The Eyes Have It

In the wake of the Boston bombing, Amy Henderson explores parallels between the era of Edison and the mediascape of today that helped solve the crime

![]()

Surveillance is a way of life. Photo by Quevaal, courtesy of Wikimedia

Amy Henderson, curator at the National Portrait Gallery, writes about all things pop culture. Her last post was on makeup’s greasy past.

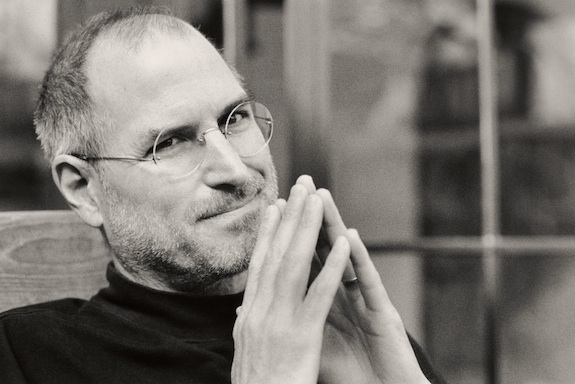

When Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone on January 7, 2007, he said, “Every once in a while a revolutionary product comes along that…changes everything….Today, Apple is going to reinvent the phone.”

The iPhone has proved even more revolutionary than Jobs understood, as its role in the remarkable capture of the Boston Marathon bombers illustrated. In the wake of the bombing, the FBI asked for crowdsourcing assistance to identify suspects. The digital sites Reddit and 4chan were instantly swamped by a “general cybervibe” of shared digital information sent from iPhones and video surveillance cameras. It was a stunning interaction between citizens and law enforcement.

This interaction is currently very high on the media radar screen. In the Washington Post, Craig Timberg recently wrote about the technologies that can produce “access to unprecedented troves of video imagery” and information about location data emitted by cellphones. In their recent book The New Digital Age: Reshaping the Future of People, Nations and Business, Google executive chairman Jared Cohen and Google director of ideas Eric Schmidt describe how a camera will “zoom in on an individual’s eye, mouth and nose, and extract a ‘feature vector’” that creates a biometric signature. This signature is what law enforcement focused on following the Boston bombing, according to Schmidt and Cohen, in an excerpt from their book, published last week in the Wall Street Journal.

Steve Jobs ushered in his own technological era. Photograph by Diana Walker, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

A media appeal from law enforcement is not new. John Walsh’s television program, “America’s Most Wanted,” is credited with capturing 1,149 fugitives between 1988 and 2011. But the stakes have sky-rocketed in the digital age, and the issue of unfiltered social media information has proved problematic. In the midst of the Boston manhunt, Alexis Madigal wrote for the Atlantic that the crowdsourcing flood revealed “well-meaning people who have not considered the moral weight” of their rush to judgment: “This is vigilantism, and it’s only the illusion that what we do online is not as significant as what we do offline. . .”

In a story on April 20th, the Associated Press reported that “Fueled by Twitter, online forums like Reddit and 4chan, smartphones, and relays of police scanners, thousands of people played armchair detectives. . . . .” The problem of inevitable mistakes, the AP noted, illustrated the unintended consequences of law enforcement “deputizing the public for help.” Reddit is a giant message board divided into subsections similar to local newspapers, except that users are the content providers. In the Boston case, users viewed their assistance as “a citizen responsibility” and engulfed the digital sites with every possible piece of “evidence.”

On the PBS News Hour April 19th, Will Oremus of Slate said that Reddit is unmediated democracy in action—a site where everyone gets to vote on what rises to the top of the page as the headlined feature. The lack of a filter means mistakes will be made, but Oremus argued that the potential for good superseded the bad. He also suggested that the Boston experience, where innocent people were momentarily tagged as suspects, illustrated how complex the learning curve is going to be.

Thomas Edison launched his own technological revolution. Thomas Alva Edison by Pach Bros. Studios, Gelatin silver print; 1907, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

It has certainly been a learning curve for me. I was intending to write here about a fascinating new book, Ernest Freeberg’s The Age of Edison, when I found myself scurrying around exploring “Reddit” and “4chan.” But as it happens, there are intriguing parallels between the advent of revolutionary technology a century ago and today’s media metamorphosis.

In the Gilded Age, Freeberg writes, society “witnessed mind-bending changes in communication. . .hardly imagined beforehand.” Their generation was the first “to live in a world shaped by perpetual invention,” and Edison personified the age with his contributions to the light bulb, the phonograph, and moving pictures.

Thomas Edison’s lightbulb. Courtesy of the American History Museum

As in the digital age today, the greatest impact then was not simply the invention itself but the invention’s consequences. There were no rules: For example, how should street lighting be constructed–should there be one giant arc light, or a series of lights lining the streets? Freeberg also explains how standards were developed for the use of electricity, and how professions evolved to implement those standards.

One of my favorite stories in The Age of Edison describes how electricity affected public behavior: people accustomed to lurching home from saloons in gaslight’s forgiving darkness were now exposed to public opprobrium by electricity’s illumination. Electricity, Freeberg suggests, was “a subtle form of social control.” Neighbors peering from behind curtains were the cultural antecedents of today’s surveillance cameras.

Like Steve Jobs did in the 21st century, Freeburg writes that “Edison invented a new style of invention.” But in both cases, what became important were the ramifications—the unintended consequences.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)