When the Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist Brian Lanker was a young teen in the 1960s, he watched images flashing across his television screen of police officers attacking civil rights activists with dogs, clubs and fire hoses.

As Lanker grew up and graduated from college, he would gradually come to a realization that would guide his photography until his death: everyone deserves respect. His camera would not only record visual information, but also be a probe, revealing the inner essence of the individual.

During Lanker’s tenure in the early 1970s at the Topeka Capital-Journal, he was twice named Newspaper Photographer of the Year, and in 1973, when he was just 26 years old, he received a Pulitzer Prize for his series on natural childbirth—photographs that were, according to one of his editors, “all about explaining life.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/00/e9/00e9009d-70d2-454a-84df-98ed8f17c2c5/npg_19_333_4-angelou_ext.jpg)

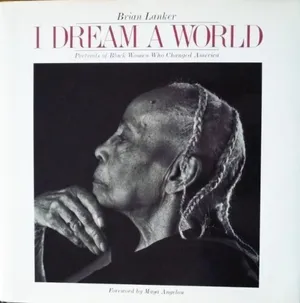

I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America

The 75 photographs (and interviews) by Brian Lanker were exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The book can function as art, history, literature or social commentary.

Lanker published his first collection of photographs and essays, I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America, in 1989, in collaboration with the poet and civil rights icon Maya Angelou and garnered instant acclaim. Lanker’s 75 the elegant and indelible portraits of women like Rosa Parks, Leontyne Price, Alice Walker, Angela Davis, Angelou, and other Black writers, entertainers, athletes and political leaders. “In this book we meet them,” Angelou wrote in the foreword, “undeniable strong, unapologetically direct.”

“I Dream a World,” Jewell Jackson McCabe, president of the National Coalition of Black Women, told the Seattle Times in 1991, “is the strongest civil-rights statement about Afro-American women in the past 50 years. It is a monumental document that will live beyond this generation and into the 21st century.”

Following the book’s publication, an exhibition of Lanker’s portraits, organized that year by Washington, D.C.’s now-defunct Corcoran Gallery of Art, drew a record crowd with 11,500 visitors arriving to view the photos at the show’s opening.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c0/11/c0114071-a2a1-406f-8743-83f0ebe7b0b0/npg_19_333_41-jordan_ext.jpg)

Lanker, who is white, attributed his work to what he called “my own growing awareness of the vast contribution Black women have made to this country and society, a contribution that still seems to have gone largely unnoticed,” he wrote. “As a photojournalist, I felt the need to prevent these historical lives from being forgotten.”

Now more than three decades later, the exhibition returns in part to Washington D.C., “I Dream a World: Selections from Brian Lanker’s Portraits of Remarkable Black Women” is on view at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in two showings; part I, now through January. 29, 2023, and part II, from February 10 through September 10, 2023. The book’s contents, according to the organizers, “have never seemed more relevant.”

“The photos are the result of a warm exchange between the photographer and the sitter. It’s certainly been a collaborative effort to create these pictures,” says Ann Shumard, the museum’s senior curator of photographs and the show’s coorganizer. “They’re humane, they’re sympathetic, they’re respectful and really affectionate portraits of these women that Lanker greatly admired.”

Lanker had a reputation for leaving nothing to chance. One critic labeled him “pertinacious” by nature. His idea to record the history of Black female changemakers took hold when he first heard Barbara Jordan’s speech to the 1976 Democratic National Convention and grew after he’d read Alice Walker’s The Color Purple. His subjects, he determined, needed to be uplifted as role models for all to see. An initial list of 25 candidates quickly expanded. He spent hours conducting interviews for his essays that he paired in the book with the portraits. Of the more than 70 people Lanker reached out to, only two—singers Ella Fitzgerald and Aretha Franklin—would be unable to participate for reasons outside of their control, says Shumard.

“Though I wanted to come into these women’s lives, I was not sure they would care to open their worlds and sometimes fragile pasts to me,” Lanker wrote. “I was pleased and surprised that not once in the course of two years of work was I ever left feeling alienated or distant because of my race and gender.”

When Lanker traveled with his family to New Orleans to photograph Leah Chase, the “Queen of Creole Cuisine,” she brought out pretty much every single dish on the menu, says Shumard. Lanker’s family staggered away from the restaurant with bellies full of cheese grits.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6a/fc/6afcede5-8e79-43b3-95c0-15d76d9273c2/npg_19_333_52-parks_ext.jpg)

Lanker knew from the start that the project would not be a showcase for himself as a photographer. Instead, each portrait would fit the individual, not the frame. He chose black-and-white film. His compositions invoked memory, wrote the Seattle Times, a sense that these women existed in history, not just as pictures on a wall.

“A photograph can only record a particular moment, and it’s subjective,” says Shumard. “There will always be mystery. And I think that’s true with these photographs. “

When Lanker reached out to the pioneering community organizer and educator Septimus Poinsette Clark, he found out that “the Mother of the Movement” had recently had a stroke, and likely unable to participate in the project. Rather than give up on the woman he felt embodied the spirit of the project, Lanker spent three days in a motel room waiting to meet the 89-year-old Clark. After talking to her, the photo’s composition came to him in mere minutes. In order to hide the side of her face that was paralyzed, he had her sit in profile for the few minutes she could sit proudly and comfortably without oxygen. The photograph now graces the book’s cover, and is the main portrait for the exhibition.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3d/1c/3d1cef01-acd2-4816-8f2e-2acb7b117cb6/npg_19_333_54-price_ext.jpg)

“How do you take someone in a nursing home, in a wheelchair and on oxygen, and give her the dignity and the strength her life embodied? It transcends the reality of the circumstances I had to work with,” Lanker later said.

Rosa Parks, for instance, is one of the women defined by circumstances, says Shumard. Besides her role in the Montgomery bus boycotts, the rest of Parks’ life story is relatively unknown. Lanker photographed Parks as a much older individual, someone who had weathered years of death threats and hostility. The photo captures her “still standing, erect and with great dignity,” says Shumard, “but in a different phase of her life.”

“We’re choosing pictures that visitors are going to be drawn to,” says Shumard, “If someone really wants to dig in, they can do it in one pass, but they may very well pinball through that space, and just go to the ones that appeal to them. And that's fine… The goal is to make the work accessible so that someone feels invited.”

“This celebration of sisters is not an attempt to elevate or lower any segment of society,” Lanker wrote in the book’s prologue, “It is merely an opportunity to savor the triumphs of the human spirit, a spirit that does not speak only of black history. My greatest lesson was that this is my history, this is American history.”

Shortly before Lanker died of pancreatic cancer in 2011, he whispered to a colleague, “There’s just so much left to do.”

“I Dream a World: Selections from Brian Lanker’s Portraits of Remarkable Black Women” is on view at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in two showings; part I now through January. 29, 2023, and part II from February 10 through September 10, 2023. The exhibition is co-curated by Ann Shumard, the museum’s senior curator of photographs and Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, the museum’s former senior historian and director of history, research and scholarly programs.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1500x1500:1501x1501)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/dd/11/dd11d219-3348-4688-9c70-045699bb4a92/npg_19_333_16-clark_ext.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f9/31/f931cdab-b50b-428c-a50b-85c0346f6644/npg_19_333_30-gibson.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/79/61/796106cc-3a61-41aa-80b2-594863785a64/npg_19_333_35-horne_ext.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2a/45/2a45881d-db8d-42f8-a356-0c9be416a478/npg_19_333_51-odetta.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/27/09/27096014-99b3-4619-99d1-ade0a54a07a4/npg_19_333_57_rudolph_ext.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ee/17/ee17cf5b-dc25-403d-a4f4-e44e7add2ef5/npg_19_333_68-tyson_ext.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4e/0d/4e0ddc7d-26af-4b22-bcce-db0ce490a655/npg_19_333_71-walker_ext.jpg)