Throughout the United States and Europe, newspapers, music critics, government leaders and royal nobles raved about the captivating voice of mezzo-soprano Tsianina Redfeather. The Muscogee singer’s perfect enunciation, great vocal range, superb legato, exquisite musical intelligence, genuine presence, and overall graceful charm were the talk of every town.

Tsianina (pronounced Cha-nee-nah) Redfeather was a national superstar.

“America’s own prima donna,” as a number of century-old writings and music programs describe her: “Her general education has qualified her for university degrees, and ten years musical training under the best masters has made her one of the foremost artists America has produced and the greatest singer the Indian race has given the world,” one brochure read in the 1920s.

She was in high demand along the era’s Chautauqua circuit—a traveling commercial adult education collective that offered cultural lectures, concerts and plays from 1904 through the 1930s—touring from city to city presenting her compelling lyrics to overflowing audiences at major theaters, festivals, universities and expositions.

The promotional photograph is kind of a window into understanding how she wanted to be represented.

In 1916, Redfeather was attracting crowds of more than 7,000 in places like Kansas City. In 1918, the opera Shanewis, based loosely upon the life of Redfeather, made history as the first American opera to be revived for a second season at the Metropolitan Opera House. The show, also referred to as The Robin Woman, received 22 curtain calls after its debut.

Yet today, Redfeather’s trailblazing career is largely unknown, a narrative ripe for recovery in a month dedicated to women’s history. Helping to retell her story is a vintage promotional photograph commissioned and approved by Redfeather around 1915, and held in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

The portrait recently went on view in the museum’s 7,200-square-foot, bilingual, multimedia exhibition, “Entertainment Nation,” which traces this cultural history over a span of more than 150 years with the display of a star-studded collection of music, theater, sports, movie and television objects.

John Troutman, one of the organizing curators of the exhibition, says Redfeather’s portrait is not only a “beautiful” image, but also a rare find.

“The promotional photograph is kind of a window into understanding how she wanted to be represented,” says Troutman, who leapt at the opportunity to highlight the legacy of Redfeather in the museum, a history he first became aware of while doing research for his dissertation, which later formed the basis of his 2009 book, Indian Blues: American Indians and The Politics of Music, 1879-1934. One of his early advisors was K. Tsianina Lomawaima, an anthropologist and Redfeather’s great-niece. “Redfeather is not well known today at all. That’s really what’s kind of striking about all of this,” he says. “Like so many Native performers from her period, they were quite successful as musicians, as artists, as theatrical performers, but they were not as well chronicled and memorialized as others.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/96/da/96dac9cd-f680-44f8-8eae-1049c5bf1bc2/48607286252_7c5ce2ac87_o.jpg)

The display of rotating artifacts from the museum’s entertainment collections in the exhibition simultaneously investigates topics from Reconstruction to the displacement of Indigenous communities, as well as civil rights and immigration. “The show itself really explores how entertainment in the United States has always served as a vital forum for amplifying important conversations about who we are and want to be,” Troutman says.

Redfeather’s authenticity in presenting Indigenous culture through song and dance was one of her best qualities and personal passions, according to Troutman. She often performed with her longstanding business partner, the American composer Charles Wakefield Cadman, on stages decorated with Native items like baskets and Navajo rugs. In her 1968 autobiography, Where Trails Have Led Me, she explained that for her the spotlight became an “opportunity to tell the truth about the Indian race.”

That truth, she recalled, had a gripping effect on her fans, especially during a period of cultural misrepresentation and assimilation. “Wherever I appeared, people told me, almost with tears in their eyes, how they felt about the Indian question, how wrongly the Indian problem had been handled,” she wrote.

Redfeather, like several other Native concert performers—Haida cellist William Reddie, Pawnee tenor Paul Chilson, Yakama baritone and film actor Daniel Simmons, and Penobscot mezzo-soprano Lucy Nicolar Poolaw, also known as Princess Watahwaso—were introduced to the professional music world in the harsh era of government-enforced assimilation and allotment policies, bolstered by the ongoing prejudices and racial stereotypes that have long negatively impacted Indigenous communities.

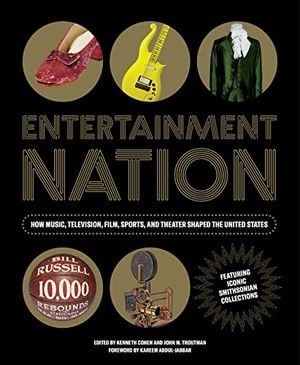

Entertainment Nation: How Music, Television, Film, Sports, and Theater Shaped the United States

U.S. history gets the star treatment with this essential guide to the Smithsonian's first permanent exhibition on pop culture, featuring objects like Muhammad Ali’s training robe, and Leonard Nimoy’s Spock ears and Dorothy’s ruby slippers.

From the mid-19th century through the 1930s, the federal government developed new policies and measures designed to “detribalize” Indigenous peoples in the U.S. by stripping them of their lands, languages and cultural traditions. While the federal government reneged on treaty promises, its Bureau of Indian Affairs worked to liquidate remaining tribal landholdings by carving up reservations in the process of “allotment.” Meanwhile, the government removed children from their families, sometimes forcibly through kidnappings, and placed them in off-reservation boarding schools, some of which were run by religious organizations. In the schools, students often were punished by school officials when caught using their Native languages or for retaining beliefs or cultural practices, including musical traditions, that were deemed a threat to the government’s goals of assimilating the children into model citizens and laborers who adhered to Anglo-Americans ideals.

One of these government-funded mission schools was where Redfeather launched her music career.

“From the Land of the Sky-Blue Water”

Born on December 13, 1882, in Indian Territory to a mixed-race Muscogee family, Redfeather from a young age was musically talented. The oldest daughter of ten siblings, Tsianina Evans (Redfeather later became her stage name) attended a federally funded Indian boarding school in Eufaula, Oklahoma, where for hours on end she practiced singing and playing the piano.

Her melodic talent grabbed the attention of one of her teachers, says her great-niece Lomawaima, a retired Arizona State University professor and longtime Indigenous studies scholar, in an interview. “That mission school was often visited by a really remarkable woman by the name of Alice Robertson, who was the first female congresswoman elected out of the state of Oklahoma, and she and the teacher kind of got together [and said], ‘This young woman has a really remarkable voice. How might we help her?’

“So they arranged for Tsianina to go to Denver, Colorado, and study with a voice coach there.”

With Robertson’s patronage, Redfeather began training with Denver’s leading vocal coach, John Wilcox. Wilcox introduced the young singer to Cadman, a composer and member of the Indianist School—a group of white composers who had a keen interest in the study of Native American culture and music—in early 1913.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/31/79/317981b0-5a2f-45cb-9c18-d20adb230168/master-pnp-ggbain-20400-20485u.jpg)

At the time, according to scholar Carter Jones Meyer, a group of white intellectuals, sympathetic to what they often described as the “plight of the American Indian,” rallied around the calling for an American musical nationalism—a specifically distinctive sound that could compete against Europe’s fine-arts scene, with its operas by Giacomo Puccini and symphonies by Antonín Dvořák. Ballad lyricist Cadman and a collective of songwriters, teachers and musicologists—including the inspiration behind the cause, ethnologist Alice Cunningham Fletcher—answered with a fresh discovery: “Indian music.”

“It’s kind of part of this early 20th-century movement to develop distinctive American arts and culture not just derived from Europeans. These were all white guys, of course, but there was a handful of them called the Indianist composers who were studying Native American music and borrowing certain rhythms, certain musical melodies,” Lomawaima says. “They were creating music that was instantly recognizable to white Americans that was high-tone music. It didn't sound really ‘Indian,’ but it was part of their musical inspiration. So Cadman is very interested in Native people and Native music.”

After successful trial performances with Cadman, Redfeather officially joined his ongoing “Indian Music Talks.” The duo accomplished a five-year run of tours throughout the U.S., stopping at schools, universities, fairs and expositions to educate concertgoers about Native culture through lecture-style performances.

According to Philip Deloria’s book Indians in Unexpected Places, the engaging program usually opened with a song by Redfeather followed by her demonstrations and interpretations of Cadman’s famous rhythms. Cadman would speak informally to the listeners while playing the piano, frequently leaving the lead of the performance to his gifted Native partner. Audiences could expect to hear heartfelt renditions of Cadman’s most famous hits, such as “From The Land of the Sky-Blue Water” and “The Moon Drops Low,” harmonized by Redfeather.

Like so many Native performers from her period, they were quite successful as musicians, as artists, as theatrical performers, but they were not as well chronicled and memorialized as others.

This unique blend of education and entertainment opened doors for Redfeather and Cadman to perform on major professional stages like the 1916 Panama-California Exposition, the Santa Fe Fiesta in 1917, and the Hollywood Bowl on June 24, 1926, where Redfeather performed the title role of Shanewis alongside the Mohawk singing star Oskenonton to a crowd of 20,000 people. She also served as an entertainer as part of the American Expeditionary Forces overseas in World War I.

Everywhere she stepped foot, audiences were captivated by her talent and excited to learn about America’s burgeoning individual sound.

“Tsianina sings with rare candor and expressiveness; one of the most brilliant musical events in the history of the festival,” wrote one reviewer in the 1920s.

The public was as intrigued by Redfeather’s stage persona as by her musical ability.

A Colorado State Teachers College publication boasted in 1915: “Appearing with Mr. Cadman is the Princess Tsianina Redfeather. She is a full-blooded Indian aristocrat, descendant of the famous old Chief Tecumseh. The personality that has been so much admired on the platform is not assumed for the public occasion—it is her real personality.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2d/c5/2dc5e6d7-a93e-47e5-84e4-372a7ba815f2/master-pnp-ggbain-30300-30381u.jpg)

Redfeather often performed and was often photographed in what Western culture expected as the Native signature style for women: a fringe buckskin dress, moccasins, a beaded headband and beaded jewelry.

In an interview, Deloria explains these idealized outfits and elaborate stories of royal heritage were a way to play upon—and at times fit into—Western expectations.

“In the early 20th century, there’s a way non-Native audiences are willing to see Indians, and there are ways in which they’re not willing to see Indians. So it’s a kind of ideological play,” Deloria says. “They’re willing to see Indians as modern people, right? Wearing a tuxedo, for example, or concert clothing, as long as they can also see them as kind of ‘primitives.’ This naming of women as princesses, men as chiefs, it’s very common, so these are just ways of making Native performers culturally legible to non-Native audiences. Performers are willing to embrace some of those stereotypes as a way to make a living, and to speak to non-Native audiences.”

Redfeather was aware of her stage presence and what it meant to white audiences. Her experiences on tour led her to reach a deep appreciation for her own identity.

“The people’s response to Indian music [when I was touring] gave me a love for my country and for being a Native American that I had not felt as strongly before,” Redfeather explains in her book. “I was now a part of my song, a part of my heartbeat, and I knew where I was going.”

Redfeather strove to correct misrepresentations and appropriations of Indian culture in music, film and TV. The versatile artist made it a point to perform for the Native reform organization Society of American Indians, and she served on an Indian affairs advisory council, remaining active in the organization even after retirement in 1935.

As her career slowed, she took up residence in Chicago for a while and founded the First Daughters of America, a federation of Native American women.

Tsianina sings with rare candor and expressiveness.

“I want the American people to know the Indian as he is and has been, and not as he has been so grossly misrepresented to be,” Redfeather wrote in a newspaper article. “Indian traditions and traits of character have been monstrously defamed. The popular conception seems to be drawn largely from motion picture characterization. I feel in justice to my people that I should do all in my power to dispel these illusions.”

Redfeather in her later years became a devout member of the Christian Science Church, and resided in Burbank, California, according to Lomawaima. Around 1930, she married Arthur Blackstone. A previous marriage a decade earlier to David F. Balz had ended in divorce. The second marriage lasted just three years, but she continued to use the name Blackstone until her death at age 102 in 1985.

With the rise of jazz music in the U.S. during the Roaring Twenties, the hardships of the Great Depression and the emergence of World War II, the popularity of Indian-themed music as performed by Redfeather, Cadman and others began to fade.

Exhibitions like “Entertainment Nation” serve a key role in shining a light on people who have been overlooked throughout history, Lomawaima says.

“I think it was really important that Native people were on the public stage to the degree they were at that period of time,” she says. “But sadly, all that really disappears with the Depression and World War II, and the American fascination with certain aspects of Indian life disappears. It’s why so many of those performers, including Tsianina by the 1960s, ’70s, ’80s, are completely unknown. All that history has just been erased.

“Entertainment Nation / Nación del Espectáculo” is on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/15/f5/15f5eade-e29c-4c0d-968c-726fbdcf00b1/tsianina-redfeather.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Briana_T._headshot_1_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Briana_T._headshot_1_thumbnail.png)