The Uncertain Promise of Freedom’s Light: Black Soldiers in The Civil War

Sometimes treated as curiosities at the time, black men and women fighting for the Union and organizing for change altered the course of history

![]()

Martin Robinson Delany worked to recruit soldiers for black Union regiments and met with Lincoln to allow these units to be led by black officers. He approved the plan and Delany became the first black major to receive a field command. Hand-colored lithograph, 1865. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

Black soldiers could not officially join the Union army until the Emancipation Proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863. But, on the ground, they had been fighting and dying from the beginning.

When three escaped slaves arrived at Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia, in May, 1861, Union General Benjamin Butler had to make a choice. Under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, he was compelled to return the men into the hands of the slaveowner. But Virginia had just signed the ordinances of secession. Butler determined that he was now operating in a foreign territory and declared the men “contraband of war.”

When more enslaved men, women and children arrived at the fort, Butler wrote to Washington for advice. In these early days of the Civil War, Lincoln avoided the issue of emancipation entirely. A member of his cabinet suggested Butler simply keep the people he found useful and return the rest. Butler replied, “So should I keep the mother and send back the child?” Washington left it up to him, and he decided to keep all of the 500 enslaved individuals who found their way to his fort.

“This was the beginning of an informal arrangement that enabled the union to protect fugitive slaves but without addressing the issue of emancipation,” says Ann Shumard, senior curator of photographs at the National Portrait and the curator behind the new exhibit opening February 1, “Bound For Freedom’s Light: African Americans and the Civil War.”

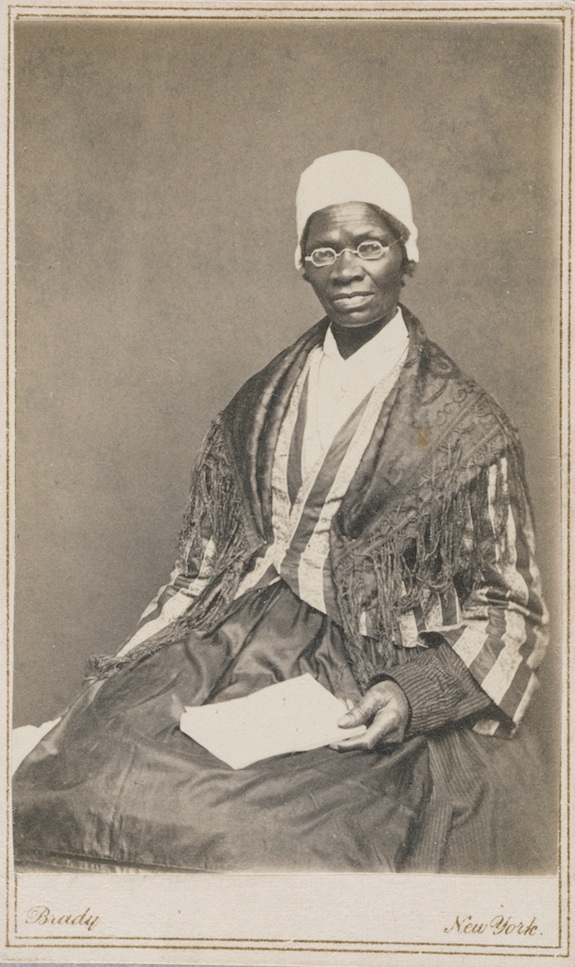

An abolitionist and former slave, Sojourner Truth also helped recruit soldiers in Michigan. Mathew Brady Studio, albumen silver print, circa 1864. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

Though many know of the actions and names of people like Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth, hundreds of names have been more or less lost to history. Individuals like those who made the dangerous journey to Fort Monroe tell a very different story of the Civil War than usually rehearsed.

“They were very much active agents of their own emancipation in many instances and strong advocates for the right to participate in military operations,” says Shumard, who gathered 20 carte de visite portraits, newspaper illustrations, recruitment posters and more to tell this story.

Amid the stories of bravery both inside and outside of the military, though, rests a foreboding uncertainty. There are reminders throughout the exhibit that freedom was not necessarily what waited on the other side of the Union lines.

“There were no guarantees that permanent liberty would be the outcome,” says Shumard. Even grand gestures like the Emancipation Proclamation often fell flat in the daily lives of blacks in the South. “It didn’t really free anybody,” says Shumard. The Confederates, of course, did not recognize its legitimacy. All it truly ensured was that blacks could now fight in a war in which they were already inextricably involved.

Events like the July, 1863 draft riot in New York City, represented in the exhibit with a page of illustrations published in Harper’s Weekly, served as a reminder that, “New York was by no means a bastion of Northern support.” According to Shumard, “There was a strong amount of sympathy for the Confederacy.” Though the five-day riot began in protest against the unequal draft lottery policies that would allow wealthy people to simply pay their way out of service, anger quickly turned against the city’s freed black population. “No one was safe,” says Shumard. Shown in the illustrations, one black man was dragged into the street, beaten senseless and then hanged from a tree and burned before the crowd.

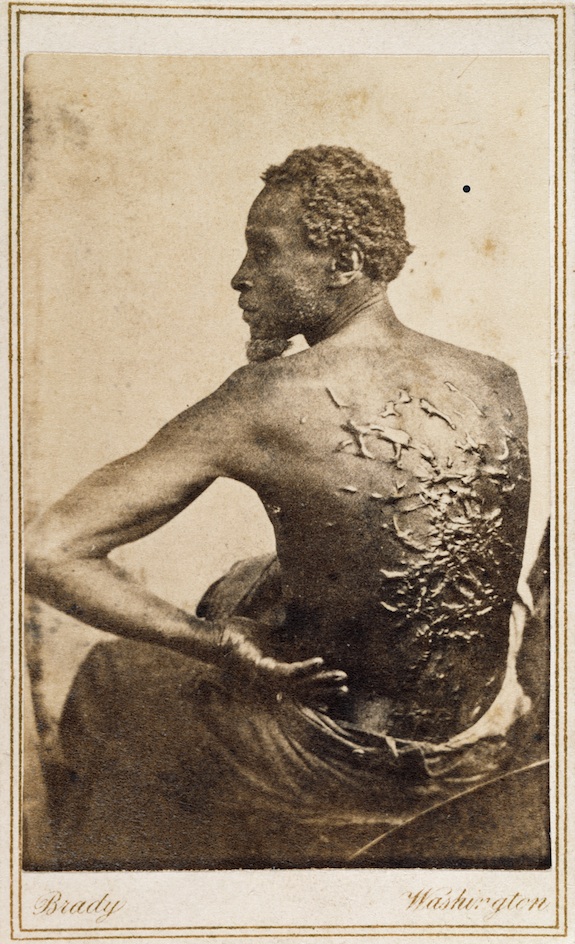

After escaping slavery on a Louisiana plantation, Gordon reached Union lines in Baton Rouge where doctors examined the horrific scarring on his back left from the whipping of his former overseer. Photographs of his back were published in Harper’s Weekly and served to refute the myth that slavery was a benign institution. Mathew Brady Studio albumen silver print, 1863. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

Joining the Union cause was also an uncertain prospect. Before the emancipation proclamation, it was unclear what might happen to escaped slaves at the end of the war. One suggestion, according to Shumard, was to sell them back to Southern slaveowners to pay for the war.

“There were times when one might have thought that the outcome of a battle or something else would have discouraged enlistment when in fact it actually only made individuals more eager to fight,” Shumard says.

Meanwhile, black soldiers had to find their place in a white army. Officers from an early Louisiana guard of black troops organized by Butler, for instance, were demoted because white officers “objected to having to salute or otherwise recognize black peers.”

Frederick Douglass encouraged service nonetheless, calling on individuals “to claim their rightful place as citizens of the United States.”

Many did, and many, in fact, had already.

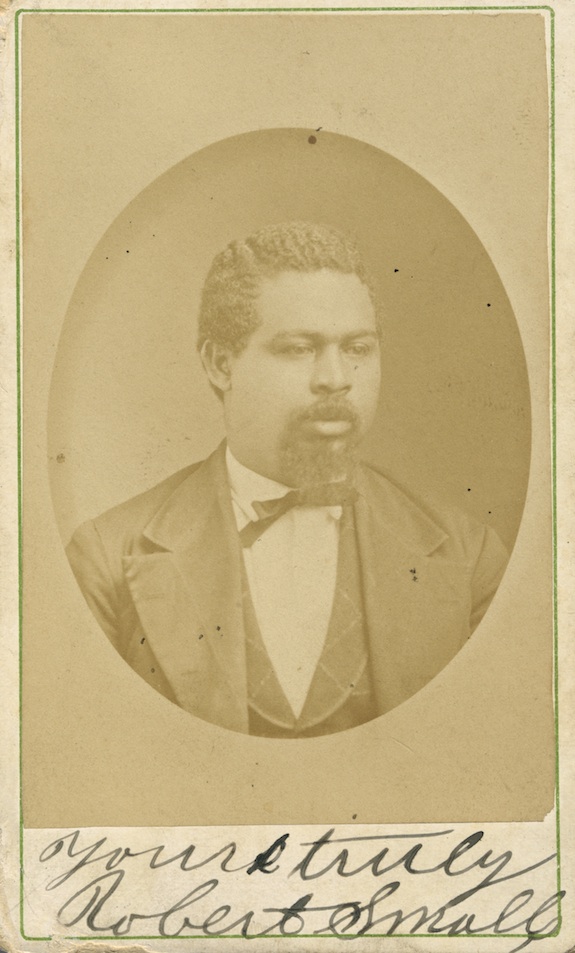

After his time in the Union army, Smalls went on to serve in South Carolina politics during Reconstruction. Wearn & Hix Studio albumen silver print, 1868. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

A celebrated tale at the time, the story of deckhand Robert Smalls’ escape from the Confederates inspired the North. Smalls had been sent away as a young child in South Carolina to earn wages to send back to his slave master. By 1861, he was working on a Confederate ship. With his shipmates, he plotted to commandeer the vessel while the white crew was ashore. Before the sun rose one morning in May, 1862, the group set to work, navigating their way toward Union lines. Disguised with the captain’s straw hat and comfortable moving around the fortifications and submerged mines, Smalls made his way to safety and went on to pilot the same boat for the Union army. Shumard says, “There was great rejoicing in the North at this daring escape because he had not only escaped with his shipmates, but they had also picked up members of their families on the way out.”

But often these stories were treated with derision by the popular press, as in the instance of a man known simply as Abraham who was said to have been literally “blown to freedom.” As a slave working for the Confederate army, Abraham was reportedly blasted across enemy lines when Union soldiers detonated explosives beneath the Confederate’s earthen fortifications.

“The Harper’s Weekly article that was published after this happened tended to treat the whole episode as a humorous moment,” says Shumard. “You find that often in the mainstream coverage of incidents with African American troops, that it can sometimes devolve almost into minstrelsy. They asked him how far he had traveled and he was quoted as saying, about three miles.”

Abraham stayed with the Union troops as a cook for General McPherson.

“By the end of the Civil War, roughly 179,000 black men (10 percent of the Union Army) served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 19,000 served in the Navy,” according to the National Archives. “Nearly 40,000 black soldiers died over the course of the war—30,000 of infection or disease.”

Posed near the final print of the exhibit showing a triumphant Lincoln striding through crowds of adoring supporters in Richmond, Virginia, in 1865, are portraits of two unidentified black soldiers, a private and a corporal. The images are commonplace mementos from the war. Soldiers white and black would fill photography studios to get their pictures taken in order to have something to give to family left behind. The loved ones, “could only wait and hope for their soldier’s safe return.”

The now anonymous pair look brave, exchanging a steady gaze with the viewer. But they were not simply contemplating an uncertain fate of life or death, a soldier’s safe return. Instead, they stared down the uncertainty of life as it had been and life as it might be.

”Bound For Freedom’s Light: African Americans and The Civil War” is on view through March 2, 2014 at the National Portrait Gallery.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)