The Man Who Viewed the Bible as Art

The Washington Codex, now on display at the Freer gallery, became one of the earliest chapters in Charles Freer’s appreciation of beauty and aesthetics

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20131125103040around-the-mall-freer-bible-room-thumb.png)

It’s not the place you would expect to find the world’s third-oldest manuscript of the gospels. The jade-like walls of the Freer Gallery’s Peacock Room are beautifully rendered in rich detail work. Delicate spirals rim the panels and gold-painted shelves line the walls, housing dozens of works of Asian ceramics. On one end, a woman immortalized in portrait, robe falling from her shoulders, watches over the room. To her left, a row of closed shutters block the room’s access to the sunlight. Golden peacocks, their feathers and tails painted in intricate detail, cover the shutters. On the far wall, two more peacocks are poised in an angry standoff. One is dripping with golden coins. The creature is a caricature of the Peacock Room’s original owner, the wealthy Englishman Frederick R. Leyland. The other peacock represents the struggling, underpaid artist—James McNeill Whistler. Whistler, who fought with Leyland, his patron, dubbed the piece “Art and Money; or, the Story of the Room.”

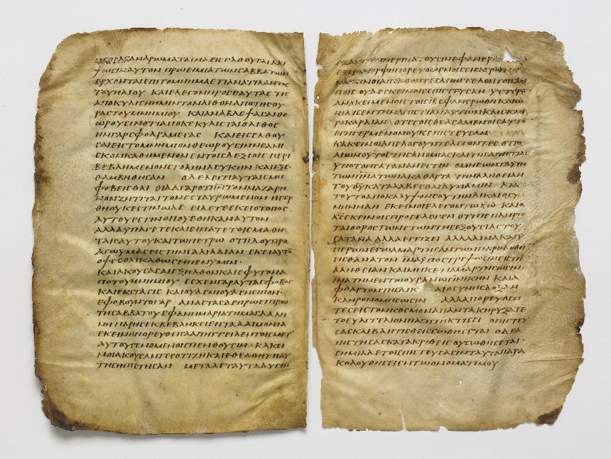

The parchment pages of the late 4th to 6th century biblical manuscripts, recently placed on view in the middle of the room, were originally intended to be handled and turned gently, most likely, as a part of the liturgy, by the monks that owned and read them. In the seventh century, wooden covers painted with the figures of the four Evangelists were added, binding the manuscript tightly and making the pages much harder to turn. At that time, the bound books probably made the transition to a venerated object—but yet not a work of art.

The man who saw them as works of art was Charles Lang Freer, who purchased the manuscripts from an Egyptian antiques dealer in 1906 for the princely sum of 1,800 pounds, about $7,500 in today’s dollars. In 1912, after having purchased the Peacock Room in London and shipping it to his Detroit home, Freer set out the manuscripts in the room, displaying them for his guests, along with his collection of pottery and various Buddhist statues.

“Freer had this idea that even though all of the objects in his collection were quite diverse from all different times and places, they were linked together in a common narrative of beauty that reached back in time and came forward all the way to the present,” says curator Lee Glazer. “By putting the bibles in this setting which is a work of art in its own right, with all of these diverse ceramics, it was kind of a demonstration of this idea that all works of art go together, that there’s this kind of harmony that links past and present and East and West.”

Covers of Washington Manuscript III: The Four Gospels. Encaustic painting. Photo courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art.

The Freer Gallery chose to exhibit the manuscripts—their first public showing since 2006—much as the museum’s founder first did in 1912, focusing on their value as aesthetic objects and their juxtaposition against the opulence of the Peacock Room.

“This display of the bibles is less about the bibles as bibles than the surprising fact that he chose to exhibit them in the Peacock Room as aesthetic objects among other aesthetic objects,” explains Glazer.

The bibles are the first antique manuscripts that Freer bought, and while he purchased a few other rare texts in his lifetime, he never really threw himself into collecting them with the same fervor that he applied to his pottery collection. To Freer, the manuscripts were an important chapter to include in his collection at the Smithsonian—another chapter in the history of beauty throughout the ages.

The Freer bibles on display in the Peacock Room, with “Art and Money” in the background. Image courtesy of the Freer Gallery.

Not everyone agreed with Freer’s presentation of the rare texts, however. “In one of the newspaper clippings, they accuse Freer of being too fastidious in the way that he’s treating the bibles,” Glazer says. “They suggested that they shouldn’t be considered works of art as objects, but as holy scripture.”

To Freer, the manuscripts represented an ancient chapter in the history of beauty, but he also understood their historical significance for biblical study. Upon his return to America, Freer underwrote $30,000 to support research conducted by the University of Michigan. In translating and studying the texts, the scholars found that one of the gospels contains a passage not found in any other biblical text. The segment, located at the end of the Gospel of Mark, includes a post-resurrection appearance of Christ before his disciples where he proclaims the reign of Satan to be over. For some, this revelation was more scandalous than Freer’s decision to showcase the manuscripts as aesthetic objects.

“It’s not found in any other known version of the gospels,” explains Glazer. “The fact that it said that the reign of Satan was over seemed really potentially outrageous. People were in a tizzy over it.”

The manuscripts, normally kept in the Freer Gallery archives due to their sensitivity to light, are some of the most sought after pieces in the gallery’s collection. The manuscripts will remain on display in the Peacock Room through February 2014.