There’s a Bunch of Animals at the Zoo this Summer Made Out of Ocean Garbage

Delightfully whimsical, the sculptures drive home the message that there’s a whole lot of trash washing ashore

Standing beside her several-times-life-sized sculpture “Sebastian James the Puffin,” one of 17 of her works installed at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo, Angela Pozzi talked about the puffin’s namesake. She created the work the same year her father James died. “He’s very dignified like my dad,” Pozzi says of the puffin, who stands on a base of just the sort of entangled fishing gear that claims the lives of many ocean birds. The birds also often fatally mistake plastic trash for food, a label beside the sculpture notes.

As she discussed the work, made completely out of trash that she and her team retrieved from West Coast beaches, Pozzi spotted litter on the ground nearby. She didn’t lose her train of thought as she reached for the discarded food tray and pitched it in an adjacent recycling bin.

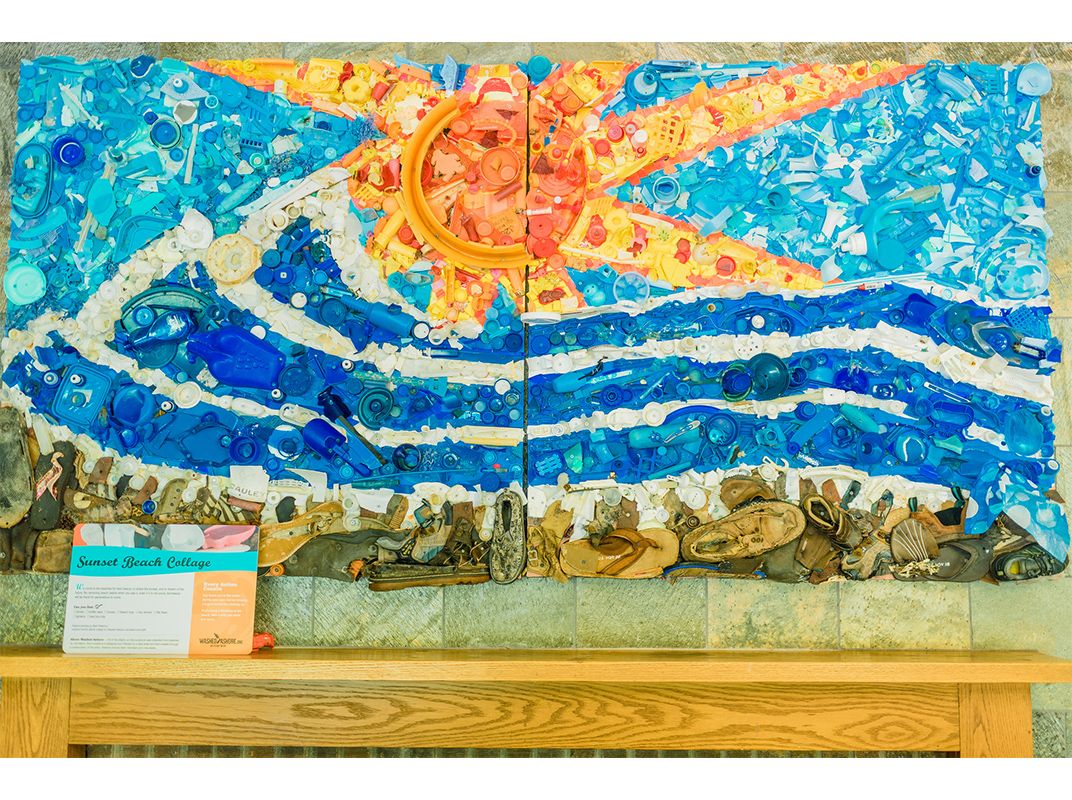

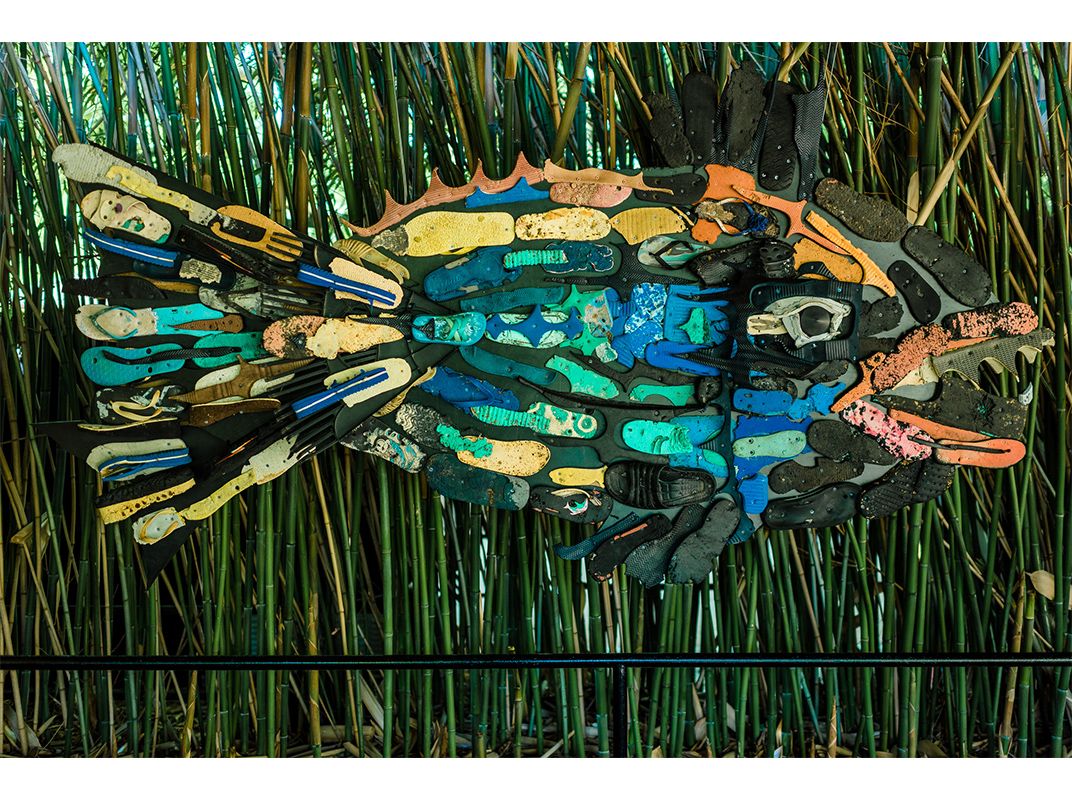

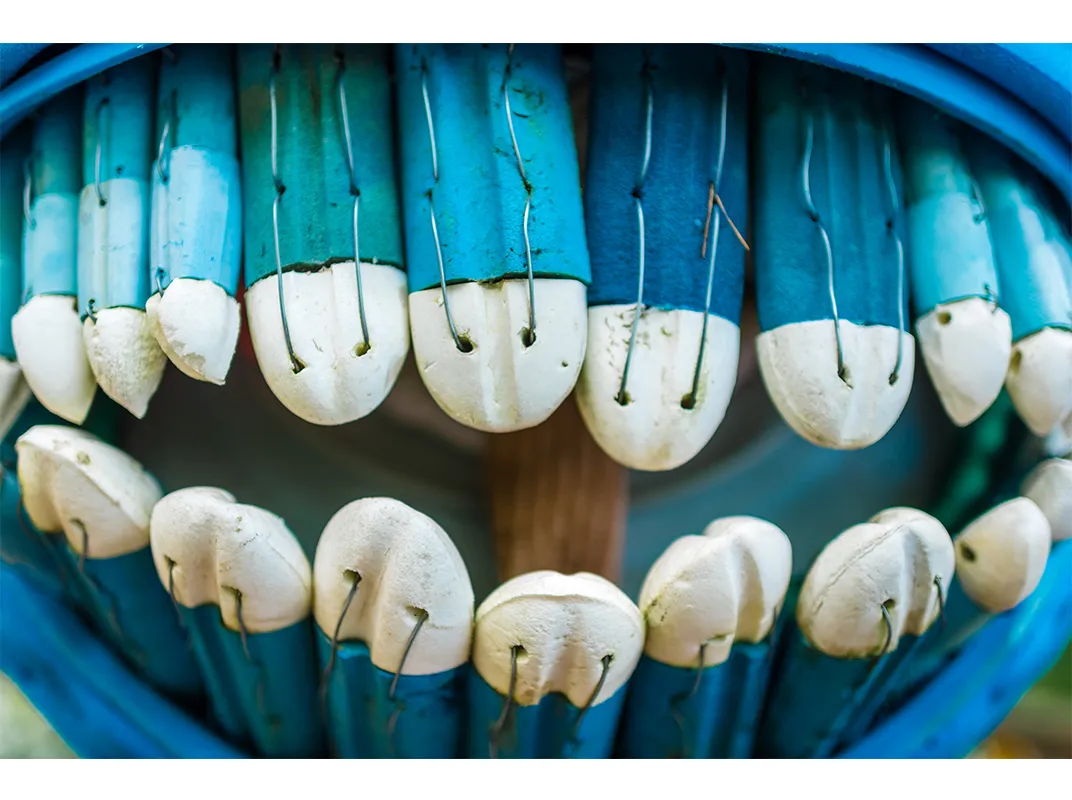

In Pozzi’s sculptures, viewers can make out everything from flip-flops, toothbrushes and eyeglasses, to microwaves, pails and shovels, and car keys. The works have their feet firmly planted in both environmental activism and the art world. Louise Nevelson, a sculptor who created artworks from discarded New York trash, is an inspiration for Pozzi, whose parents were both artists. She also owns prints by two other favorite artists, Dr. Seuss and Alexander Calder. Like the two, Pozzi creates art that is both serious and playful.

“It has to be good art, or else it won’t do the message,” she says on a tour of the works a few days before the exhibition “Washed Ashore: Art to Save The Sea” opened at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington, D.C. The works are on view until September 5.

Despite the nature of the materials, Pozzi and her team at the Washed Ashore project, achieve a remarkable and convincing array of textures. The feathers suggested around the puffin’s eyes and on his chest lend him not only that distinguished look—think of some of the drawings of Wol from “Winnie the Pooh”—but also an astonishing naturalism.

In a prior installation at Connecticut’s Mystic Aquarium of a whalebone rib cage, made also of retrieved litter, Pozzi lobbied to have the work placed on a walkway near the beluga whales. She and her team had to install the work at night.

“These beautiful, blue whales just kept looking up at us like, ‘What are you doing? What’s that about?’” she says. “We were like, ‘This is to help you.’”

Looking back, she sees a logical progression from her childhood to the art she makes today. “Ever since I was a small child, I would get excited about when the toothpaste started getting empty,” she says, “because I would get to have the toothpaste lid on top and turn it into a little cup for my trolls. I’ve always looked at repurposing supplies.”

She didn’t think of the repurposing then in environmental terms, but today, she says standing in front of a fish she made of plastics that all have bite marks on them, scientists applaud her work for its ability to raise awareness in a way that they can’t. “I need to reach inside of people,” she says. That doesn’t mean doing away with scientific facts, “but you have to grab them, and you have to make them care and you have to get their attention,” she says.

On the scientific side, the scope of the problem is enormous. The exhibition reflects on the more than 315 billion pounds of plastics littering oceans, according to a Zoo release. The announcement refers to the pollution as “the ocean’s deadliest predator—trash.”

Mary Hagedorn, a Smithsonian marine biologist and senior research scientist at the Zoo’s Conservation Biology Institute, is using fertility clinic techniques used for humans to save coral reefs. “We created the first bank for coral sperm,” she says. (A large sculpted “bleached” coral reef—or a reef on the verge of starvation—made of styrofoam on bamboo skewers, appears in the exhibit.)

“Our climate is changing, and coral reefs are very sensitive to those changes, unless we can do something about how we use fossil fuels, it will continue to happen,” Hagedorn says, noting that many people don’t understand what coral reefs are, and why they are so important.

Not only are coral reefs some of the oldest and most beautiful animals on the planet—and they are animals, rather than plants or rocks, as some might assume—but they shoulder a disproportionate, Atlas-like burden given their size. “They are these eco-dynamos,” Hagedorn says. “One quarter of all animals that live in the ocean live on a coral reef at some point in their lives.”

Corals, she adds, are almost like apartment houses. “They really provide living spaces for both large and small fish.” They also protect human homes. Hagedorn lives on the eastern shore of Oahu, where a barrier reef protects her home, and those of other residents, from tsunamis. “Honolulu is at risk of a tsunami, because it does not have a barrier reef,” she said.

Coral reefs, which are being threatened globally by surging ocean temperatures, are not only animals, but they are habitats. Hermaphrodites, they reproduce both sexually and asexually. “They are very complicated biologically,” Hagedorn says, noting that coral reefs have some of the most restrictive reproductive schedules of any animals. The vast majority of coral species only reproduce once a year, for two to three days, and just 45 minutes each of those days. “Even pandas have a longer season that they are sexually active,” she says. If coral stays bleached too long, it can throw off an already delicately-balanced reproductive process.

In coral, which Hagedorn says already contributes $350 billion a year to the global economy, she sees promise in the “kind of chemical warfare” that the species use to fight one another as they compete for light (as trees do). “These antimicrobials are going to be really important in terms of our future pharmaceutical actions,” she said. “They’re a lot more than just a pretty face.”

For Pozzi, the pretty faces of at-risk ocean life are made of objects that were irresponsibly discarded precisely because they were thought to have outlived their usefulness. In her sculptures, however, they experience a Kafka-esque transformation. And she just sees the scale of her project growing and growing. (Mike Rowe, of “Dirty Jobs” and “Somebody’s Gotta Do It” fame, spent an hour with the Washed Ashore team recently for a show. “He goofs around and he’s silly, but he was really serious with us,” Pozzi says, noting that Rowe picked a boot for the penguin sculpture’s bottom.)

“I’ve always thought that this should be a global project,” she said. “We’ve created in six years 66 sculptures out of about 18 tons of garbage that just came ashore in a 300 mile stretch. And it’s only just a few people picking it up. What if we got people around the world picking up garbage?”

Washed Ashore: Art to Save the Sea is on view at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo in Washington, D.C., through September 5, 2016.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/86/a8/86a89ff3-907e-4467-8d5d-32976fec3044/27249738695_f22046b9a4_k-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mw_by_vicki.jpg)