firsthand were Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln.

Both Abraham, shown here with his characteristic top hat, and Mary Todd Lincoln witnessed the fighting. Drawing by Pierre Morand circa 1864, courtesy the National Portrait Gallery.

Ward describes the incredibly odd incident saying, “There’s something a little bit supernatural about the fact that, at 6’4″, Lincoln goes and stands on top of the Fort’s wall and comes under fire.” He didn’t even remove his conspicuous top hat.

“I think he feels this responsibility to see what he’s ordering other men to experience,” says Ward.

It was Union General Horatio Wright who offhandedly invited the president to get a closer look and he later wrote, “The absurdity of the idea of sending off the President under guard seemed to amuse him.”

In the end, Lincoln was unharmed and the Union won. Total numbers of those injured or killed is estimated at 874, according to the American Battlefield Protection Program.

“What would have happened if Early had been more aggressive or the Union hadn’t gotten decent troops?” Ward speculates that the Confederate troops wouldn’t have been able to hold the city but that a symbolic victory like that could have had disproportionate consequences. It would likely have cost Lincoln the election, says Ward, and, called into question the entire war.

Fort Stevens is now just a corner of grass shaded by a neighboring church. Lewis wrote after visiting the site, “I was greeted by a couple hundred feet of eroding breastworks and concrete replicas of a half-dozen gun platforms, awash in fast-food wrappers and broken glass.”

The National Park Service is currently overseeing a much-needed renovation for the battle’s approaching 150th anniversary. NPS also offers audio tours of Fort Stevens and other historic sites for download.

Learn more about the exhibits and events happening at the Smithsonian to mark the Civil War sesquicentennial, including “Mathew Brady’s Portraits of Union Generals” at the National Portrait Gallery.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)