The Story Behind Smithsonian Castle’s Red Sandstone

Author Garrett Peck talks about uncovering the stone’s history for his new book, The Smithsonian Castle and the Seneca Quarry

![]()

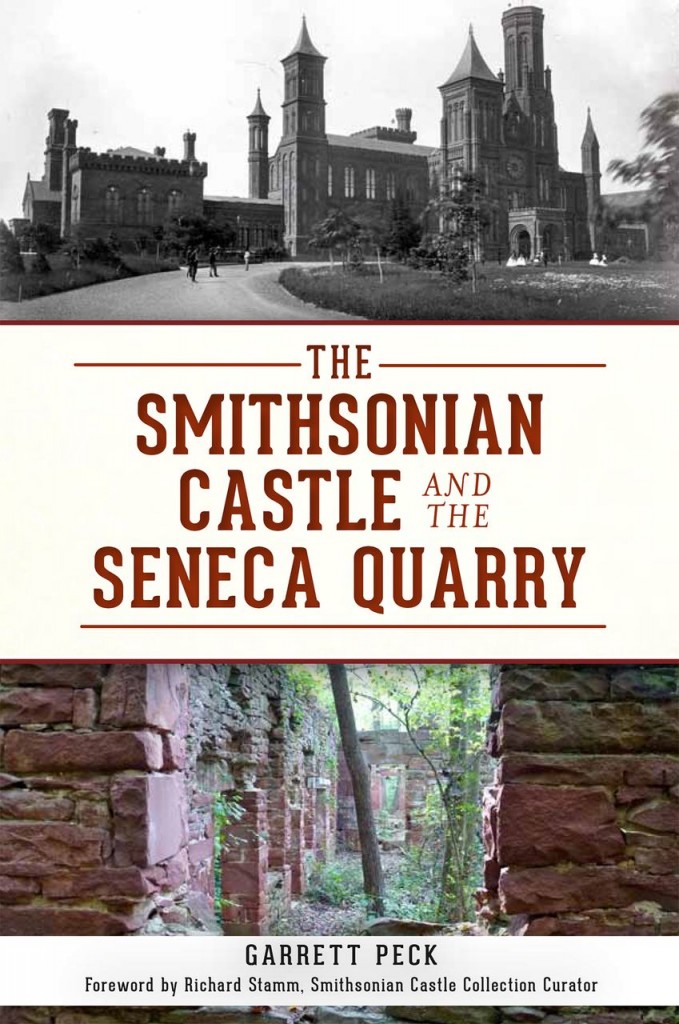

The Smithsonian Castle was built in the 1850s, using the red sandstone from the Seneca quarry. Author Garrett Peck tells the quarry’s story in his new book, The Smithsonian Castle and the Seneca Quarry. Photo courtesy of Garrett Peck

The red sandstone façade of the Smithsonian Castle makes it one of the most striking buildings in Washington, DC. The stone for the building was cut less than 30 miles away at the Seneca Quarry along the Potomac River in Maryland and shipped to the city in the 1850s when the building was first under construction. But the quarry’s story is a complicated one, involving death, floods, bankruptcy and presidential embarrassment. DC author and historian Garrett Peck recently set about telling its tales in his new book, The Smithsonian Castle and the Seneca Quarry, out now via The History Press. We chatted with Peck via e-mail about the Castle’s construction, the importance of preserving the stone’s history and the quarry’s “boom-bust ride” of fortune and ruin.

What makes Seneca redstone so special?

Seneca redstone is unique for its color and durability. It is a rusty red color, caused by iron oxide that leached into the sandstone (yes, it literally rusted the stone). The stone was easy to carve from the cliffs near Seneca Creek, Maryland, but it hardened over the course of a year, making it a durable building material. Thus you see Seneca redstone in hundreds of 19th-century buildings around Washington, especially around the basement levels. The stone was considered waterproof.

Why was Seneca redstone chosen for the Castle?

Fifteen quarries from across the Mid-Atlantic bid on the Smithsonian Castle project in 1846, and the Castle could have ended up any number of different colors: granite, marble, white or yellow sandstone—or redstone. The Seneca quarry owner, John P.C. Peter, underbid the competition by such a staggering amount that it drew the attention of the Castle’s Building Committee. It was almost too good to be true, so they dispatched architect James Renwick and geologist David Dale Owen to investigate. They returned with good news: there was more than enough stone to build the Castle. Renwick wrote the Building Committee: “The stone is of excellent quality, of even color, being of a warm gray, a lilac tint resembling that known as ashes of rose, and can, from all indications, be found in sufficient quantities to supply all the face work for the Institution.”

What was the Seneca Quarry like at the height of its production?

The Seneca quarry must have been a bustling and noisy place to work, what with the constant hammering away at the cliffside, the din of workers carving and polishing the stone, and the braying of mules who pulled the C&O Canal boats to Washington. We don’t know how much redstone was removed, but it was extensive: there were about a dozen quarries stretching along the one-mile stretch of the Potomac River west of Seneca Creek. The workforce included many immigrants from England, Ireland and Wales, as well as African Americans. Slaves most likely worked at the quarry before the Civil War—and freedmen certainly worked there until the quarry closed in 1901.

Your book says the quarry’s history was a “boom-bust ride.” What was some of the drama surrounding the quarry and the Castle’s construction?

The Seneca quarry had four different owners: the Peter family, who owned it from 1781 to 1866, then sold it after their fortunes declined because of the Civil War. Three different companies then owned the quarry until it closed—two of them going bankrupt. The Seneca Sandstone Company (1866-1876) was horribly managed financially. It was involved in a national scandal that embarrassed the Ulysses S. Grant presidency and helped bring down the Freedman’s Bank. The quarry’s last owner shut down operations in 1901 once it became clear that redstone was no longer in fashion. It had had a good five decade run while Victorian architecture reigned.

What is the Seneca quarry like today?

The Seneca quarry sits right along the C&O Canal about 20 miles upriver from Washington, DC in Montgomery County, Maryland. But it’s so overgrown with trees and brush that most people have no idea that it exists—even though hundreds of people bike or walk right past it everyday along the canal towpath. Luckily the land is entirely protected in parkland, so it can never be developed. I have a dream that we can create a visitor park in the quarry so people can explore its history year-round.

We so rarely ever make the connection between our building materials and the places where we live and work. Yet every brick, sheetrock, splotch of paint and wooden doorway came from somewhere, didn’t it? The Seneca quarry is one of those forgotten places—but fortunately it isn’t lost to us.

What is your personal connection to the story of Seneca Quarry?

I discovered the Seneca quarry while researching my previous book, The Potomac River: A History and Guide. It was the one major historical site that I found along the Potomac that no one knows about—there isn’t so much as a sign to indicate that it’s there. It is such a fascinating site, like discovering something lost from ancient Rome (even though it only closed in 1901). There has never been a book about the quarry’s history written before, and I also soon discovered that there were no quarry records. It was a story that I had to piece together by searching through archives. Happily I found a treasure trove of historic photos showing the Seneca quarry in action—many populated with the African American workers who worked there.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/paul-bisceglio-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/paul-bisceglio-240.jpg)