A huge, excited crowd packed Booth’s Theatre. On Manhattan’s sidewalks, Broadway fans jostled each other, gathering to mark Charlotte Cushman’s 1874 New York retirement after a four-decade stage career in which she had tackled some of Shakespeare’s most iconic roles—both male and female. Inside the theater, politicians, socialites and captains of industry were the privileged witnesses of her final performance. After the show, a candlelit procession accompanied the accomplished actor to the Fifth Avenue Hotel, where fireworks and a choir of singers celebrated her success. Similar festivities followed in Boston and Philadelphia, where she also told her fans goodbye.

“She was one of the most, if not the most, famous women in the English-speaking world during her lifetime,” says Lisa Merrill, author of the 1999 When Romeo Was a Woman: Charlotte Cushman and Her Circle of Female Spectators.

Hers was a fame so candescent that Cushman’s social circles included world leaders from President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward to Queen Victoria, and American literary lights from Nathaniel Hawthorne and Walt Whitman to Louisa May Alcott. When she returned to the United States after years regaling European audiences, American newspapers hailed her, says Merrill, as the cultural icon of the era, “Our Charlotte,”—a name so well-known that like today’s Madonna, for decades she needed no last name.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/28/9f/289f7940-c948-402f-85cd-f3250cb23b26/cushman_sister_litograph.jpg)

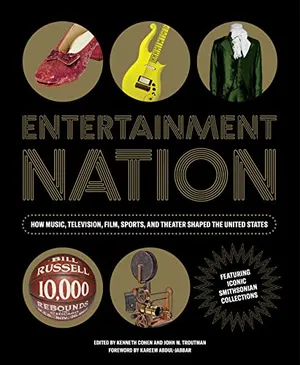

Entertainment Nation: How Music, Television, Film, Sports, and Theater Shaped the United States

Entertainment Nation is a star-studded and richly illustrated book celebrating the best of 150 years of American pop culture. The book presents nearly 300 breathtaking Smithsonian objects from the first long-term exhibition on popular culture, and features contributors like Billie Jean King, Ali Wong, and Jill Lepore.

Yet today, her story goes largely forgotten. Stage performances are naturally ephemeral, but Merrill believes that following her death in 1876 after a long battle with breast cancer, the onetime star’s fame declined, primarily because of her sex life. “The attempts to erase her or render her merely unusual, ‘odd,’ or inconsequential have not been accidental; each largely reflects the attitudes toward gender and sexuality at the time the accounts were written, rather than attempts to locate the significance of such attitudes in her time,” Merrill wrote.

Those attitudes form a lens on the life of a woman who loved other women. Throughout her career in the late 19th century, she was cast as an admirable virgin who remained chaste by avoiding men.

In the decades following her death at 59, she was stigmatized for her long-term relationships and shorter dalliances with other women. Early 20th-century writers, who failed to identify her as a lesbian, sometimes described her as strangely mannish, asexual—and odd. However, in recent decades Cushman’s life story is re-emerging from the shadows. Biographer Tana Wojczuk’s 2020 book Lady Romeo: The Radical and Revolutionary Life of Charlotte Cushman, America’s First Celebrity has met with critical praise for reviving the actor’s “force and vitality.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/1a/57/1a57037f-f154-425a-9651-a59cf00699a8/charlotte_cushman_costume.jpg)

At the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, a costume Cushman wore—the oldest in the museum’s collections—in 19th-century productions of Shakespeare’s Henry VIII will go on display in the upcoming “Entertainment Nation". The 7,200 square-foot exhibition offers a deep dive into the museum’s popular culture holdings and explores the impact of music, theater, film, sports and television on American life for more than 150 years.

The costume helped Cushman morph into a male character—Cardinal Wolsey. In the same play, she sometimes portrayed Katharine of Aragon, and a gown made for that character resides in the museum as well. At times, Cushman alternated between these two roles on consecutive nights. The museum also holds a Cushman shawl, which she probably donned for one of her most famous portrayals—a fierce Lady Macbeth, whom she brought to life in both her first and last starring roles.

The Cardinal Wolsey costume was first loaned to the museum in 1914 and was studied not for its association with Cushman but oddly as an example of what 16th-century clothing looked like. For the upcoming exhibition, Kenneth Cohen, who worked at the museum for two years while simultaneously heading the museum studies program at the University of Delaware, researched the garb, uncovering new details about its history. “The costume includes actual 16th-century Milanese lace that she acquired in Italy,” he says. In 1857, she had the bright red apparel made to order in London.

Cohen determined that it was the museum’s oldest costume by finding a tiny maker’s mark in one slipper. The ensemble features a long trainlike cape, “and there are all kinds of tears on the underside of the cape from when she accidentally stepped on it backstage or onstage,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/be/dc/bedc3c97-fc6a-4644-ab41-31131648fdcf/cushman_dress.jpg)

"Flickering candlelight is playing off these colored-glass faux gemstones. And you can imagine the visual spectacle.”

The gown made for Cushman’s portrayal of Katharine of Aragon was sewn with many embroidered faux gems. “Imagine, in that period, the lighting is all by candlelight, more or less … and so the flickering candlelight is playing off these colored-glass faux gemstones. And you can imagine the visual spectacle of wearing that gown,” says Cohen.

Although other women portrayed men onstage in what were called “breeches roles,” Cushman’s performances were different. Most women used the gender switch as an excuse to show off their legs in tight pants—a sexy nod to the audience—while Cushman seriously embodied male characters, including Romeo and Hamlet. Her costumes, which were increasingly well-made as her career soared, matched the sober all-encompassing nature of her performances.

Onstage in the role of a male character, Cushman delivered different messages to members of the audience. “To men, she embodied the man they wanted to be, gallant, passionate, an excellent sword-fighter,” wrote Wojczuk. “To women, she was a romantic, daring figure, their Romeo.” An anonymous female Romeo fan wrote: “Charlotte Cushman is a very dangerous young man.”

Wojczuk makes the argument that Cushman’s performances liberated men, in a way. “When she wept over her Juliet’s death as Romeo, it gave men in the audience license to do the same,” she wrote. “She helped expand the definition of masculinity as well as femininity.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c4/4d/c44d976f-d206-48c1-9d07-cfb397626d19/charlotte_cushman_sully_1843.jpeg)

Cushman sometimes dressed in men’s clothing offstage as well. She was seen as androgynous, Merrill says. However, because there was no discussion of transgender identities at that time, Merrill argues, it is impossible to retroactively categorize her using today’s terminology.

Cushman was born into a financially comfortable family. Her mother’s family traced its heritage to a passenger on the Mayflower. When the would-be actress was 13, her father’s business failed, and he disappeared. Consequently, she left school to support her family. Initially, she performed menial labor. She began her onstage career with hopes of becoming an opera star but lost her voice and started to fill bit parts in melodramas and Shakespearean plays. Sometimes, she used her acting talent and understanding of the theater to earn money in different ways, as she did as manager of Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Theatre in the early 1840s. Away from the theater, Cushman augmented her income by writing poems and short stories that appeared in Godey’s Lady’s Book and the Ladies’ Companion.

After finding some success on the stage in the U.S., the moment arrived to prove herself as an actress. She boarded a ship for London to face audiences and critics who were skeptical about the work of American actors. Within a year, her accomplishments had begun to give her an international reputation. Cushman encouraged her sister, Susan, to become an actress as well and to play Juliet alongside Charlotte’s Romeo, starting in December 1845 on the London stage. The unconventional idea of two sisters in these romantic roles attracted large audiences. Queen Victoria, who saw them take on the classic roles, thought Charlotte “entered well into the character” of Romeo and did not seem at all like the young woman she was. Early in her career, Cushman faced criticism for being too tall—5-foot-6—and for a lack of beauty, but as she embraced breeches roles, her appearance supported her dramatic work. In addition to insisting on the casting of her sister, Cushman demanded that the production follow Shakespeare’s original text rather than a then-popular plot-changing rewrite that had Juliet awaken before Romeo died. As a theatrical artist, Cushman carried significant influence. She was a powerful force, choosing her roles carefully and making important decisions on scripts, costumes and co-stars. Once she had risen to stardom, she demanded pay that was equal to what her male counterparts received.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8f/ba/8fba8d32-519d-40dd-9e87-6b526708e16d/gettyimages-1410628248resized.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a6/04/a6041e99-fcb0-459e-b2e4-2e34cd2cc5d4/gettyimages-1277840722.jpg)

Following her triumph in London, Cushman found eager audiences when she returned to the U.S. She became wealthy as her fame spread and soon could take time away from the theater to enjoy a privileged life.

In the 1850s, she joined other female artists to form a household in Rome. There, Cushman attempted to bolster the careers of young women, such as the American sculptor Edmonia Lewis, who had a Black father and a Native American mother. In Rome, Cushman’s home life became what has been described as “a group of highly mobile, independent women [who] began enjoying an international transatlantic lifestyle that now seems strikingly modern.” However, at the time of the household’s founding, some men wrote critically about what they viewed as its unnatural composition.

While she often lived as an expat, Cushman performed frequently in the U.S., including several fundraising appearances during the Civil War to support the Union cause. Americans took pride in her international success. Several U.S. cities hosted Cushman Clubs, which offered locations for the safe accommodations of out-of-town female actresses.

Throughout most of her life, Cushman shared her home with a lover, typically described as a friend by the press. In the 19th century, many public attitudes about sex arose from the belief that women drew no sexual pleasure from their libidos. That belief made “romantic friendships” with other women seem to be a natural part of a chaste woman’s life, providing an opportunity for spiritual intimacy without the complications built into male-female unions. Cushman made the most of these misconceptions. Public blindness to her relationships also probably helped her to hide infidelities from her lovers. Even in an environment that seemed to guard her secrets, Cushman urged the women she loved to destroy each love letter when a new one arrived.

After her death, the New York Times wrote that “it is worth something to have seen and heard an actress like Charlotte Cushman, whose genius was thoroughly informed by an intelligent purpose, and whose inspiration was always supported by the fruits of years of assiduous toil and study.”

On the night of her final performance, Cushman described what had driven her career: “Art is an absolute mistress; she will not be coquetted with or slighted; she requires the most entire self-devotion, and she repays with grand triumphs.” In that era, her art, not her sexual orientation, was most noteworthy.

“Entertainment Nation” goes on view at the National Museum of American History beginning December 9, 2022.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(800x701:801x702)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5f/46/5f46a58b-e4ac-4d1d-aa08-2c84ffad7eba/npg-npg_72_15altered.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)